Although the Roman Empire saw a huge increase in the number of schools, there was nothing that resembled a system of free public education. Formal education was only available to the children of those who could afford it. The initiative to create basic schools was left in the hands of localities and the parents who could pay. Institutions of higher learning flourished in major urban centres, with Athens holding the top spot as the Roman world's most eminent university city. But the emperors very quickly adopted the role of patrons of learning and education, granting privileges and sometimes even financial aid to practitioners of the learned professions. The first such salaried 'professorship' was Quintillian, perhaps the most famous of the Roman rhetoricians, who, under Vespasian, was appointed the chair of literature and rhetoric and whose pupils included the younger Pliny and almost certainly Tacitus. Other such positions, at Rome, Athens and elsewhere, were started by subsequent emperors. Over time, this patronage led the emperors to intervene more often in educational matters and by the end of the third century, nearly all the schools of the empire were under some sort of imperial influence.

The curriculum of Roman schools continued its traditional emphasis on grammar, rhetoric, literature, and philosophy, with oratory being the jewel in the crown and, above all, the peak of Roman education. But since the importance of political oratory in Roman public life dwindled as the senate became increasingly irrelevant as anything other than a glorified talking shop, the law courts became the only practical outlet for oratorical skill, and the training in schools degenerated into a series of rather meaningless rhetorical and philosophical exercises. Thinking for the sake of thinking. Attention instead became fixed on style instead of content, the goal being artificial, showy, epigrammatic grandstanding developed through a series of classroom-based recitation exercises. All trousers and no sausage, as we used to say back in the day. There were declamationes, or set pieces; suasoriae, chin-stroking speeches about nothing in particular, such as fantastical themes or self-persuasive introspection; and controversiae, debates on fictitious and sometimes bizarrely contrived legal matters.

But all this beard-twirling nonsense is one thing and, perhaps, the sort of thing one would expect a bunch of rich playboys with too much time on their hands and a huge sense of their own self-importance to engage in. But what was the basic Roman education system like? What did the kids learn?

In any historical investigation of education in ancient Rome, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by the term "school." The Latin term schola could refer to many things — from a place of rhetorical instruction to a military training area or philosophical discussion hall. In this essay, the term “school” will be used in a modern sense: a physical or institutional setting primarily for educating young children in the basic skills of reading (lectio), writing (scriptura), and arithmetic (calculi), typically under the guidance of an instructor (ludimagister or grammaticus), and often attended by multiple pupils. This definition excludes elite institutions of higher learning and adult education centres, which were more philosophical or rhetorical in nature, such as those attended by Cicero or Seneca in their youth.

The Roman education system, such as it was, lacked uniformity and state regulation. No empire-wide educational standard existed, nor was there a formal curriculum imposed by any Roman authority. Nevertheless, a system of schooling, as defined above, did exist. We know this through literary references, inscriptions, and, crucially, archaeological remains from across the empire. Children were educated in structured ways — sometimes at home, sometimes in hired rooms or semi-public spaces — and a class of professional educators did emerge to serve this need.

The sources that inform us about Roman schooling are largely literary and elite in nature, including works by Quintilian, Pliny the Younger, Martial, and Suetonius. However, archaeological finds — such as writing tablets, wax styluses, and graffiti from Pompeii — provide crucial insights into how and where these educational practices occurred. Epigraphic evidence also records the presence of teachers and their pupils in various parts of the empire, helping to map the geographic and social extent of schooling.

Access to education in ancient Rome was influenced by an interplay of class, gender, social expectation, and regional variation. Although literacy and basic numeracy were highly valued in Roman society, they were not universally accessible. Education for children was, in practice, a privilege of the wealthier classes, although not entirely exclusive to them.

The sons of elite families were commonly educated, as evidenced by numerous autobiographical references from Roman authors. Cicero, writing in the 1st century BC, mentions in Brutus that he was educated first by his father and then by various teachers of grammar and rhetoric. Quintilian, too, refers to the expectation that sons of senators and equites would receive a structured education (Institutio Oratoria, I.1.6–11).

However, these were individuals from privileged backgrounds. There is comparatively less literary evidence for the education of poor children, and that absence itself is informative.

Girls were less commonly educated, though not categorically excluded. Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi, is often cited as an example of an educated Roman woman, and inscriptions such as CIL VI.9719, commemorating a woman named Claudia Severa, suggest that literacy among elite women was not unknown. The Vindolanda tablets from northern Britain include a birthday invitation written by Claudia Severa, indicating female literacy in frontier regions of the empire (Tab. Vindol. II.291).

The education of slave children is a more ambiguous topic. Some slaves were trained in literacy, particularly if they were destined to become secretaries, accountants, or tutors within wealthy households. The poet Horace, the son of a freedman, was famously educated in Rome and then Athens, suggesting upward mobility was possible, albeit rarely.

There is no direct mention of state-owned schools for the poor or universal access to education in Roman sources. Martial, in Epigrams 9.68, describes poor boys attending schools that were little more than rented rooms, but even this required some fee and often the sacrifice of labour that could be used elsewhere. Education for the urban poor would have been irregular, if available at all.

Thus, while primary education was broadly valued, it was neither universal nor free from social constraints. Most children who attended school were male, urban, and from families with the financial means to support non-productive activity.

The Roman primary curriculum focused on three core areas: reading, writing, and arithmetic. This was known as the domain of the ludus litterarius, overseen by the ludimagister. The emphasis was on memorisation, imitation, and repetition, and pupils were expected to master both Latin language structure and basic calculation skills.

Reading began with the alphabet. Quintilian notes the importance of not overwhelming the child with poor habits from early on, emphasising a gradual process (Institutio Oratoria, I.1.24–36). Pupils were introduced to syllables and then words, often drawn from literary examples. Once reading was established, writing followed, typically with stylus and wax tablet before progressing to ink and papyrus. Martial refers humorously to the wax tablets used by pupils in Epigrams 14.188, indicating their ubiquity.

The teaching of arithmetic likely included the use of counting boards (abaci) and pebbles (calculi). Calculations involved basic operations and may have extended to commercial mathematics for boys destined to become merchants or accountants. A 3rd-century AD graffito from Pompeii includes a multiplication table scratched into a wall (CIL IV.5296), indicating that rote learning was a critical part of numeracy instruction.

In some schools, pupils would go on to study grammar and literature with a grammaticus, who introduced them to works by authors such as Virgil, Homer, and Ennius. However, this was typically secondary education and went beyond the ludus litterarius stage. Suetonius, in De Grammaticis, provides biographical sketches of notable grammarians and their role in the educational chain.

There is little direct archaeological evidence for classroom texts, but writing tablets found at Vindolanda, and others from Londinium, suggest pupils wrote dictations, letters, and lists. These were likely copied from models given by the teacher. Wax tablets from Egypt, including examples preserved at Tebtunis, offer similar insight into pedagogical repetition and the stylised formats of instruction.

While modern curricula favour conceptual understanding, Roman primary education was mechanical and memorisation-heavy. The goal was functional literacy and practical numeracy — a foundation for higher learning, if such a path were available.

Archaeological and epigraphic evidence for Roman schools remains limited but significant. Schools were rarely purpose-built structures; instead, they were often informal spaces — rooms in a house, parts of public buildings, or even porticoes and colonnades. The lack of architectural distinction complicates identification, but inscriptions and artefacts help reconstruct their existence.

One of the most illustrative examples comes from Pompeii. A series of graffiti, especially from the insulae near the Forum, record lines of copied texts, spelling exercises, and even pupil complaints. In CIL IV.8075, one child writes “Amo te” repeatedly, perhaps as a writing practice. Another graffito, CIL IV.10039, may show the use of syllabic exercises or verses. These markings appear in semi-public areas, suggesting that some schooling occurred outdoors or in shared spaces.

At Herculaneum, the so-called “College of the Augustales” has been posited as a possible school location, although this remains speculative. More promising are the Egyptian papyri and wax tablets found at Oxyrhynchus and Tebtunis, which preserve pupil writing exercises dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. These documents, written in both Latin and Greek, show not only instructional texts but evidence of corrections, classroom routines, and bilingual instruction.

Epigraphic sources often identify educators by profession. In CIL VI.9203, from Rome, a teacher named Lucius Orbilius Pupillus — later mocked by Horace — is commemorated. Other inscriptions label deceased individuals as grammaticus or ludimagister, confirming both their existence and status in society.

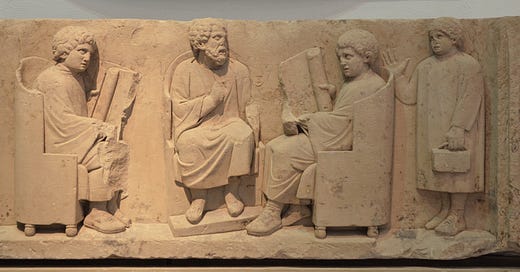

A particularly notable find is a relief from Neumagen (modern-day Germany), now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier (main picture). This funerary monument depicts a seated teacher with a group of students holding wax tablets, offering visual confirmation of the classroom arrangement and didactic tools (RLM Trier Inv. Nr. 2384).

Thus, while physical buildings identified conclusively as “schools” are rare, the combined archaeological, epigraphic, and literary evidence demonstrates that educational spaces were widespread, informal, and embedded within the fabric of Roman urban life.

The ludimagister, or primary schoolteacher, was the cornerstone of Roman basic education. Unlike the grammaticus or rhetor, whose students were older and more advanced, the ludimagister taught the fundamentals. His position was modest — both socially and financially.

Roman sources rarely idealise primary teachers. Horace, in Satires I.6.71–75, recalls being flogged by his teacher Orbilius, whom he nicknames plagosus (the beater). Suetonius confirms this teacher’s strictness in De Grammaticis (4), highlighting the rough discipline common in schools. Corporal punishment was not merely tolerated but expected as a disciplinary tool.

Teachers often worked independently, renting a space and advertising their services. Quintilian disapproves of sending boys to poor teachers due to their lack of moral example (Institutio Oratoria, I.2.4), implying a market-driven competition for pupils. Pupils brought their own materials: wax tablets, styluses, and inkwells. Instruction was largely oral, with pupils copying examples, repeating texts aloud, and reciting from memory.

The classroom routine, according to literary and archaeological records, started at dawn and continued into the afternoon, six days a week. Martial quips about the noise made by children reciting and the nuisance caused to nearby residents (Epigrams 9.68), which further confirms the often-public or semi-public setting of instruction.

Pay was meagre. Teachers depended on fees paid directly by parents. In his Epistles (1.20.42), Horace contrasts the wealth of merchants with the poverty of grammarians, reflecting a societal undervaluing of educators despite their civic utility.

Yet the teacher’s authority within the classroom was considerable. He controlled access to knowledge, enforced discipline, and set the tempo of instruction. While not revered like philosophers, the ludimagister was a recognised figure across the empire, as attested by inscriptions bearing that title from Gaul, North Africa, and the eastern provinces.

Roman schools, despite their relatively informal nature, played a crucial role in the social and political fabric of Roman life. They were integral to the development of Roman citizenship, fostering the skills necessary for participation in both public and private spheres. Education was not just a private or familial pursuit; it was also a civic obligation in the context of the wider empire.

Children who received schooling, particularly in urban centres, were equipped to engage in legal and commercial transactions, social relations, and civic duties. Literacy in Latin was essential for navigating legal, religious, and economic systems. Wealthier families ensured that their children were prepared for participation in the public sphere — including in government and the military — by mastering reading, writing, and oratory.

Indeed, education was particularly valued by Roman elites as a preparation for rhetorical training and political life. Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria serves as both an instructional guide and a reflection on the educational ideals of the period. He makes it clear that education, from the primary level up, was meant to cultivate citizens who could participate in Roman politics, law, and military service (Institutio Oratoria, 1.1). For children in the ludus, the skills developed were not simply academic but directly aligned with the civic virtues expected of Roman citizens.

However, the function of Roman schools was not confined solely to the production of capable orators and politicians. Schools, as places of instruction, also served as social hubs where status and class distinctions were reinforced. The differentiation between the instruction of the elite and the poor, and the presence of gendered disparities in educational access, reflect the deeply hierarchical nature of Roman society. The availability of education to the elite served to maintain existing power structures, while the exclusion of lower-class children from formal education ensured that the majority of the population remained outside the decision-making processes of the state.

For the Roman elite, education was as much about perpetuating social status as it was about acquiring knowledge. The ludus and grammatica functioned as preparatory stages for higher education, which would take place under the tutelage of a rhetor (rhetoric teacher) and in later life, in the courtroom or Senate. For the common people, however, education was more functional, equipping them with the skills needed to read contracts, keep accounts, and engage in the basic practices of commerce and law. While this education had more limited reach, it played a key role in sustaining Roman economic and civic structures.

In his Institutes of Oratory, Quintiliian has a passage that perhaps nails the whole issue of the education of children, not only in Roman times but in modern ones, too. We often treat schools as places we send kids off to be educated in and that might seem like a bloody obvious statement, but as someone who has worked in education, although not with young children, schools have always seemed to me to be places that are less about direct education and more about instilling the magic of learning in children. All children are perfectly capable of learning anything at all, if inspired to do so, and schools should, in my humble opinion, be places where their imaginations are fired and their innate love of discovery nurtured. If a child is interested in history, fill their excitable little mind with kings and swords, myths and dragons - there'll be plenty of time for Corn Laws and Jethro Tull (not the fun one with a flute) when they get older. Universities are for learning - schools are for learning how to learn.

But, as I said, Quintillian hit another nail on the head:

"As regards parents, I should like to see them as highly educated as possible ... and even those who have not had the fortune to receive a good education should not devote less care to their children's education but should for that very reason show all the greater diligence in other matters where they can help."

(Inst. Orat. I i.4)

References and Further Reading

CIL IV.5296. . Graffito from Pompeii. Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

CIL IV.8075. . Graffito from Pompeii. Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

CIL VI.9203. . Inscription from Rome. Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

Horace. (Satires I.6.71–75). Satires.

Martial. (9.68). Epigrams.

Pliny the Younger. (Letters 5.1, 5.3). Letters.

Quintilian. Institutio Oratoria.

Suetonius. (De Grammaticis).

Tab. Vindol. II.291. Vindolanda Tablets. The Vindolanda Trust.

Vindolanda Tablets. The Vindolanda Trust.

RLM Trier Inv. Nr. 2384. Funerary relief. Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier.

Great article - really interesting!

I suppose that within the Roman army literacy and numeracy might have been more common than within the general population, as it would have been necessary for the transmission of orders and other important information.

Thanks once again for sharing your insights about matters Roman.

This was a particularly enjoyable article: Lots of evidence, delivering a good general understanding. Plus discussion (and pictures!) of waxed tablets, which are one of my favorite things that I learned about in my years doing medieval reenactment.