Eugene Burton Ely,

October 21st, 1886

History looks at the pioneers of powered flight as gargantuans, bestriding the early decades of the 20th Century, as the Colossus of Rhodes once bestrode the harbour to the ancient Greek city. These towering, titan, pharos-like vanguards of human endeavour grabbed humanity from the bonds of the Earth and flung them, wailing like startled baby birds into the skies and then the cosmos beyond.

Me, I reckon they were all fucking idiots. I mean, brave and intrepid idiots, but fucking idiots all the same. It's one thing to climb into a bedframe powered by a lawnmower engine and launch it off a hillside; it's another to stand there and watch as the pilot saws madly at what laughably passes for the 'controls', yaws and pitches like a deranged drunk across the sky and then barely makes it down alive again, only to think "Well that looked safe. Think I'll have a go!"

I am speaking, of course, as a spineless coward, although it must be noted that I am a spineless coward who didn't die at the age of 22, concertinaed into a cornfield somewhere in France, covered in lawnmower fuel and plywood.

I am not the sort of person you would call for in a crisis unless that crisis required some sitting down and thinking about the problem over a slice of finest Somerset cheddar and a nice cup of tea. If you need someone to conceptualise the problem of putting a human into a wicker basket and then trying to pretend they are a bird, I'm your man! If it comes to getting into the basket, such things are a younger and rather stupider person's game. My name will not be sung in the halls of the heroes, nor will by name be eulogised on the scrolls of honours. But I will be at the back of the hall trying to decide if cashews go better with slices of apple and cheddar, or walnuts.

It's cashews, by the way. Walnuts are too 'woody'.

Many years ago, the Royal Navy tried to persuade young people to join their ranks by making a series of TV adverts in which they posed some questions to the potential recruit.

"Can you fry an egg?" they asked, and I thought "No." They were obviously looking to try and catch me out so they could whisk me away to a life on the waves in a ship's galley. I was too quick for them.

"Can you fry an egg on a boat?" they continued, and I thought 'No."

"Can you fry an egg on a boat in a storm?" No. No, I cannot fry an egg on a boat in a storm.

"Can you fry an egg on a boat in a storm for 100 hungry sailors?" and bless them, although they were trying very hard, I thought, "No. I cannot fry an egg, on a boat, in a storm, for 100 hungry sailors ... Perhaps you are looking for someone else? Perhaps you're looking for someone who answered 'yes' to the first question? I'm not even sure why we're having this chat, to be honest!"

"Can you fry an egg, on a boat, in a storm, for 100 hungry sailors, in the middle of a battle?"

And I thought no! I cannot fry an egg, on a boat, in a storm, for 100 hungry sailors, in the middle of a battle. If I'm honest, this doesn't seem the best time to be thinking of frying an egg at all! Perhaps some of us can put breakfast off for a few minutes whilst we man the guns to fight off the enemy!? And then it occurred to me ... wait a minute! I could probably do scrambled eggs!

I am not the man to fry your egg, nor am I the man to go on your boat. Eugene Ely, on the other hand, was not only exactly the man to fry your egg for you, but he could land his wicker basket powered by a lawnmower engine on your boat and bring the eggs with him, the mad bastard!

He was also dead by the time he was 24, of course.

Eugene Burton Ely, born on 21 October 1886 near Williamsburg, Iowa, became one of the most significant figures in the early history of aviation, particularly in naval aviation. Though he came from a relatively humble background, Ely’s contributions to aviation would have a lasting impact on both military and civilian flying.

Ely grew up in a rural environment, where his early interest in mechanics and machines blossomed. After moving to San Francisco and working as an automobile salesman, he was introduced to aviation. Ely was captivated by the potential of flight, and in 1910, he met Glenn Curtiss, the founder of the Curtiss Aeroplane Company. Curtiss’s company was one of the leading aviation companies at the time, and Ely, keen to become a pilot, quickly ingrained himself in the burgeoning aviation world.

Ely's early flight experiences were primarily as a stunt pilot, performing in airshows to promote aviation. However, his pivotal role in aviation history began when he undertook one of the most daring experiments of his time—testing the potential of aircraft for naval applications. In the early 20th century, the idea of combining aviation with naval operations was still in its infancy. However, the U.S. Navy was interested in exploring the feasibility of using planes in naval warfare, particularly for reconnaissance missions and later combat.

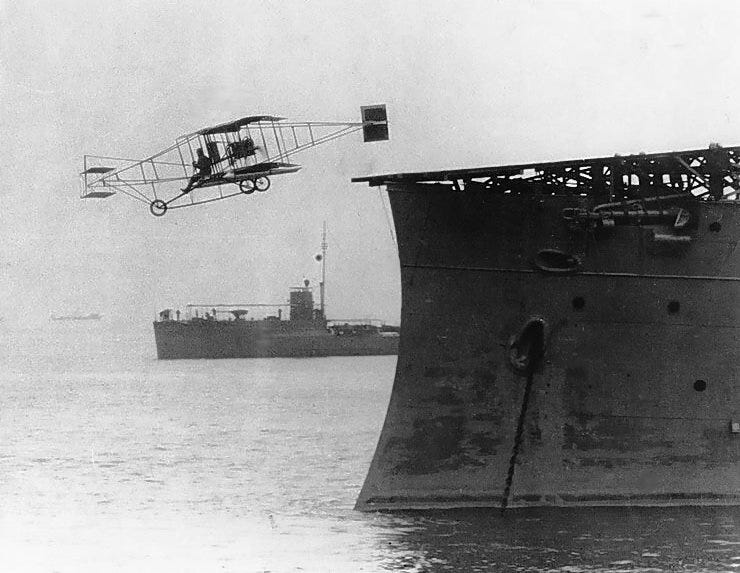

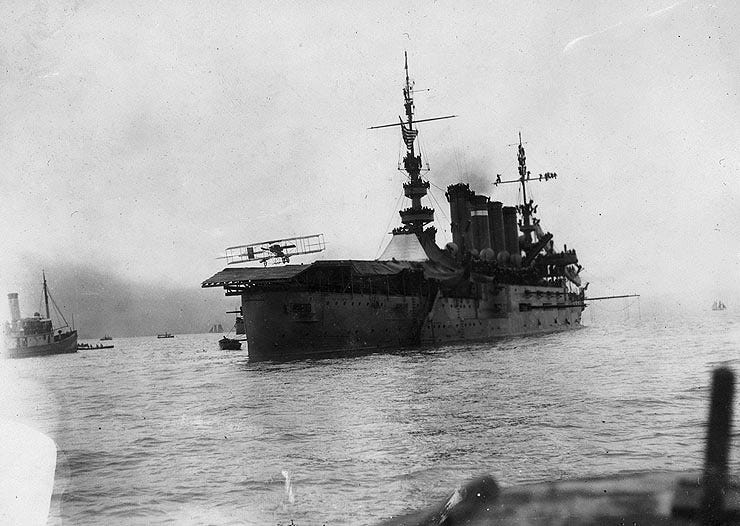

On 14 November 1910, Ely made history by becoming the first person to successfully take off from a ship. The ship in question was the light cruiser USS Birmingham, stationed in Hampton Roads, Virginia. Ely took off from a temporary wooden platform that had been erected on the deck of the cruiser, using a Curtiss pusher biplane for the flight. Despite facing poor weather conditions and barely avoiding disaster after his aircraft’s wheels dipped into the water after takeoff, Ely successfully completed the flight, landing onshore. This event marked a major milestone in aviation history, proving that aeroplanes could operate from ships at sea. Ely’s achievement would become one of the foundational moments in the development of the aircraft carrier, a military innovation that would revolutionise naval warfare.

Ely was not finished making aviation history. On 18 January 1911, he performed an even more daring feat: he successfully landed his aircraft on a ship. This time, the ship was the armoured cruiser USS Pennsylvania, anchored in San Francisco Bay. The landing was made possible by the construction of another temporary wooden platform on the ship’s deck. A makeshift arresting gear system, consisting of sandbags and ropes, was also installed to help stop the aircraft upon landing. Ely's aircraft, once again a Curtiss pusher, was fitted with a tailhook to catch the arresting gear. The landing was a success, making Ely the first person to land an aircraft on a ship, a feat that solidified his place in the annals of aviation history.

The success of this shipboard landing further demonstrated the potential for aircraft to operate in conjunction with naval forces, particularly in reconnaissance and combat support roles. Although the U.S. Navy did not immediately pursue the development of aircraft carriers, Ely’s achievements laid the groundwork for future innovations. The principles of shipboard takeoffs and landings that Ely demonstrated would eventually lead to the construction of purpose-built aircraft carriers in the 1920s and beyond, fundamentally changing naval warfare.

Despite his groundbreaking accomplishments, Ely never formally joined the military. His work with the Curtiss Aeroplane Company continued, and he remained an active pilot, performing in various airshows and exhibitions. Ely’s life, however, was tragically cut short. On 19 October 1911, just a few months after his historic landing on the USS Pennsylvania, Ely was participating in an airshow in Macon, Georgia. During the show, Ely attempted a manoeuvre but lost control of his aircraft. His plane crashed, and he was thrown from the cockpit, suffering fatal injuries. Ely was just 24 years old at the time of his death.

Though his career was brief, Eugene Ely’s impact on aviation was profound. His successful shipboard takeoff and landing were critical developments in the integration of aviation and naval forces, and his courage and innovation helped shape the future of military aviation. Ely’s work directly contributed to the eventual creation of aircraft carriers, which would go on to become a central component of naval strategy during the 20th century, particularly during World War II.

In recognition of his pioneering achievements, Ely was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by the United States. This honour, reserved for aviators who demonstrate heroism or extraordinary achievement during flight operations, was a testament to the lasting significance of Ely’s work. His legacy is remembered within both the aviation and naval communities, and his contributions are still celebrated as foundational moments in the history of flight.

Ely’s life and career serve as a reminder of the early days of aviation, a time when flight was still experimental and fraught with risk. Despite the dangers, Ely and his contemporaries pushed the boundaries of what was possible, demonstrating the vast potential of aircraft for both civilian and military purposes. His pioneering spirit and willingness to take risks helped to pave the way for future generations of pilots, engineers, and military strategists.

Today, Eugene Ely’s name is commemorated in various aviation history exhibits and museums, particularly those focused on naval aviation. His achievements in shipboard flight remain iconic, and he is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the early history of aviation. Although his life was tragically short, Ely’s contributions to the field of aviation had a lasting impact that continues to be felt more than a century after his historic flights.

(With apologies to Rhod Gilbert for stealing and then butchering his joke about eggs. Again, I stand someway beneath the shoulders of giants, thinking about what to pair with cheese)

I grew up dreaming of becoming a military pilot. Didn’t work out for a bunch of reasons. I didn’t have the grades for the Air Force Academy (I’m too tall for most USAF fighter jets anyway), there was NO WAY you’d catch me trying to take off or land on a ship at sea, and I didn’t know that A-10’s were Army planes..