People often ask me what the 'best' Roman history movie of all time is, and the problem with answering this question is that 'best' is, obviously, entirely subjective. Perhaps we should replace 'best' with 'most accurate', but the problem with this approach is that, well, it's a movie, right? All historical movies have to dance a fine line between historical accuracy and visual razzmatazz, which is why they are often filled with such visual fuzz as burning arrows. As a keen archer, I have fired burning arrows and believe me when I tell you that the only thing likely to be singed by a burning arrow is your own hand. But, flying through a gloomy sky at some angry people, they are visually engaging, and so directors love to throw them in, and the historical accuracy be hanged.

In general terms, weighing up the historical accuracy as the prime modifier, the 'best' Roman history movie is Monty Python's Life of Brian, which might come as something of a surprise to most people, but as someone who has spent the past two decades lecturing in Roman history, it is the only historical movie which I have ever used to give examples of how the ancient world worked.

The 'Romanes eunt domus' scene from Life of Brian is a very good way of demonstrating the relationship with the Latin language held by people in the provinces for whom Latin was not a first language. It's safe to say that this includes the majority of the population of the empire. Latin was the language of power across the Roman world, even in the majority of Hellenic eastern parts, and the only way to effectively wield such power was through the medium of Latin. It's one of the reasons why the Catholic Church uses, to this day, Latin as its own demonstration of power over its adherents and one of the reasons they started setting fire to people when they proposed translating Bibles into languages other than Latin. It might have been dressed up as 'heresy', but the real challenge to the status quo was in democratising the language that power could be divested by.

In post-Roman Britain, for example, the people who operated at the very top of society, and so for whom Latin was the language of power, had all either been tossed out on their ear or had left to go and curry favour with an unhappy Honorius. The ones who were left didn't really speak Latin as a first language and, instead, probably spoke the language we call Brittonic. As they filled the power vacuum, however, they were still aware that the best way of demonstrating that it was they who now held power was to do so via the medium of Latin. If you didn't speak Latin, you weren't 'king'.

The trouble with this is that once that rice-paper thin veneer of Latin-speaking 'Roman' bureaucracy had headed off towards Gaul, there were far fewer people around who had a fully working grasp of what was, and remains a very complicated language. Something beautifully demonstrated by Life of Brian.

There are plenty of examples of epigraphy from post-Roman Britain in which the local warlords have thrown up markers and gravestones written in what was, to be plain, rather terrible Latin. They knew that they should be using it to demonstrate their power, but nobody was around to twist their ear, tell them they had conjugated the verbs incorrectly, and then make them write it out a thousand times across the walls of the city.

Romans go to the house!?

The other problem with engaging with popular depictions of Roman history is that I find myself tutting and sighing at the slightest discrepancy, a character fault that I am normally able to keep a lid on in all but the most egregious of indiscretions. The long-suffering Mrs Coverley, who, to be fair, I met via the medium of Roman history, has become used to me hitting pause, pointing at the screen in mock outrage, and spluttering about how that is absolutely incorrect. I don't usually do it in polite company, mostly because I don't keep polite company.

One such moment happened the other day when a depiction of a Roman banquet showed the feasters lolling about on beds, cheek to jowl, scattered about like cushions in student's bedsit. The impropriety of this slovenliness would have scandalised the guests had this been an actual Roman feast. All this goes to propose the question - 'Did the Romans Eat in Bed?'

The Romans didn't so much eat in bed as eat whilst lying on a bed. The 'bed' in question, the lectus, could be found in the Roman bedroom, the cubilarium, or in the triclinium, the dining room. More correctly, the lectus was the bedstead or the base on which was laid a torus, a form of mattress that would be filled with a variety of materials to match the splendour of its owner. Some were filled with swan down, others with straw. Whilst the lectus in a bedroom might take a form that would be instantly recognisable as a bed to modern eyes, those found in the dining room might just be formed from concrete or stone bases.

The triclinium was oblong in shape, and according to Vitruvius (VI.3 8) was twice as long as it was broad. The same author (VI. 10) describes triclinia to be used in summer, which were open towards the north and looked over a garden.

As the word suggests, each triclinium consisted of three beds arranged around a central table. It was on these beds that the guests would gather for the accubatio or the act of reclining during a meal.

During a formal banquet, they were called triclinia strata (Caes. B. C. III.92), and they were all arranged so as to be of equal dimensions and in decoration. No one bed was larger than the others, nor was one more luxuriously appointed than any other (Varro, L. L. IX.47).

During the meal, each guest would lean upon his left elbow, leaving his right arm free to eat with. As two or more lay on the same couch, the head of one man was near the breast of the man who lay behind him, and he was therefore said to lie in the bosom of the other (Plin. Epist. IV.22).

For Roman feasts, each lectus would hold three guests, meaning that the ideal number of guests at a dinner party was nine. Varro (Gellius XIII.11) suggested that the number of guests ought to be nine so as not to be less than that of the Graces nor to exceed that of the Muses.

The couches were always elevated above the level of the table, which would allow each man to lay flat upon his chest and stretch out a hand towards the table in order to feed himself. Once he had taken his food, he would turn back onto his left side, leaning on his elbow. Horace alludes to feeling sated with turning in order to repose upon an elbow (Sat. II.4.39), in the same way as we might lean back and rub a particularly full belly in modern terms.

The people at the feast wouldn't simply lay where they liked, and each position could be expressed in terms of supra and infra - above and below. As explained by Livy (Liv. XXXIX.43), each person was considered as below him to whose breast his own head approached. If you rested on your left elbow and there was someone behind you, you were below them in the pecking order.

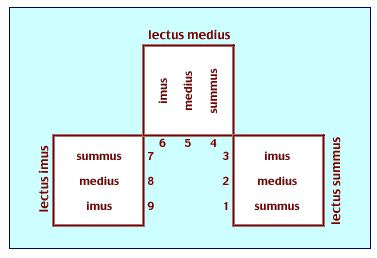

You can then work out in your imagination (or use the diagram below) that if you have three beds with three people on each bed, laying on their left elbow, then, seen from above, with the central bed at the top, the person who is lying on the right-hand bed, at the very 'bottom' of that bed is person number one and the order goes counter-clockwise all the way to number nine.

Thus, the host, or the most important guest, such as the emperor, would recline at one. But that doesn't necessarily mean that the order was from most important to least important. Number four on the seating plan was also seen as a prime seat, and guests who had something to celebrate, such as a birthday, even if the birthday was held in their honour, might recline in this position. Number eight was the position held by the person responsible for organising the feast, who might be the householder if they were different from the host or the owner of the slaves who attended the meal. It was considered that eight was a prime position from which to issue orders and oversee the attendants. Unless there was an exception for position number four, the central position on the bed was considered to be the most honourable (Virg. Aen. I.698).

Whilst number eight was the 'master of the feast,' the actual running of the slaves, the timing of the delivery of meals, and the general overseeing of the whole banquet were entrusted to a specialist slave called tricliniarcha, who, acting like an Edwardian butler, ensured that everything proceeded in good order.

References and Further Reading:

Caesar, G. J. (2021). The Civil War (J. M. Carter, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Gellius, A. (2004). Attic Nights (J. C. Rolfe, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Horace. (2005). Satires and Epistles (N. Rudd, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Livy. (2006). The History of Rome (B. Radice, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Pliny the Younger. (2003). Letters (B. Radice, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Varro, M. T. (1996). On the Latin Language (R. G. Kent, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Vergil. (2008). The Aeneid (R. Fagles, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Vitruvius. (2009). On Architecture (R. Tavernor, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

If you enjoyed this article, you’ll love my latest book, Black Magic Baby, crammed full of interesting answers to all the questions you ever had about Roman history that will keep you turning pages long into the night. They make rather cool gifts for nerdy types who go mad for that sort of thing!

Print or ebook versions are available at the link below!

"Brian" owes much of its accuracy to Terry Jones studying history at Oxford and figuring out how to make it funny with Michael Palin.