In his account of the now infamous Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, Herodotus recounts how Demaratus, son of Ariston, goes about explaining Spartan pre-battle customs to Xerxes before everyone starts splattering each other.

"Tis their custom, when they are about to hazard their lives, to adorn their heads with care."

(Her. Hist. 7.209)

Although the picture below is a little grainy, it depicts a 6th Century BC Spartan warrior with a neatly trimmed beard and neat hair formed into what at first appear to be plaits. This might just be a stylistic treatment on the part of the sculptor, but it clearly shows that Spartan men took great care of their physical appearance, particularly when it came to trimming and tweaking body hair. There are parts of Plutarch in which he becomes positively giddy in stressing the physical beauty of the Spartans.

Yet, glance around at books, television and film, and the depictions of ancient Greeks range from scraggly-haired, wild-eyed, blood-soaked loons to bushy-bearded philosophical types with hair flowing like great manes.

There are some advantages of taking care of your hair before a battle that goes beyond simple vanity or course. Nobody wants to be swatting heavily away at the Persians with your hair flying about, covered in blood, and getting in your eyes. The practice of plaiting is something that can be done relatively quickly and on your own. But the better alternative would be not to have had the long hair in the first place, and the idea of the military buzzcut favoured by later soldiery types like the emperor Caracalla - more on him in a bit - is clearly not an option.

Fashions changed as much back then as they do now, but for most of the Classical Greek period, it was the norm for men to sport a full beard, either with or without a shaved top lip. Shaving was not seen as something particularly manly, at least until the time of Alexander, whose baby-smooth cheeks were clearly meant to be part of the propaganda tool that the distribution of his image became. His cherubic little face is all over the Ancient world he did so much to conquer, to the extent that, if you squint a bit, you can start to draw direct parallels between the iconography of Alexander and later figures who needed to get their faces out there to the people. Like Jesus, for example, who starts out beardless. That's a whole other topic, of course.

Exactly why Alexander went beardless isn't clear. He might just have had terrible facial hair, which looked awful when it grew? Perhaps he liked the way it made him look? On campaign, having a beard can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, with a beard, you don't have to worry about shaving in your tent every morning and on the other, if you shave, the lice have nowhere to live. But his marble-smooth chin did one thing important - it set a trend.

At first, the Romans were as fond of a good beard as the Greeks, and the transition to going beardless was, according to Pliny the Elder, attributable to a pretty exact date:

"The next agreement between nations was in the matter of shaving the beard, but with the Romans this was later. Barbers came to Rome from Sicily in the year [300 BC], according to Varro being brought there by Publius Titinius Mena; before then the Romans had been unshaved."

(Plin. Nat. Hist. 7.211)

Not only does he attribute it to a date, but the proud title of being the first Roman to shave daily goes to the second Africanus, the great general and destroyer of Carthage, Scipio Aemilianus. It should be noted, though, that Scipio died in 129 BC, so there was presumably a long period in between when those Sicilian barbers were busy but just not on the same faces every morning. The image below has been tentatively attributed to Scipio Africanus, and if it is, although he first appears to be clean-shaven, look closer, and you’ll see that his beard, although rather wispy, is still there. It is possible, then, that this daily shaving described by Pliny is not a full face scraping but regular trimming and tidying up of what might otherwise have been a scruffy old mess. Add to that his rather artfully tousled hair and this is clearly a man, whoever it is, who took some time about the way he looked.

Pliny adds, in the same passage, that ‘the deified Augustus never neglected the razor’, and he, being as influential on the face, if you'll forgive the pun, of the Roman world as Alexander was on the Greek, then sets a trend that lasts for a considerable amount of time.

The trend begins to change with Hadrian's arrival on the scene. If there are two things the Nerva-Antonine dynasty gave Roman history, it was walls and beards. Hadrian was the first emperor to be commonly shown with a beard and a myriad of coins and icons produced during his reign showed him with a changing style in facial hair over the years. He starts out with sideburns and a moustache, transforms into a fuller but well-kept beard and later in life starts to use imagery more associated with his youth, going back to having a moustache, sideburns and a free chin. At times, his facial hair resembles that of a fine Edwardian doctor than of a blood-soaked Roman emperor.

It was suggested that Hadrian grew his beard to cover up scars left by acne, but such vanity isn’t a satisfactory answer. The Roman penchant for using realistic iconography that depicted them ‘warts and all’ would tend to suggest that a few scars wouldn't be a problem, even if portraiture was a carefully managed affair. Shaving was also an important right of passage to young Roman men, with the ‘first shave’ being seen as a milestone towards full manliness. Oddly, this wasn’t done as soon as the facial hair began to grow. The time at which young men first shaved their beard was marked with a particular ceremony. It was usually in their twenty-first year, but the period varied. Caligula first shaved at twenty; Augustus at twenty-five. Nero was twenty-two when he called the Juvenalia, the Celebration of Youth, during which, he ritually shaved for the first time:

”In the gymnastic exercises, which he presented in the Septa, while they were preparing the great sacrifice of an ox, he shaved his beard for the first time, and putting it up in a casket of gold studded with pearls of great price, consecrated it to Jupiter Capitolinus.”

(Suet. Nero 12)

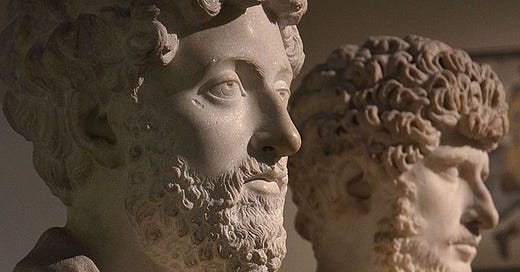

Hadrian’s love of all things Greek is traditionally given as the reason for his growing a beard, and whilst he was relatively neat, by the time we get to the great ‘philosopher king’, Marcus Aurelius, the beard has become more like that of the Greek world, fuller and more defined. Here, Marcus Aurelius (on the left) and Lucius Verus, his adoptive brother and co-emperor, are wearing their beards as very clearly defined parts of their identity. These are bold, open, in-your-face (and on-their-face) choices, not simply fashionable whims. They are beards as descriptors of character, intent and personality. By aligning themselves with the style of the philosophers, they are emphasising not only their military might and superiority but their intellectual and moral superiority, too. They are badges of office.

Within a generation or two, the beard style has changed noticeably. The emperor Caracalla was a gruff, military, soldier type who was less interested in the intellectual pursuits of his father, Septimius Severus, or of his brother, Geta, who he had murdered, and both his trim length and his haircut reflect a man who was trimmed for the battlefield rather than for the symposium.

Here, the status of his beard is setting out Caracalla as someone not to be messed around with. He is no-nonsense, clipped, efficient and curt. He doesn’t have time for all that lounging about, preening himself. Caracalla takes one bottle into the shower with him, washes, and gets out again. He has Parthians to go and kill. It seems very odd that the latest media depiction of Caracalla, in the new Gladiator II movie, should show him as being beardless when it was such an integral part of the identity of the Flavian dynasty. If we also consider that Caracalla’s father, Severus, was a Libyan and his mother a Syrian, then Caracalla and his beard must have been a striking sight, and it seems unreasonable to assume that all this wasn’t a very conscious part of the image he was trying to portray.

We can say, then, that not only were beards trimmed and preened but completely removed, and the next question is how? As we saw earlier, there were professional barbers who could do the job and Augustus was apparently attended to each morning by three of them. But for the normal person, managing a beard must have seemed like a less daunting prospect than having to perform a clean shave every morning. Roman razors could be sharp but nowhere near as precise as the ones we use today. They were usually bronze or iron with a short, sickle-shaped blade on a wooden handle. Mirrors were known but not common and were usually made from polished bronze, in which one might be able to get a rudimentary reflection. Glass mirrors existed but were expensive and relatively rare. Shaving oneself in a wobbly mirror with a cumbersome and rather blunt blade must have been such a terrible experience that those who had slaves to do the job left it up to them, and everyone else just went to see the Sicilian barbers.

Barbers operated on the streets, like the shoe-shiners of the 19th Century. You’d walk up, plonk yourself on a stool and the barber would splash your face with water, grab a towel and then set about your face with alarming alacrity. It would cost a few coins, less if you dared take on one of the apprentices. A quick rub of some sort of animal fat based salve to ease the burn and soothe the cuts and off you went again, probably no more than a minute or two later, staggering and bleeding across the cobbles.

There were other ways of removing hair, including applying pine resin, which was then ripped off, much like modern waxing, or having your skin scraped with pumice to scour out the hairs. All of this goes to show why beards became so prevalent for so long.

It is clear from the iconography that women also removed body hair, presumably by all the same means as above. Whether this was the preserve of Rome’s elite women isn’t clear as the information is too fragmented, but it’s hard to imagine that common Roman women felt it necessary to go to all that trouble.

Among men, the removal of body hair was seen as an effeminate and particularly un-Roman practice, and to do so was not only to reject the premise of masculinity wilfully but to throw out the very notion of what it meant to be a Roman. As such, we should treat the sources with a little care - they’re often written by people with agendas that are trying to smear the Roman validity of the people they are referring to.

Suetonius tells us about the grooming habits of the emperor Otho, who ruled briefly in the chaotic period after the death of Nero known as the Year of the Four Emperors (AD 69)

”The person and appearance of Otho no way corresponded to the great spirit he displayed on this occasion; for he is said to have been of low stature, splay-footed, and bandy-legged. He was, however, effeminately nice in the care of his person: the hair on his body he plucked out by the roots; and because he was somewhat bald, he wore a kind of peruke, so exactly fitted to his head, that nobody could have known it for such. He used to shave every day, and rub his face with soaked bread; the use of which he began when the down first appeared upon his chin, to prevent his having any beard.”

(Suet. Otho 12)

If you have any questions about Roman history you’d like answered, drop one in the comments, and once I have cleared the ravens from the privy and swept up the mess, I’ll get around to answering some of them!

And don’t forget to sign up for a paid subscription to get the chance to win some really cool stuff under my new giveaway scheme. Unique and exciting Roman history based goodies can be yours if you follow the link below.

Thanks for reading! If you’re stuck for a Christmas gift for a loved one, or for someone you hate, or if you have a table with a wonky leg that would benefit from the support of 341 pages of Roman History, my new book “The Compendium of Roman History” is available on Amazon or direct from IngramSpark at the link below. Please check it out by clicking the link below!

Things I never knew! Thank you for this.