Julius Caesar, I am sorry to report, did not invent a salad.

Neither did he add two months to the calendar; his reorganisation of the months took away the intercalary month that was sometimes added after February and jiggled the months about until they looked like they are today. This 'floating' month could be inserted at will into the schedule by the officials in charge of such things in order to lengthen the year-long term of office of political allies or shorten that of rivals. July was added after Caesar's death, and before that, it was known as Quintilis. August was Sextilis, hence September is the 'seventh' month and October the eighth, etc, etc. The only difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendar is the way Leap Years are calculated.

And, alas, I'm sorry to report that Julius Caesar was not born by Caesarean section. Caesareans in the ancient world were relatively common but were always performed after the mother had died, if both the mother and the fetus had died, or if the failure to remove the fetus would result in the death of both. No woman was recorded as surviving such a procedure until the year 1500. Julius Caesar's mother, Aurelia, not only survived his birth, but she led a comfortable existence into her sixties.

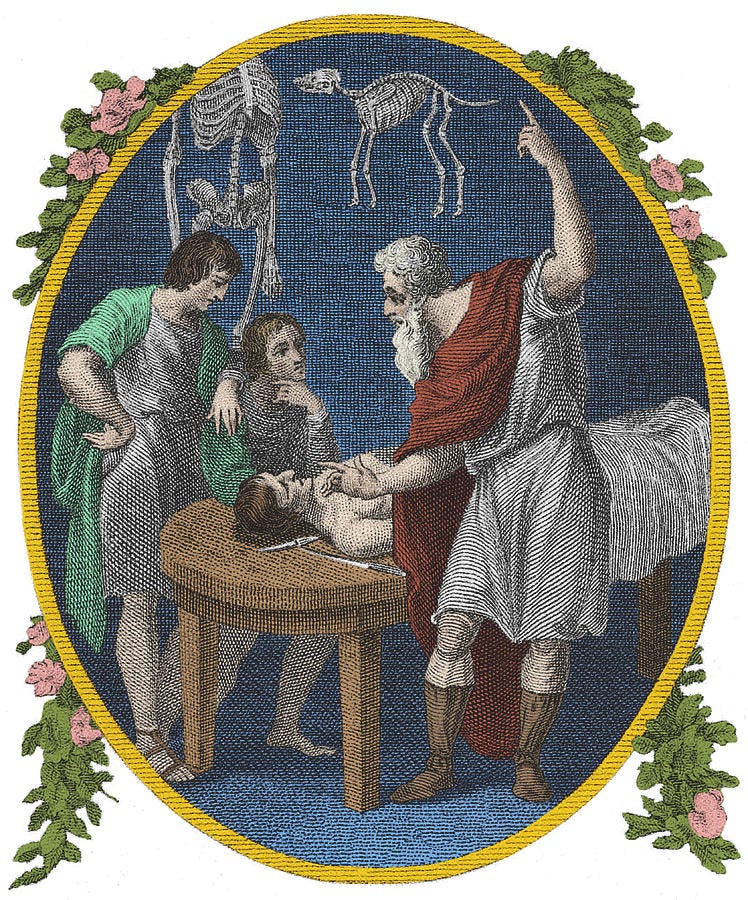

Women didn't survive such procedures not only because the operation itself was risky and childbirth in those days was staggeringly dangerous but because the surgeons who carried it out did so with what can only be described as rudimentary medical knowledge. That's not to say that, of course, they didn't operate at what was, back then, the cutting edge of medical science, but that the cutting edge of medical science was as blunt as some of the instruments they used to hack people about with.

So what were the chances of going under the surgeon's knife in ancient Rome and making it out alive again?

Firstly, we should define what we mean by 'surgery'. Surgery is, broadly, the branch of medical practice that treats injuries, diseases, and other conditions by the physical removal, repair, or readjustment of organs, bones, and tissues, often involving cutting into the body. So, for this article, we're not concerned with other branches of medicine that treat viruses or infections unless they result in a surgical procedure.

Roman surgeons, or medici, employed a variety of tools that have been well-documented through archaeological findings. The scalpellus, a small, sharp knife, was the primary instrument for making incisions. Other tools included bone drills, forceps, hooks, and probes, many of which have been unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum (Jackson, 1988). These instruments were typically made from bronze or iron and were designed for specific surgical tasks, such as extracting arrows or amputating limbs.

The training of Roman surgeons was largely informal, often involving apprenticeships under experienced practitioners. The Roman military played a significant role in advancing surgical knowledge, as battlefield injuries provided ample opportunities for practice and innovation. Surgeons were highly valued in Roman society, particularly within the army, where their skills were crucial for maintaining the health and efficiency of soldiers (Nutton, 2013).

One of the most common procedures was trepanation, the practice of drilling or scraping a hole into the skull, which was performed to treat head injuries and relieve intracranial pressure. Archaeological evidence, such as skulls with trepanation holes found in Britain and Gaul, suggests that this procedure was relatively common. Primary sources like Celsus' De Medicina provide detailed descriptions of the technique, indicating a sophisticated understanding of cranial anatomy. Celsus writes:

" The modiolus is a hollow cylindrical iron instrument with its lower edges serrated; in the middle of which is fixed a pin which is itself surrounded by an inner disc. The trepans are of two kinds; one like that used by smiths, the other longer in the blade, which begins in a sharp point, suddenly becomes larger, and again towards the other end becomes even smaller than just above the point. When the disease is so limited that the modiolus can include it, this is more serviceable; and if the bone is carious, the central pin is inserted into the hole; if there is black bone, a small pit is made with the angle of a chisel for the reception of the pin, so that, the pin being fixed, the modiolus when rotated cannot slip; it is then rotated like a trepan by means of a strap. The pressure must be such that it both bores and rotates; for if pressed lightly it makes little advance, if heavily it does not rotate. It is a good plan to drop in a little rose oil or milk, so that it may rotate more smoothly; but if too much is used the keenness of the instrument is blunted."

(Cels. Med. 8.3)

Amputations were another common surgical procedure, particularly in military contexts. Roman surgeons developed techniques to minimise blood loss and infection, such as the use of tourniquets and cauterisation. The survival rate for amputees was likely low due to the risk of infection and shock, but some patients did survive, as evidenced by healed amputation stumps found in archaeological sites (Baker, 2004). Celsus provides a detailed account of amputation:

"...if medicaments have failed to cure it, the limb, as I have stated elsewhere, must be amputated. But even that involves very great risk; for patients often die under the operation, either from loss of blood or syncope. It does not matter, however, whether the remedy is safe enough, since it is the only one. Therefore, between the sound and the diseased part, the flesh is to be cut through with a scalpel down to the bone, but this must not be done actually over a joint, and it is better that some of the sound part should be cut away than that any of the diseased part should be left behind. When the bone is reached, the sound flesh is drawn back from the bone and undercut from around it, so that in that part also some bone is bared; the bone is next to be cut through with a small saw as near as possible to the sound flesh which still adheres to it; next the face of the bone, which the saw has roughened, is smoothed down, and the skin drawn over it; this must be sufficiently loosened in an operation of this sort to cover the bone all over as completely as possible."

(Cels. Med. 7.33)

Battlefield surgeries were a critical aspect of Roman military medicine. Surgeons had to operate quickly and efficiently to save lives. The use of field hospitals, or valetudinaria, allowed for more organised and effective treatment of wounded soldiers. Primary sources like Vegetius' Epitoma Rei Militaris describe the rapid extraction of arrows and the treatment of wounds with vinegar and honey to prevent infection. Vegetius describes how arrows should be removed as quickly as possible to avoid infection. They could be drawn out with the use of forceps or, if the barbs didn't allow, an incision might be made on the opposite side of the wound, and the arrow teased along its path towards the newly made exit wound. The whole thing would then be treated against infection with sponges soaked in vinegar and honey.

Roman surgeons had a rudimentary understanding of the importance of cleanliness. Handily, Celsus gives us some advice about the sort of person who would make a fine surgeon:

"Now a surgeon should be youthful or at any rate nearer youth than age; with a strong and steady hand which never trembles, and ready to use the left hand as well as the right; with vision sharp and clear, and spirit undaunted; filled with pity, so that he wishes to cure his patient, yet is not moved by his cries, to go too fast, or cut less than is necessary; but he does everything just as if the cries of pain cause him no emotion."

(Cels. Med. 7)

What this describes is someone who can deafen himself to the agony of his patient as he operates and not waver as the poor soul wails in pain. It also, of course, goes to show how the patient was operated on without any serious form of pain control or anaesthesia.

Instruments were often cleaned with boiling water or vinegar, which provided some level of disinfection. The use of clean linen for bandages and the application of antiseptic substances like honey and wine also helped reduce the risk of infection (Scarborough, 1969). Celsus emphasises the importance of cleanliness in surgical practice:

"The part where the skin has not been brought over is to be covered with lint; and over that a sponge soaked in vinegar is to be bandaged on."

(Cels. Med. 7.33)

The prognosis for patients subjected to Roman surgery varied widely depending on the type of procedure and the skill of the surgeon. For relatively minor procedures like trepanation, survival rates could be as high as 50-60%, based on archaeological evidence of healed skulls (Baker, 2004). However, for more complex procedures like amputations and cesarean sections, survival rates were much lower, likely in the range of 10-20%. There is always the issue that surgeons would only operate on people they thought had any chance of survival. If the prognosis for the patient was deemed to be too much of a risk, the surgeon would just pass them over for a patient more likely to survive. Not least in their thoughts was the prospect of finding themselves in some sort of legal trouble for having a patient die under their care, so hacking about at someone who was likely to die anyway was as much about protecting the surgeon as it was about treating the patient.

The pioneering surgeon Galen cut his teeth working in the arena of his hometown, treating wounds both minor and catastrophic. he once claimed to have saved the life of a gladiator who had been completely disembowelled. He found that the standard treatment for open wounds on gladiators - bathe them in hot water, followed by a plaster made of boiled flour - was either useless or lethal. Instead, he soaked linen cloths in wine and placed them on the wounds. He then stitched the wounds and changed the dressings regularly for the next few days. Whether or not it worked, he obviously understood the antiseptic properties of alcohol.

For those who survived surgery, post-surgical life expectancy depended on the success of the procedure and the prevention of infection. Patients who underwent successful trepanation or minor wound treatments could expect to live relatively normal lives. However, those who survived major procedures like amputations often faced significant disabilities and a reduced quality of life (Jackson, 1988).

A problem in working out how many people died as a result of their surgery is that the sources are not always aware of why the patient died. Patients who might otherwise have survived had the surgeons had better knowledge of post-surgical care are recorded as dying of their primary wounds or of 'being weak' rather than anything to do with the surgery itself. The idea that the surgery killed the patient, not the initial problem, doesn't seem to have occurred to them. This, naturally, raises the question of whether the patient would have survived had the surgeon left them alone.

The prognosis for patients subjected to Roman surgery varied widely depending on the type of procedure and the skill of the surgeon. For relatively minor procedures like trepanation, survival rates could be as high as 50-60%, based on archaeological evidence of healed skulls (Baker, 2004). However, for more complex procedures like amputations and cesarean sections, survival rates were much lower, likely in the range of 10-20%.

When the survival rate was apparently so low, it does beg the question of whether the patient was better off taking his chances without the surgeon poking about inside them. You might have to just live with the toothache instead.

References and Further Reading

Baker, P. A. (2004). Roman Medical Instruments: Archaeological Interpretations of Their Possible Uses. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Celsus, A. C. De Medicina. Translated by W. G. Spencer (1935). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jackson, R. (1988). Doctors and Diseases in the Roman Empire. London: British Museum Press.

Nutton, V. (2013). Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Translated by H. Rackham (1942). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scarborough, J. (1969). Roman Medicine. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Vegetius, F. R. Epitoma Rei Militaris. Translated by N. P. Milner (1996). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Galen. (1916). On the Natural Faculties (A. J. Brock, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thanks for reading! Please feel free to share this article as much as you like.

If you’d like to support my work, you can do so by subscribing for free, or by taking out a monthly subscription, currently only $5 a month. Every penny goes towards helping me get more interesting and fun articles out there! There is also an annual plan.

Please do take the time to check out my collection of books, which you can find on Amazon or by clicking the link below. They make fantastic gifts or great reading on the train, in the bath, or smashing unruly Gauls during the conquering of the known world, should that be your thing.