Whilst it is very easy to poke fun at how historically inaccurate movies such as Gladiator are, which, as regular readers know, is something of a common target of mine, they do get some things right and in this respect, it is undoubtedly true that the emperor Commodus was a complete arsehole. That's not saying much, of course, because you could make a good argument that all of the Roman emperors were, in one way or another, complete arseholes, even the ones we consider 'good' - certainly by the lovely, civilised, genocidal, warmongering standards that we hold ourselves by. He also loved to 'fight' in the arena, so the movie got that right, too. Although the term 'fight' might be replaced by 'killed things and people that were tied up first.'

On one very famous occasion, he was busy working his way through a flock of ostriches with a bow and arrow when he took the severed head of one and approached the seats where the senators were relaxing, fanning themselves in the noon sun, waggling the bird's head comically and leering at them with the grin of a man who suggests that they were all soon for the same fate. Cassius Dio was so terrified of the implied threat that he had to chew on his own hat (well, the leaves from his laurel wreath) to stop from screaming out in hysterical terror. All this soon led to the emperor's murder, and in this respect, the reality was, perhaps, less cinematic but certainly more in keeping with the way such tyrants met their deaths.

When his mistress, Marcia, found a list of people he intended to have murdered, including herself, she decided to act, and alongside the prefect Laetus and his freedman Eclectus, she slipped poison into his sausage supper and waited for it to do the rest. It didn't work, although it did make him rather unwell, so he slipped off to take a bath in the hope he would feel better, followed closely by his wrestling partner, Narcissus, who finished him off with his bare hands.

Roman history is full of instances where people are poisoned and sometimes it takes effect almost immediately, and at other times, it does little more than cause an upset stomach. This, incongruously, made it a rather good cover for killing people, particularly if applied to foodstuffs that could be blamed for any subsequent illness, such as mushrooms. If it didn't work the first time, just blame the food. Nero had several goes at feeding poison to his adopted brother Britannicus, most of which just made him groggy until finally, he had a batch mixed that was so potent that it killed him instantly (and also poisoned the future emperor Titus, who ate from the same dish and was ill for a long time afterwards. (Suetonius, Life of Titus, 2)).

But what sort of poison could they have used that was either inconsistent or instantly deadly? Did they just use toxic mushrooms? Where did they get the poison from? Let us find out!

Roman Attitudes Toward Poison – Legal, Philosophical, and Social Perspectives

The concept of poison (venenum) in Roman society elicited both fear and fascination. From as early as the Republican period, Romans understood poison not merely as a means of clandestine homicide but also as a substance with ambivalent moral and medical potential. The word venenum itself had a semantic ambiguity; while in later Latin, it acquired an almost exclusively negative connotation, in earlier periods, it could denote any potion or drug, whether curative, recreational, or harmful (Adams, 1995). This duality underpinned much of Roman engagement with toxic substances: poison was both peril and remedy, deeply embedded in medical, legal, and political discourse.

The Lex Cornelia de Sicariis et Veneficiis

One of the earliest and most important legal measures taken against poisoning in Rome was the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis, promulgated under the dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 81 BC. Although fragmentary, sources such as Cicero and Ulpian suggest that this law targeted both assassins (sicarii) and poisoners (venefici) under a single legal framework, treating poisoning as a form of murder by covert means (Cicero, Pro Cluentio, 54; Ulpian, Digest 48.8.3). The statute appears to have criminalised not only the act of administering a deadly poison but also the mere possession or distribution of harmful substances and possibly even certain forms of medical malpractice if they led to death.

Notably, the Lex Cornelia marked a significant shift in Roman legal culture, emphasising the prosecution of intent as well as action. It defined veneficium broadly, allowing for trials in cases where poison was suspected but unproven by physical evidence. This legal latitude perhaps mirrors the cultural anxieties about poison's invisible, secretive nature—a crime that, unlike stabbing or strangulation, left no immediate trace (Bauman, 1996).

The law had a long-lasting influence. Tacitus (Annals 2.69) notes its invocation in several early Imperial trials, including those involving accusations of poisoning for political ends. The persistence of such prosecutions into the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD indicates that veneficium remained a serious and feared offence, warranting both legal attention and public spectacle.

Cultural Fears and the "Poison Panic" of 331 BC

Long before Sulla's formal codification of anti-poison legislation, the Romans were gripped by sporadic episodes of what modern scholars have termed "poison panics." One of the most well-documented of these occurred in 331 BC, as recorded by Livy (Ab Urbe Condita 8.18).

According to Livy, a sudden outbreak of unexplained deaths across Rome prompted mass hysteria. An investigation led to the trial and execution of a group of Roman matrons accused of poisoning their husbands and others in their communities. The initial number of condemned women was twenty, but Livy states that eventually, as many as 170 were implicated. The trial, conducted without due legal process, was largely based on confessions and public outrage.

Livy's account is ambiguous. While the narrative strongly implies actual poisonings, he also notes that some contemporaries believed the deaths were due to plague and the accusations fabricated. Regardless of the truth, the event marks a critical moment in Roman cultural memory, shaping the association of poison with feminine treachery, domestic betrayal, and epidemic fear. It also illustrates how poison, whether real or perceived, could fracture social trust and incite extrajudicial responses.

Philosophical Engagements with Poison

Roman intellectuals also engaged with poison as an abstract moral and philosophical problem. Seneca the Younger, for instance, in De Ira (2.33), discusses poison metaphorically, comparing wrath to a slow-working toxin that erodes the soul. Elsewhere, in his Epistles (95.28), he refers to moral corruption as a form of poisoning, again reinforcing the conceptual duality of poison as something more than mere physical harm. Cicero, in his philosophical treatises such as De Officiis, also touches on the idea of covert harm, drawing analogies between poisoners and those who undermine the state through secret treason or perjury (Cicero, De Officiis 1.13).

Such rhetorical uses of venenum not only illustrate the term's metaphorical richness but also reflect genuine Roman fears of hidden moral decay. The clandestine nature of poisoning made it a frequent trope in ethical discussions about trust, justice, and the moral fabric of society.

The Social Context: Women, Slaves, and the Invisible Threat

Roman society often associated the use of poison with social "outsiders": women, slaves, foreigners, and practitioners of magia. Accusations of poisoning frequently coincided with broader anxieties about social subversion and the erosion of patriarchal order. The historian Valerius Maximus, in Facta et Dicta Memorabilia (8.1.absol.), records several instances of women allegedly employing poison against family members, reinforcing the cultural stereotype of the venefica—a sorceress or poisoner-woman operating within the domestic sphere.

Similarly, Tacitus describes how poisonings were often linked to the employment of astrologers, herbalists, and other individuals who occupied liminal roles. In the case of the notorious Locusta, an alleged professional poisoner in the time of Nero, Tacitus (Annals 12.66, 13.15) implies that her expertise lay in preparing specific toxic agents on imperial order—an indication that such figures were simultaneously reviled and indispensable.

This social coding of poison as the tool of the marginalised or the morally corrupt elite reinforced its cultural power. Roman elites feared not only the poison itself but the erosion of the values it seemed to represent: treachery, foreignness, and the perversion of domestic loyalty.

Types of Poisons Used in the Roman World: Sources, Symptoms, and Administration Methods

Roman knowledge of poisons derived from a complex interplay of folk medicine, natural philosophy, empirical observation, and long-standing Mediterranean traditions of pharmacology. By the late Republic and into the Imperial period, Roman writers—drawing on earlier Greek sources—had compiled extensive materia medica cataloguing dozens of toxic substances, including their origins, properties, and antidotes. Roman understanding of poisons was neither rudimentary nor mythological; it was systematic, cumulative, and often clinically sophisticated.

Botanical Poisons

Aconitum (Aconite or Wolfsbane)

Perhaps the most feared plant in Roman toxicology, aconitum was widely known for its potency and near-certain lethality. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (25.26; 27.2), calls it the "queen of poisons" and recounts that it originated in the region of Pontus in Asia Minor. According to myth, it sprang from the spittle of Cerberus during Hercules' twelfth labour—a detail that, while mythical, underscores its reputation for infernal power. The plant's active alkaloid, aconitine, induces rapid onset of neurological symptoms: tingling, numbness, vomiting, motor paralysis, and death through asphyxiation. Dioscorides (De Materia Medica, 4.77) warns that even minute amounts are fatal, describing both oral and dermal toxicity.

Roman accounts indicate that aconite was often administered in wine, honeyed drinks, or food, given its extremely bitter taste and swift action. Celsus (5.25.3) confirms its use in both homicide and medicine, though he classifies it among drugs of "exceptional risk." Its antidotes were few and generally ineffective, often involving vomiting agents or poultices.

Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

Known chiefly from the death of Socrates, hemlock was widely cultivated and recognised in Roman pharmacology. Dioscorides (4.80) and Galen (De Antidotis, 2.3) describe its action as a progressive muscular paralysis leading to respiratory failure. Unlike aconite, hemlock acted more slowly and was sometimes employed in state executions. In rare cases, small quantities were used as analgesics or sedatives.

Pliny (HN 20.197) details multiple species of hemlock, noting that the most toxic grew in colder climates. He identifies typical symptoms as cold extremities, sluggish speech, and a gradual loss of motor control, distinguishing it from poisons that induced convulsions. The Romans were aware that boiling or drying the plant altered its potency, making preparation a key factor in its effectiveness.

Atropa Belladonna and Mandragora (Deadly Nightshade and Mandrake)

Both Atropa belladonna and mandragora were well-known to Roman pharmacologists, often associated with sedative or hallucinogenic properties. Pliny (HN 25.94) and Dioscorides (4.76) mention their use in surgical anaesthesia and pain relief but also warn of their toxicity. Mandrake, in particular, appears in several magical and quasi-medical contexts, such as love potions and sleeping draughts. Pliny recounts cases of madness and death when doses were misjudged. Galen includes belladonna in his pharmacopoeia but only in controlled mixtures, usually accompanied by strong purgatives or emetics.

Because these substances produced delirium, hallucinations, and unconsciousness, they were useful not only for homicide but also for manipulation or sexual assault—a fact alluded to obliquely in Roman poetry and invective literature.

Mineral and Metallic Poisons

Arsenic (Arsenikon)

Arsenic compounds, especially arsenic trioxide, were known in both Greek and Roman toxicology, although the terminology often overlaps with that for orpiment and realgar (arsenic sulfides). Dioscorides (5.120) describes its use as a rat poison and cautions against its presence in makeup and depilatory creams. Arsenic was tasteless when refined, making it suitable for covert use in food or drink.

Pliny (HN 34.167) and Vitruvius (De Architectura 8.6.11) comment on arsenic-laced pigments and their toxic effects on painters and artisans. Although direct accounts of arsenic poisoning are rare in narrative histories, its forensic potential is apparent in later Imperial legal cases, especially where symptoms involved systemic organ failure without external signs.

Lead (Plumbum)

Although not traditionally classified as a poison in literary accounts, lead was omnipresent in Roman life and increasingly recognised by modern scholars as a chronic toxin. Romans used lead in pipes and cookware and as a sweetening agent in defrutum, a grape syrup used in cooking and wine. While Pliny (HN 33.117) extols its usefulness, he does note its "pernicious vapours." Celsus (6.6.12) includes lead among causes of abdominal pain and pallor, symptoms consistent with modern understandings of lead poisoning.

Evidence from osteoarchaeology supports this. Studies of Roman skeletons show high levels of lead accumulation, especially in urban populations (Montgomery et al., 2010). Although rarely used deliberately for poisoning, its medical implications were profound and pervasive.

Animal-Based Poisons and Exotics

While less common, Romans also employed animal-derived poisons and exotic toxins imported from the East. Pliny (HN 29.33) discusses the poison glands of certain serpents, especially vipers and asps, noting their swift action and use in military or gladiatorial contexts. Scorpions, toads, and even insects were also cited in recipes for venomous salves or tinctures.

Most notorious were imported poisons from India and Parthia. Roman authors viewed these with a mixture of awe and scepticism. Lucan (Pharsalia 9.614–9.740) describes an elaborate toxic arsenal of Eastern origin, including slow-working, incurable poisons said to turn the blood black. While often hyperbolic, such descriptions reveal Roman fascination with the pharmacological sophistication of their eastern neighbours.

Methods of Administration

Poison was most often administered orally, masked in food or drink. Roman writers frequently refer to poisoned wine, honey, and sweet pastries—items associated with hospitality and trust. Martial (Epigrams 3.17), for instance, accuses a rival of "serving venom on a fig," and Tacitus (Annals 12.66) implies that Claudius was given poisoned mushrooms.

Other methods included topical application (especially for neurotoxins), vaginal suppositories, inhalation, or infected needles. Locusta's recipes, as described by Tacitus and Suetonius, likely included time-release compounds, suggesting an advanced knowledge of dosage, solubility, and onset time (Suetonius, Nero 33).

There is also epigraphic and archaeological evidence of poison containers and labelled phialae veneficae (poison bottles), although few have been chemically analysed due to contamination or decomposition. Medical writers like Scribonius Largus preserved detailed instructions on antidotes and toxic mixtures, implying a robust technical understanding of poison's preparation and counteraction.

Prominent Alleged Historical Cases of Poisoning in Rome

Accusations of poisoning punctuate the historical narrative of Rome from the late Republic through the Imperial period, often surfacing during succession crises, political rivalries, or dynastic disputes. Though proof in the modern forensic sense is rarely available, ancient historians such as Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio offer detailed accounts of suspected poisonings among the Roman elite. These cases were rarely investigated using physical evidence; rather, motive, circumstantial timing, and dramatic narrative structure were the primary indicators of guilt.

The Death of Claudius (AD 54)

Perhaps the most infamous Roman case of poisoning concerns the death of the emperor Claudius. According to Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, Claudius was allegedly poisoned by his fourth wife, Agrippina the Younger, to ensure the succession of her biological son, Nero.

Tacitus (Annals 12.64–67) provides the most detailed account. He reports that the poison was administered in a dish of mushrooms—referred to mockingly by later authors as "the food of the gods." The toxic agent was prepared by the notorious poisoner Locusta, and the dose was delivered either by the imperial physician Xenophon or a eunuch serving in the household. Tacitus notes conflicting versions: in one, Claudius immediately fell unconscious; in another, the poison only mildly affected him, requiring a second dose delivered via a poisoned feather inserted into his throat under the pretext of inducing vomiting.

Suetonius (Claudius 44) repeats similar allegations, though his tone is more satirical. He affirms that mushrooms were the delivery vehicle and adds that Nero later referred to mushrooms as "the food of the gods" in reference to their role in deifying Claudius through death.

Cassius Dio (Roman History 60.34–35) corroborates the basic account, citing Agrippina's ambition and the political necessity of removing Claudius before he could name Britannicus, his son by a previous wife, as his heir.

Despite the consensus among ancient writers, there is no forensic evidence of poisoning. However, the coordinated testimonies, combined with the political gain Nero obtained, have led most ancient and modern commentators to accept the account as historically plausible.

The Death of Britannicus (AD 55)

Britannicus, the teenage son of Claudius and direct rival to Nero, died suddenly at a banquet less than a year after his father's death. Tacitus (Annals 13.15–17) offers a vivid narrative of the event. According to his account, Nero invited Britannicus to dine and, during the meal, served him a cup of wine that had been deliberately cooled with poisoned water. When Britannicus collapsed and began to convulse, Nero claimed that he had merely reacted to a cold drink. Britannicus died shortly thereafter.

Tacitus explicitly names Locusta as the poisoner and records that Nero, dissatisfied with her first preparation (which had too slow an onset), forced her to refine the formula under duress. The resulting compound killed Britannicus almost instantly. Locusta was rewarded with a pardon and land, and subsequently trained others in the art of poisoning under imperial patronage.

Suetonius (Nero 33) confirms the use of poison and Locusta's involvement, adding that Nero frequently consulted her for future poisons. The calculated nature of Britannicus's murder—timed just before his formal investiture into adulthood—indicates the extent to which poison was used to eliminate threats to imperial succession.

The Death of Drusus the Elder (9 BC)

Drusus the Elder, son of Livia and brother of Tiberius, died suddenly during a military campaign in Germany. While his death was officially attributed to injuries from a fall off a horse, later rumours alleged poisoning.

Cassius Dio (Roman History 55.1) briefly notes the suspicion but dismisses it as hearsay. However, Suetonius (Tiberius 62) recounts a posthumous rumour that Drusus had been murdered on the orders of Augustus or at the behest of Livia to ensure Tiberius's position in the line of succession. No definitive proof was ever provided, and the lack of narrative coherence in the sources suggests that this poisoning, if it occurred, remains speculative even by ancient standards.

The Case of Gnaeus Piso and Germanicus (AD 19)

The rivalry between Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, governor of Syria, and Germanicus, the adopted son of Tiberius and heir apparent, culminated in Germanicus's mysterious death in Antioch. Tacitus devotes substantial attention to the affair in Annals 2.69–83.

Tacitus reports that Germanicus, after falling ill, accused Piso and his wife Plancina of poisoning him, bolstering the claim by pointing to suspicious objects—human remains, spells, and leaden tablets—found in his house. Piso was recalled to Rome and tried for treason and murder. Though the trial revealed no direct evidence of poison, Piso died (likely by suicide) before a verdict could be rendered. Tacitus speculates that Tiberius may have orchestrated events to protect himself from association with Piso or to eliminate Germanicus discreetly.

This case is remarkable not only for its political implications but for the blending of poisoning with magical rites and veneficium, reflecting the Roman belief that poison and sorcery were often intertwined.

The Case of Junia Silana and Agrippina (AD 55)

According to Tacitus (Annals 13.19–22), Junia Silana was accused of plotting to poison Agrippina the Younger using an intermediary named Calvisius. The plot was uncovered, and Silana was exiled. While no poisoning occurred, the case illustrates how accusations of veneficium functioned as political weapons. The senate and emperor treated even unfulfilled poison plots as grave offences.

The Poisoning of Lucius Silanus (AD 49)

Lucius Junius Silanus Torquatus, betrothed to Octavia (the daughter of Claudius), was accused of incest and forced to commit suicide shortly before Claudius's marriage to Agrippina. Tacitus (Annals 12.3) suggests that Agrippina orchestrated the scandal to clear the path for Nero. While no poison is alleged explicitly, the case reflects the frequent pairing of personal scandal, sudden death, and political gain characteristic of Roman poisoning narratives.

Poison as Political and Criminal Tool: Succession, Assassination, and State Violence

Poison occupied a unique space in the Roman repertoire of violence—one that straddled legality and criminality, secrecy and ceremony. While the sword, the arena, or the cross served as highly visible methods of punishment and coercion, poison was reserved for the private, the covert, and the deniable. Its clandestine nature made it ideally suited for elite political struggles, familial disputes, and succession crises. As Roman historians make clear, poison was not the weapon of the masses but of the powerful —a tool for those with access to kitchens, physicians, and the imperial inner circle.

Poisoning in the Context of Succession

One of the most persistent themes in imperial Roman history is the strategic use of poison to manipulate succession. In the Julio-Claudian dynasty especially, political power was transferred not simply through inheritance or appointment but through elimination. The alleged murders of Claudius and Britannicus exemplify this dynamic. As detailed in Tacitus (Annals 12.66; 13.15), Nero's path to the throne was smoothed through two carefully timed acts of poisoning—first of his stepfather Claudius, and then of his stepbrother, Britannicus, the legitimate heir. The implication in both cases is that poison offered a cleaner, less disruptive form of dynastic control than civil war or exile.

Similarly, the earlier suspicions surrounding the deaths of Drusus the Elder and Germanicus show that poisoning was feared not only as an act of treachery but as a political weapon deployed to tip the balance of imperial succession. As Roman historians repeatedly underscore, such deaths were often not investigated through forensic methods but were judged according to who stood to benefit, a logic embedded in Roman ideas of motive and culpability.

The historian Cassius Dio (Roman History 60.34–35) implies that within the imperial household, poison was more than murder—it was policy. When an emperor's survival or succession plan was threatened, the use of poison could be interpreted not as a deviation from order but as its preservation through pre-emptive action.

Criminal Veneficium and Urban Anxieties

Beyond palace intrigue, poison was also associated with criminality in urban settings, particularly in cases involving slaves, freedpersons, or women. The Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis explicitly classified veneficium (poisoning) as a criminal offence equivalent to murder, a designation that reflected both its lethality and its subversive character. The law was applied not only to elite political cases but also to accusations of domestic murder, inheritance fraud, and even professional malpractice.

Cicero's defence in Pro Cluentio (66–70) deals extensively with allegations of poisoning, exposing how the mere suspicion of veneficium could tarnish reputations and provoke legal action, even when evidence was circumstantial. In urban Rome, poison was imagined as a pervasive threat: undetectable, deniable, and often associated with domestic betrayal. The fear of being poisoned by a slave, concubine, or neighbour was reinforced by stories of mass poisonings, such as the alleged "poison panic" of 331 BC (Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 8.18), in which over a hundred Roman women were executed for purportedly murdering their husbands with illicit brews.

These narratives helped reinforce elite dominance by casting subaltern groups as latent threats to households and cities. Poisoning became a symbolic reversal of the social order: the tool by which the weak could destroy the strong, the private could upend the public.

Poison as an Instrument of Judicial Execution

While primarily associated with crime or conspiracy, poison was also—though rarely—used as an official means of execution. The most transparent case comes from Rome's philosophical inheritance of the Greek model. Socrates' execution by hemlock in 399 BC influenced later Roman practices, particularly in how poison was imagined as a 'civilised' form of death: quiet, internal, and less degrading than public torture.

There is limited evidence for state-sanctioned poison executions in the Roman context. However, some political suicides were likely encouraged or facilitated by poison, blurring the line between voluntary death and coerced elimination. Tacitus (Annals 16.30) and Suetonius (Nero 37) describe how senators and nobles under imperial suspicion were offered the "honour" of self-destruction, and it is plausible that some used poison to comply quickly and painlessly. For instance, the Stoic philosopher Seneca, forced to commit suicide under Nero's orders, attempted several methods, including bleeding and hemlock, before finally succumbing to suffocation (Tacitus, Annals 15.63–64).

More definitively, poisoned chalices or concoctions appear in literary depictions of punishment or mercy killings, especially when expediency or secrecy was required. In such cases, poison served as a controlled mechanism of death, one that allowed the state or its agents to dispose of undesirables without the spectacle of formal trial or execution.

Poison and Political Purges

Under emperors such as Nero, Domitian, and Commodus, the fear of political purges—executed via both open violence and covert poisoning—shaped senatorial and equestrian politics. The use of informants (delatores), combined with suspicion of veneficium, created a political atmosphere in which influential individuals might fall not by sword or rebellion but by a dose of untraceable toxin.

Nero's court, in particular, cultivated a system in which poisons became tools of bureaucratic efficiency. Tacitus (Annals 13.15) describes Nero employing Locusta to develop a stable of poisons tailored to different symptoms and delays, suggesting an almost institutionalisation of toxicology within the imperial household. Locusta's elevation to a sort of court position—complete with pupils, property, and impunity—reveals how poison could be bureaucratised for regime maintenance.

Similarly, under Domitian (AD 81–96), accusations of poisoning and treason flourished in tandem. Suetonius (Domitian 10) and Pliny the Younger (Epistulae 4.9) portray a paranoid court in which sudden deaths were often assumed to be politically motivated and in which poisonings were never far from suspicion.

Poison and Fear of Foreign Subversion

Finally, poison's use and symbolism in Roman political life were often racialised or linked to foreign enemies. As Pliny the Elder writes in Natural History (20.3; 29.8), the East—especially Parthia and India—was imagined as a land of sophisticated toxins and unscrupulous poisoners. Roman fears of Eastern subversion were both xenophobic and strategic: poison symbolised the kind of underhanded, un-Roman threat that could destabilise the principate.

Lucan's Pharsalia (9.614–40) mythologises exotic poisons brought back by Pompey's armies, hinting at how conquest could turn against the conqueror. Thus, poison became a metaphor not only for political intrigue but for imperial fragility and the consequences of cultural hybridity.

The Role of Professional Poisoners in Roman Society: Locusta and the Legal-Cultural Response

The spectre of the professional poisoner loomed large in Roman cultural imagination, fusing fears of science, secrecy, and subversion into a single, morally transgressive figure. While most poisonings in Roman texts are ascribed to individuals acting within familial or political networks, a distinct category of expert poisoners—venefici or veneficae—emerges in both legal texts and historical narratives. These were not merely individuals who used poison, but specialists capable of preparing, refining, and administering lethal substances with skill and discretion. The most infamous of these was Locusta, whose life and reputation provide a unique window into Roman attitudes toward professional poisoning and the state's ambivalent relationship with those who mastered its deadly arts.

Locusta: Imperial Assassin and State Asset

Locusta operated during the reigns of Claudius and Nero, gaining prominence through her involvement in two of the most politically significant poisonings in Roman imperial history: the alleged murders of Claudius and Britannicus. Tacitus (Annals 12.66; 13.15), Suetonius (Nero 33), and Cassius Dio (Roman History 61.34) all attest to her pivotal role in crafting and delivering these poisons.

According to Tacitus, Locusta was initially imprisoned for her role in illicit poisonings. Nero, upon deciding to remove Britannicus, released her and ordered her to prepare a fast-acting and untraceable poison. Her first attempt was too slow, and Nero, reportedly furious, demanded a more immediate and violent agent. Locusta complied, testing the improved compound on a condemned slave. Satisfied with the result, Nero used the poison on Britannicus, who died publicly and swiftly during a banquet (Tacitus, Annals 13.15).

Following her service to the emperor, Locusta was richly rewarded. Suetonius records that Nero gave her land and pupils to train, effectively institutionalising her as a state poisoner. She became a symbol not only of female criminality and scientific expertise but also of imperial hypocrisy: she was condemned, then pardoned and professionalised. Her status under Nero represents the clearest case in which toxicology became a recognised, if secretive, tool of state violence.

Legal Response: The Lex Cornelia and Public Execution

Despite Locusta's period of imperial favour, her eventual downfall under Galba underscores the precariousness of her position and the Roman state's formal condemnation of her profession. After Nero died in AD 68, Galba sought to erase the memory of his predecessor's abuses. Locusta was arrested, paraded as a symbol of tyranny and corruption, and executed—likely by public strangulation (Dio, Roman History 63.3). Her demise served as both a moral cleansing and a political theatre.

Locusta's story illustrates the double standard of Roman legal policy toward poisoners. Under the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis, veneficium was a capital crime. Yet that same law was selectively applied, especially when poisoners were useful to those in power. Ulpian, in the Digest (48.8.3), confirms that those convicted of veneficium were to be executed, typically by vivicomburium—burning alive—or thrown to wild beasts, depending on their social status. Women of lower status were particularly vulnerable to such punishments, reinforcing the gendered nature of Roman legal enforcement.

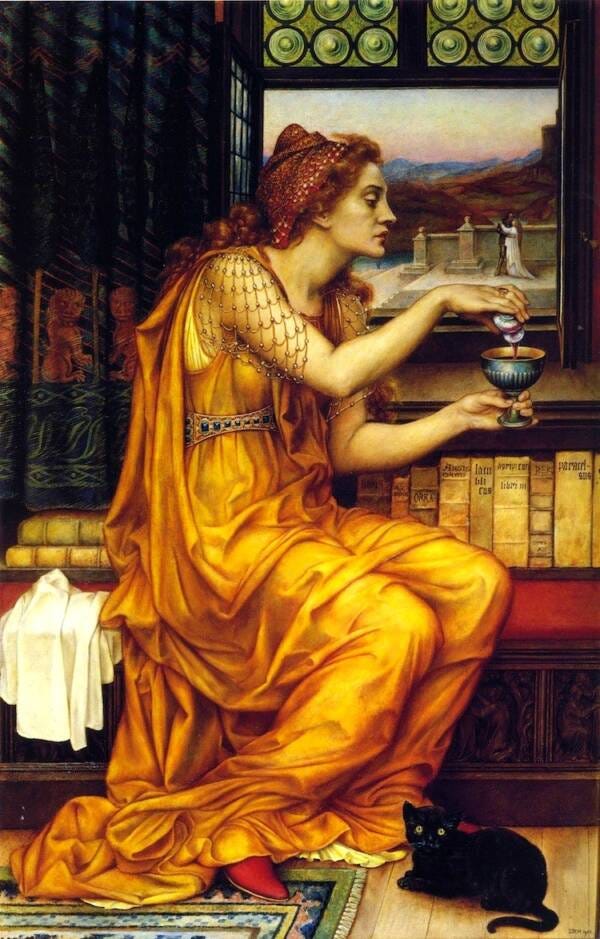

Gender and the Poisoning Stereotype

Locusta was not an anomaly in Roman cultural discourse but part of a broader archetype: the venefica, a woman who used secret knowledge and potions to subvert male authority. Literary and moralising texts often conflated poisoning with witchcraft and sexual deviance. Horace, in Epodes 5 and 17, describes venomous women as practitioners of black magic, makers of abortifacients, and disturbers of domestic harmony. Juvenal, in Satire 6.620–635, imagines noblewomen concocting poisons in private, suggesting that no husband could trust his wife entirely.

This literary stereotype had legal consequences. As noted in Valerius Maximus (Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 8.1), women accused of poisoning—even in cases of illness or unexplained death—were liable to be prosecuted with little evidence beyond rumour or confession. The mass executions of Roman matrons in 331 BC (Livy 8.18) serve as a chilling example of how suspicion alone could lead to lethal consequences for women associated with domestic pharmacology.

Professional Poisoners and Medical Knowledge

The line between professional poisoner and medical expert was often razor-thin. The very same techniques used to refine antidotes and therapeutic compounds were applicable to the manufacture of deadly toxins. Roman physicians, especially those operating in elite households, were suspected of both healing and harming. Scribonius Largus and Galen explicitly discuss the use of toxic agents in carefully measured doses for pain relief, sedation, and even euthanasia.

This overlap created a category of ambiguous professionals: herbalists, midwives, perfumers, and doctors—many of whom, particularly in provincial or rural settings, were women. While not all were poisoners, their access to toxic substances made them frequent targets of legal suspicion and cultural scorn. In this context, Locusta's "academy" under Nero may have drawn on existing traditions of pharmacological apprenticeship, albeit for illicit ends.

The Legacy of the Venefica

Locusta's notoriety outlived her execution. In later Roman and medieval texts, she became a byword for female depravity and cunning. The Christian apologists Lactantius and Jerome refer to her as emblematic of pagan corruption. By the 4th century AD, her name had become synonymous with sorcery, and she was often cited in moral discourses warning against astrology, herbalism, and the perils of unnatural female learning.

Yet her career also testifies to the permeability of moral boundaries in imperial Rome. The same technical expertise that brought death also brought state protection, institutional support, and social mobility—albeit briefly. Her life reflects the contradictions inherent in Roman governance: that the state condemned what it privately commissioned and punished in public what it practised in secret.

Archaeological and Epigraphic Evidence: Tools, Residues, and Inscriptions

While literary sources provide the richest narrative accounts of poisoning in ancient Rome, they are often coloured by rhetorical, moralistic, or political aims. To supplement and test these accounts, historians and archaeologists have increasingly turned to material culture—especially the archaeological record and epigraphic evidence—for insight into Roman toxicological practices. Although direct evidence of poisoning remains rare due to the ephemeral nature of most poisons and the limitations of ancient forensic methods, a growing body of material data—pharmaceutical tools, containers, inscriptions, residue analysis, and skeletal studies—has contributed significantly to our understanding of how the Romans prepared, stored, and administered poisonous substances.

Pharmaceutical Tools and Equipment

One of the most common archaeological finds associated with Roman medical practice is the instrumentarium chirurgicum—a set of medical tools that includes scalpels, forceps, needles, and probes. Among these, several items may also have been used in the preparation and application of toxic compounds. Bronze spatulae, mortaria (grinding bowls), and small pestles and mortars were standard components of both medical and toxicological kits.

Complete sets have been excavated at military hospitals, urban domus complexes, and even tombs. For example, the physician's house at Pompeii (Regio VI, Insula 9, House of the Surgeon) contained several instruments compatible with both surgical and pharmaceutical use. While these tools do not distinguish between poison and medicine, their form and presence indicate a sophisticated pharmaceutical culture with the technical means to process toxic substances into usable compounds (Jackson, 1988).

Inscriptions and archaeological contexts sometimes clarify their use. The collyrium stamps—engraved stone or bronze stamps used to label or imprint eye salves—frequently identify toxic ingredients such as plumbum (lead), cuprum (copper), or stibium (antimony), all of which were known for their astringent or caustic properties but were potentially toxic when misapplied (Mann, 2012).

Residue Analysis and Poison Containers

Although organic poisons decompose rapidly, advances in residue analysis have allowed modern researchers to identify trace chemicals in amphorae, glass vials, and metal containers from Roman sites. In a study conducted by Bernd Herrmann and colleagues (2005), amphorae excavated from Roman burial contexts in Gaul and southern Italy were found to contain residues of opium alkaloids, digitalis, and belladonna derivatives. These findings support the hypothesis that specific containers held narcotic or poisonous preparations, possibly for therapeutic or ritual use.

In Pompeii and Herculaneum, glass phials discovered in domestic settings frequently contain residues of resins, oils, and unguents. In some cases, chemical signatures suggest the presence of known toxicants, such as aconitine or atropa alkaloids, although contamination and environmental degradation limit certainty (Scantamburlo et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the widespread use of narrow-mouthed glass containers—ampullae veneficae—suggests deliberate storage of potent substances, possibly including poisons.

Epigraphic Evidence: Inscriptions and Legal Texts

The epigraphic record preserves several references to veneficium and its prosecution. Funerary inscriptions sometimes allude to sudden or suspicious deaths, though rarely in direct terms. One tombstone from Cumae (CIL X, 3754) records that the deceased died "per insidias"—by treachery—suggesting poisoning or betrayal. Legal inscriptions from municipal laws, such as the Lex Ursonensis, contain stipulations regarding public health and the punishment of individuals who "corrupt the people with potions," using terminology akin to that found in the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis.

While few inscriptions record the identities of poisoners, some reference accusations of magia or maleficium, crimes closely associated with veneficium in both the literary and legal tradition. A lead defixio (curse tablet) from Aquae Sulis (modern Bath) curses an individual for causing harm through "drinks and decoctions" (potiones et decoctiones), hinting at a community-wide awareness of poisoning and its moral ramifications.

The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) and L’Année épigraphique (AE) both record sporadic references to cases in which poisoning is either implied or explicitly mentioned, especially in condemnations of freedwomen accused of harming their patrons or clients. These inscriptions underscore the association of veneficium with social inversion and treachery—especially when perpetrated by clients, women, or slaves.

Skeletal Evidence and Toxicological Markers

Although most poisons do not leave skeletal traces, a few mineral-based toxins, such as lead, arsenic, and mercury, can accumulate in the body and be identified post-mortem. Analyses of Roman skeletal remains from urban sites such as Herculaneum, Londinium, and Lugdunum reveal elevated lead levels consistent with chronic exposure—likely from plumbing, cooking vessels, and contaminated wine (Montgomery et al., 2010; Retief & Cilliers, 2006). While this does not constitute deliberate poisoning, it highlights the blurred line between environmental toxin exposure and intentional harm.

In rare cases, skeletal remains in funerary contexts have been subjected to strontium isotope and heavy metal analysis to test for patterns of poisoning. A notable case from a Roman villa in Gaul (discussed in Brunaux, 2009) involved a woman buried with medicinal paraphernalia whose hair and nails exhibited toxic levels of mercury—suggesting either medical self-treatment or deliberate poisoning.

The discovery of poison-related objects in temples and domestic shrines suggests a broader cultural significance beyond homicide. In some household lararia, particularly in the Vesuvian cities, miniature amphorae and labelled medicinal jars appear alongside figurines and votive offerings. This proximity suggests that toxic substances were not merely feared but could also be ritually contained, controlled, or even venerated (Bevilacqua, 2006).

So What?

From the early Republic through the height of the Empire, poison occupied a multifaceted and often contradictory role in Roman life. It was both feared and employed, reviled and institutionalised, marginalised and, at times, central to the exercise of power. The question "How did the Romans use poison?" reveals itself to be as much about Roman cultural values, social hierarchies, and legal mechanisms as it is about the substances themselves.

It was used in political assassinations, most notoriously in the imperial court, where the deaths of Claudius and Britannicus suggest a systemic use of toxicology in succession strategies. In the domestic sphere, poison was linked to anxieties about gender, servitude, and control, especially in the high-profile mass poisonings and trials that often targeted women and subaltern groups.

The Roman legal response to poisoning, enshrined in the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis, reveals the seriousness with which the crime was treated, even as it also exposes inconsistencies in enforcement. Individuals such as Locusta—simultaneously condemned as a criminal and elevated as a state asset—exemplify the Roman state's ambivalence. Poison could be criminal or curative, deviant or officially sanctioned, depending on the context and the user.

The boundaries between poison and medicine were inherently porous, as noted by Galen, Dioscorides, and Pliny the Elder. Dosage, intention, and social standing often determined whether a substance was considered therapeutic or homicidal. Archaeological finds—from surgical tools and pharmaceutical containers to chemical residues and inscriptions—support the literary image of a culture in which toxic knowledge was widespread and embedded in domestic, ritual, and medical practice.

What emerges is a picture of poison not as a marginal or anomalous phenomenon but as a deeply integrated aspect of Roman life. It was a means of social negotiation, a symbol of disorder, a method of control, and—perhaps most unsettlingly—a feature of everyday existence. The use of poison in Rome challenges modern historians to abandon simple dichotomies between crime and medicine, public and private, legal and illicit. Instead, it demands a multifaceted interpretive framework that accounts for the complexity of Roman values, the pragmatism of imperial politics, and the limitations of our sources.

Ultimately, poison in Rome was less a substance than a social category—fluid, dangerous, and always contingent on who wielded it, for what purpose, and with what degree of discretion. Its historical significance lies not only in the deaths it caused but in the fears it revealed, the laws it provoked, and the narratives it left behind.

References and Further Reading

Bevilacqua, A. (2006). Healing and religion in Roman domestic space: Lararia and the control of harmful forces. In A. Cooley (Ed.), The Afterlife of Inscriptions (pp. 142–160). University of London, Institute of Classical Studies.

Cassius Dio. (1925). Roman History (E. Cary, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Cicero. (1926). Pro Cluentio (H. Grose Hodge, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL). Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Dioscorides. (2000). De Materia Medica (L. Beck, Trans.). Olms-Weidmann.

Digest of Justinian. (1985). The Digest of Justinian (A. Watson, Trans.). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Horace. (1911). Epodes and Odes (J. Conington, Trans.). Macmillan.

Jackson, R. (1988). Doctors and Diseases in the Roman Empire. British Museum Press.

Juvenal. (1918). Satires (G. G. Ramsay, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis. (c. 81 BC). In Digest of Justinian, 48.8.3.

Livy. (1940). Ab Urbe Condita (B. O. Foster, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Lucan. (1926). Pharsalia (J. D. Duff, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Mann, J. C. (2012). Collyrium stamps: Roman medical instrument or advertising device? Britannia, 43, 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X1200013X

Montgomery, J., Evans, J., & Killgrove, K. (2010). Lead and strontium isotope compositions of human dental enamel from Herculaneum and Pompeii: Identifying migrants in the Roman Empire. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(2), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.022

Pliny the Elder. (1951). Natural History (H. Rackham, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Retief, F. P., & Cilliers, L. (2006). Lead poisoning in ancient Rome. Acta Theologica Supplementum, 7, 147–164.

Scantamburlo, E., Amadori, M. L., Sciuto, S., & Vassallo, E. (2015). Chemical analysis of ancient medicinal unguents from Pompeii: A case study. Archaeometry, 57(4), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12129

Scarborough, J. (n.d.). Poisons and poisoning in ancient Rome. Medicina Antiqua. University College London. Retrieved June 23, 2025, from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucgajpd/medicina%20antiqua/sa_poisons.html

Suetonius. (2025). The Twelve Caesars (J. Coverley, Trans.).

Tacitus. (1931). Annals (A. J. Church & W. J. Brodribb, Trans.). Macmillan.

Valerius Maximus. (1921). Memorable Deeds and Sayings (D. R. Shackleton Bailey, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Great article - really interesting!

Thanks very much.

LF

-fici = doer?