The 3rd of November 182 AD, in the small town of Senepta, somewhere in the Oxyrhynchite division of Roman Egypt, was supposed to be a happy day. It was a festival day, and the streets were festooned with garlands and flowers. Sweetmeats hung from strings across the streets for people to scrabble for. Great bouquets of flowers hung from the dusty flat roofs of the tightly packed streets, and music filled the air. The climax of the whole show was the castanet players - a troop of spinning ballet dancers, clattering noisily through the crowds, chased by gangs of children, scratching through the dirt for the fallen treats and thrown coins.

Epaphroditos was eight years old, but small even for his age. He had the perpetually hungry frame of a slave child, and in the twisting limbs of the milling throng, he was lost, unable to see the exotic, dizzying dancers as they passed. So he found a staircase and scurried up onto the flat roof of his master’s house to get a better view. He was excited, very excited. Nothing exciting ever came out this far into the countryside, and he was not going to miss this for the world. Eager to get a better view, he leaned over the edge of the parapet, perhaps raised an arm to wave at the troupe as they spun past, lost his grip, slipped, and fell.

“… At a late hour of yesterday the sixth [of the Egyptian month Hathyr] while there was a festival in Senepta and cymbal-players were giving the performance as custom has it in front of the house of my son-in-law, Ploution the son of Aristodemos, his slave Epaphroditos aged about 8 years, wishing to lean over from the flat-roof of the said house to see the cymbal-players, fell and was killed. Presenting therefore this request I ask, if it please you, that you dispatch one of your assistants to Senepta so that the body of Epaphroditos may receive the suitable layout out and burial. …”

(P.Oxy. III 475)

The death of Epaphroditos was a tragedy, but one of many among the slave population of the Roman Empire. The question that we’re interested in, for our purposes, is what is going on with this papyrus. It was written by Hierax, a senior official (strategos) of the Oxyrhynchite nome, to an assistant, Claudius Serenos. In it, Hierax instructs Serenos to go to the village Senepta, together with a public physician, to examine the dead body, following a request by Leonides, alias Serenos, the father-in-law of Epaphroditos’ master, Ploution, son of Aristodemos. The outcome is not recorded, nor is what subsequently transpired, but added to Hierax’s note is a transcript of Leonides’ original petition.

Why are they going to all this trouble for what would appear to be nothing more than a tragic accident involving a slave boy? Slaves were technically possessions of their masters, and their death, which would not necessarily have been treated with a lack of compassion or empathy by the master, could simply have been dealt with by having the child’s body dealt with in the usual way.

But with possession comes other responsibilities, not least of which are taxes to be paid on the slave and perhaps by having an official confirm the death, the master is making sure he is no longer responsible for paying the taxes. However, if this were the case, why isn’t Ploution making the petition himself? Why is his father-in-law the one doing the writing?

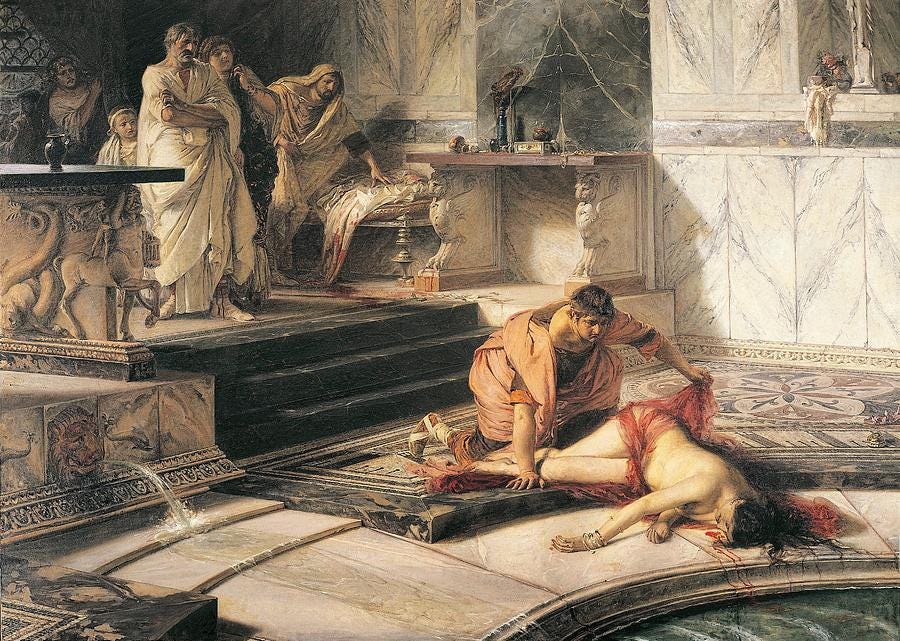

Although slaves were possessions, by the time of Commodus, rules had been in place for some time that restricted how badly a master could treat a slave. Random punishment, beatings, and maltreatment were illegal, as was the summary murder of a slave, which, at one point earlier in Roman history, had been perfectly legal. Perhaps then there is some suspicion about the death of the child, and Leonides suspects that his son-in-law was involved? Or, perhaps, someone else suspected that Ploution was involved, and Leonides had called in a doctor to inspect the body and determine the cause of death? If the doctor can confirm that the boy died after falling from the roof, it might look like nothing but a terrible and tragic accident, but if he were to find some other cause of death …

What we are seeing, perhaps, is the beginning of a forensic investigation into the death of a child. But just how common was this, and how else were crimes investigated in the Roman world?

How Did the Romans Solve Crimes?

Introduction: Investigating Crime in Ancient Rome

The investigation of crime in the Roman world presents something of a paradox. On the one hand, Rome developed one of the most sophisticated legal systems of antiquity, whose influence extended well into modern civil law traditions. On the other hand, there was no equivalent to an investigative police force, no standing detectives, and no established public prosecutor charged with discovering the truth behind crimes. Instead, responsibility for uncovering facts and establishing guilt rested in a combination of magistrates, advocates, witnesses, and the wider public, with heavy reliance on private initiative. When a death occurred under suspicious circumstances, or when theft, assault, or fraud was suspected, the first steps of enquiry were taken not by institutions but by families, neighbours, and, ultimately, magistrates and courts.

The Discovery of Crime and the First Steps of Investigation

Suspicious Deaths and Their Initial Interpretation

The most immediate investigative challenge faced by Romans was the sudden death of individuals under circumstances that raised suspicion. Unlike modern societies, Rome lacked coroners' inquests or medical examiners, meaning that the task of distinguishing between natural and criminal causes fell to families and magistrates. Cicero provides valuable testimony in Pro Cluentio, a speech concerned with poisoning. Here, the symptoms of illness, the manner of death, and the behaviour of those present became central to constructing suspicion (Cicero, Pro Cluentio 31). Cicero's strategy as advocate relied on persuading the court that certain physical signs pointed unmistakably to criminal poisoning. This illustrates how the earliest stage of Roman crime investigation depended upon rhetorical framing of evidence rather than technical medical analysis.

Tacitus' Annals demonstrates similar processes in elite cases. The celebrated example of Germanicus' death in AD 19 was interpreted by contemporaries as poisoning, based on circumstantial evidence such as Piso's enmity, suspicious objects hidden in Germanicus' house, and the victim's own accusations before death (Tacitus, Annals 2.69). No official autopsy existed; the investigative process was interpretive, shaped by testimony and motive analysis. In such cases, it was not only the body but the surrounding social context, hostility, rivalry, and opportunity that formed the investigative ground.

The Absence of Detectives and the Role of Magistrates

Rome lacked professional detectives. Instead, responsibility for uncovering crimes fell on magistrates, especially consuls and praetors in major cases, and aediles or local officials in more routine matters. During the Republic, extraordinary commissions of inquiry (quaestiones extraordinariae) could be created to investigate serious offences such as murder or treason, later replaced by standing courts (quaestiones perpetuae). Yet these bodies did not employ investigators in the modern sense. Their role was both to gather evidence and to adjudicate it, blurring the line between investigation and trial.

The vigiles, introduced under Augustus, served primarily as a fire brigade but also patrolled the streets at night and apprehended thieves (Frontinus, De aquis 2.105; Dig. 1.15.1). While they played a part in arresting offenders, their role was custodial, not investigative. Once an offender was seized, it was the magistrates and the accusing party who bore the burden of building a case.

Social Surveillance and Community Testimony

Roman society was intensely public, with households, neighbours, and clients constantly observing one another. Juvenal quips that "walls have ears" (Satires 9.105), capturing the sense that little escaped communal notice. This social surveillance played a central role in the discovery of crime. If a violent death occurred, neighbours and clients were among the first to raise an alarm, creating pressure for formal action.

Slaves were both potential witnesses and suspects. Roman law admitted their testimony only under torture when it concerned their masters (Dig. 48.18.1), revealing deep suspicion of their reliability and loyalty. In Roman society, a man's word was a critical display of his integrity and the higher up society that man stood, the more weight his word held. By the time one got to the Emperor, the veracity of his word could be so strong that it could distort reality. If an emperor said it was Sunday on a Monday, it was a Sunday. Conversely, those at the bottom couldn't be trusted to tell the truth, even if they were telling the truth and everyone knew they were. The same distortion happened at both ends of society, but in different directions. So if a slave told the same story before torture as after it, only the post-torture testimony could be believed, as it had been 'tested' by the scourge. Nonetheless, they were critical sources of information, often being present at the moment crimes occurred.

Epigraphy shows that crimes could be preserved in public memory. A funerary inscription from Aquileia memorialises a man killed unjustly, demanding remembrance of the offence (CIL V 1023). Such inscriptions served as enduring accusations, transforming crime into a matter of collective witness. The initial investigative process, therefore, was rooted in the combination of family initiative, community observation, and magistrates' willingness to respond.

Evidence, Testimony, and the Use of Torture

Witness Testimony as the Cornerstone of Roman Evidence

The principal form of evidence in Roman investigations was testimony. Cicero's speeches repeatedly emphasise the importance of witnesses, whether to character, to events, or to circumstantial details. In Pro Roscio Amerino, defending a man accused of parricide, Cicero highlights the absence of credible eyewitnesses and undermines the plausibility of hostile testimony (Cicero, Pro Roscio Amerino 20–22). In practice, "solving" a crime was often a matter of securing persuasive testimony rather than physical evidence.

The Digest preserves juristic discussion of the weight of witnesses. Ulpian insists that the credibility of testimony depended not simply on number but on consistency and character (Dig. 22.5.3). This underscores that investigative procedure was shaped less by forensic science than by moral evaluation of witnesses, rooted in Rome's honour culture.

Physical Evidence and the Examination of Wounds

Despite the absence of forensic medicine, Romans did engage with physical traces of crime. Seneca, describing the tyrant's fear of assassination, notes the scrutiny of wounds as indicators of intention (De Ira 1.18). Tacitus records how the body of Otho, who committed suicide in AD 69, was examined by soldiers who interpreted the location of the wound as evidence of noble self-slaughter (Histories 2.49). In criminal cases, wounds could reveal whether violence was accidental, suicidal, or homicidal.

Weapons also played a role. In Pro Milone, Cicero defends Milo against the charge of murdering Clodius, arguing that the position of weapons and the sequence of events exculpated his client (Cicero, Pro Milone 46). Here, forensic-style reasoning is applied: weapon-matching, reconstruction of the scene, and motive analysis all feature prominently. While lacking technical precision, these arguments reveal a Roman awareness of physical evidence as probative.

The Role of Confession and Coerced Testimony

Confession, whether voluntary or forced, carried great weight in Roman investigations. The Digest acknowledges the evidentiary value of confession, though jurists debated its reliability (Dig. 48.18.1). In practice, confessions were often extracted under duress, particularly from slaves. Torture (quaestio per tormenta) was regarded as a legitimate investigative tool. Cicero himself acknowledges this, though he criticises overreliance on tortured testimony as unreliable (In Verrem 2.5.63).

The legal distinction between slaves and citizens was crucial. Whilst slaves could be tortured for testimony, citizens were theoretically protected from such treatment. Yet emergencies or accusations of treason sometimes eroded this boundary, as Tacitus records under Tiberius, when citizens accused of conspiracy faced brutal interrogation (Annals 6.19). Torture was seen not only as punitive but as a tool to extract truth, however flawed its results.

Archaeological and Epigraphic Traces of Evidence-Gathering

Archaeology provides glimpses of investigative practice. Curse tablets (defixiones), often deposited at crime scenes or in temples, include pleas for divine revelation of thieves or murderers. One tablet from Londinium invokes the gods to reveal the thief of stolen goods, listing possible suspects (RIB 306). These inscriptions functioned as both magical appeals and quasi-investigative records, identifying suspects by name and preserving the crime in material form.

Epigraphic records also attest to penalties for false testimony, underscoring the centrality of truthful witness in investigative procedure (CIL VI 1527). These texts reveal a world where physical traces, written accusations, and divine appeals intersected in the search for truth.

Magistrates, Advocates, and the Public Construction of Truth

The Magistrate as Investigator and Judge

Magistrates such as praetors and consuls served as both investigators and adjudicators. In homicide cases, the quaestiones perpetuae, standing courts established in the late Republic, were convened to hear accusations. Yet these bodies lacked a distinct prosecutorial arm. The magistrate might oversee the collection of evidence, summon witnesses, and conduct preliminary hearings, but the initiative rested with private accusers. As Cicero notes, prosecutions for crimes such as extortion depended upon individuals stepping forward to act as accusatores (In Verrem 1.15).

This structure meant that the investigative process was inseparable from advocacy. Unlike modern systems with public prosecutors, the Roman model placed the burden of investigation and evidence-gathering squarely on those who brought accusations.

Advocates as De Facto Investigators

Cicero himself exemplifies the advocate as investigator. In defending Roscius, accused of murdering his father, Cicero painstakingly reconstructs events, examines motives, and introduces alternative suspects (Pro Roscio Amerino 30–34). His speech is not merely advocacy but an investigative narrative, piecing together testimonies, physical circumstances, and political context. Advocates often had to perform the work of detectives, assembling facts, examining witnesses, and framing evidence.

Quintilian, in his Institutio Oratoria, underscores that advocates must test the credibility of witnesses, investigate circumstances, and consider the plausibility of motives (Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria 5.7).

The Public Nature of Crime and Social Control

Rome's dense urban society meant that crime-solving relied on public scrutiny. Tacitus describes trials as theatre, where accusations and evidence were aired before large audiences (Annals 1.74). The construction of truth was therefore social as much as juridical.

Public inscriptions and graffiti further contributed to this culture. Graffiti from Pompeii accuses individuals of theft and violence, recording communal judgements outside formal courts (CIL IV 1877). In this sense, Roman society itself acted as an investigative body, gossip and accusation functioning as proto-policing.

The Limits of Roman Investigative Practice

Despite these mechanisms, the Roman system faced severe limitations. Torture produced unreliable testimony, private prosecutions skewed investigations towards the wealthy and powerful, and the absence of professional investigators left cases vulnerable to manipulation. Tacitus' account of Piso's trial for Germanicus' alleged murder demonstrates how suspicion, political rivalry, and rumour could outweigh firm evidence (Annals 3.15). The construction of guilt often reflected political necessity rather than objective truth.

Crime, Truth, and Justice in Roman Investigation

The Romans solved crimes through a patchwork of methods: immediate social suspicion, witness testimony, examination of physical traces, and a generous sprinkling of torture. Magistrates and advocates functioned both as investigators and arbiters, while communities preserved memory of crimes through inscriptions, graffiti, and oral testimony. Although they lacked professional police or forensic science, Romans nonetheless developed strategies of logical reasoning about wounds, motives, and circumstances that reflect a sort of proto-forensic thought.

Yet the system was limited by its reliance on private prosecution, the (somewhat ironic) unreliability of tortured confessions, and the pervasive influence of political and social terror. Ultimately, Roman crime-solving was less about neutral discovery of fact than about constructing persuasive narratives of guilt or innocence within a public, adversarial framework.

References and Further Reading.

Cicero. (1936). Pro Cluentio. In A. C. Clark (Ed.), M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes (Vol. 3). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cicero. (1917). Pro Roscio Amerino. In A. C. Clark (Ed.), M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cicero. (1935). Pro Milone. In A. C. Clark (Ed.), M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes (Vol. 4). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cicero. (1903). In Verrem. In A. C. Clark (Ed.), M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes (Vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Digest of Justinian. (1985). (A. Watson, Trans.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Frontinus. (1925). De aquis urbis Romae. In C. E. Bennett (Ed. & Trans.), Frontinus: The Stratagems and the Aqueducts of Rome. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Juvenal. (1961). Satires. (S. M. Braund, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Quintilian. (1920). Institutio Oratoria. (H. E. Butler, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

RIB (Roman Inscriptions of Britain). (1965–). Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seneca. (1928). De Ira. (J. W. Basore, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Suetonius. (2025). The Twelve Caesars (J. Coverley, Trans.). The Cych Press.

Tacitus. (1931). Annals. (J. Jackson, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tacitus. (1925). Histories. (C. H. Moore, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

CIL (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum). (1863–). Berlin: De Gruyter.

The Twelve Caesars, quoted above and translated by yours truly, is available as an ebook by clicking the link below or online everywhere you expect to find books.

It seems to me you just created a concept for a detective drama series (even if the Romans didn't have detectives). What would it be called I wonder...? "Mystery of the Bloody Toga..." "A Scandal in Oxyrhynchite...."

This article reminded me of Bulgakov’s Master and the Margherita!