'Paganism' isn't a word you'll find used anywhere in either the Republic or the Early Empire period of Rome and was only ever used by later Christians to describe the polytheistic practices of people who were neither Christian nor Jewish.

The word 'pagan' comes from the word 'pagus' (Late Latin - 'paganus'), meaning a villager or a country dweller. It's the opposite of 'urban' and implies someone who is unsophisticated and simple. A country bumpkin, if you like.

By contrast, for the Roman polytheist, there was no word used to describe their common set of shared beliefs. For them, apart from the odd Jew or Christian or those who liked to tie themselves in philosophical knots, what they believed was as self-evident and as unassailable as understanding that the Sun came up and the Sun went down. There simply wasn't any need for a word to define what they were because they just were.

In contrast to post-Reformation Europe and, to some extent, the Empire after Constantine legitimised Christianity in 312AD, the empire was not a hotpot of religious turmoil. Whilst it was absolutely possible to have religious freedom and to make choices about what you believed in, most pagans simply never saw the need to.

So accepted was the religious status quo that there was virtually no challenge to the uniquity of the polytheistic model. And because there was no challenge, there was no competing message to spread around. As a result, there was a lack of theological literature used to explain the minutiae of the pagan belief system. Word of mouth was enough in a world where nobody ever raised any objections. This was in stark contrast to Judaism, which relied heavily on the texts for its liturgy and was something later expanded on by Christianity, which not only needed the previous texts to reinforce its Judaist origin but also to help spread the message among the pagan masses.

All paganism had to do, by contrast, is dot a few priests around the empire and let the people get on with it.

There is no continual tradition of pagan worship into modern times. The modern view of 'paganism' is largely a modern construct, invented by people who have read the Mabinogion too much and like to prance around Avebury wearing bedsheets, and whilst it extols values that hint at a long tradition, these go back only at most into the very late or post-medieval eras. There's a lack of theological literature that explains exactly what the concepts and conceits of pagan polytheism are. There's little first-hand testimony of what the relationships between humans and the gods felt like to the people who worshipped, or, come to that, how the gods felt about it all.

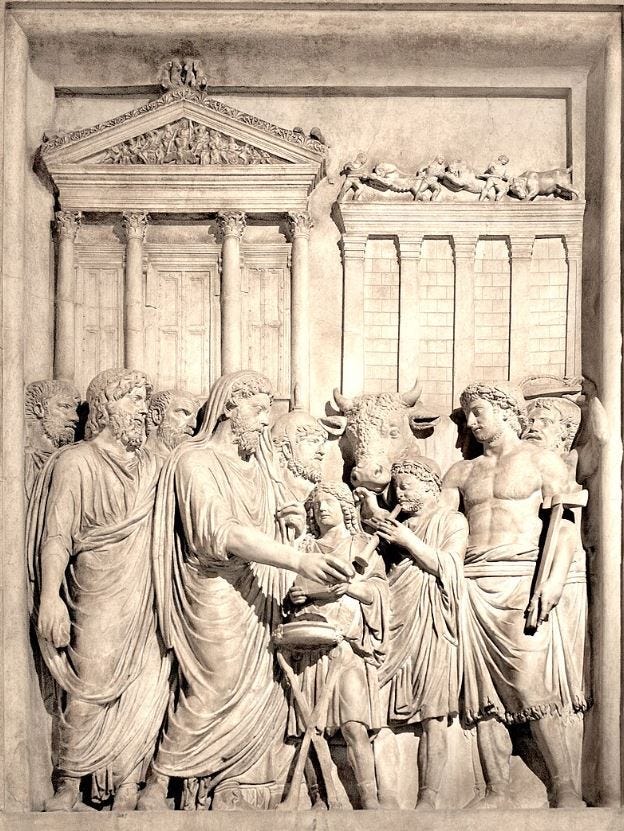

Instead, we have a series of fascinating but otherwise rather empty rituals. We might know how they worshipped, and we might know how that worship developed, but to give these rituals any sense of meaning, we have to use our imagination to flesh them out and, more often than not, because the only way we can process this relationship between humans and the gods is via the way that we understand our own relationship with modern religion (or lack of it), we sometimes let that colour our interpretations.

We divide temples up into areas that we can associate with churches. We see the word 'priest' used for a pagan and imagine that in the context of a Christian priest. We see the use of libations as corresponding to Catholic wine ceremonies. We see religious ceremonies as being like the Sabbath. We see religious feast days as Christmas. If we see elements of rituals that make us feel uneasy, we brand them perverted or Satanic.

Jewish and Christian authors of the time saw them in a similar way. Either as meaningless and empty - ritual for ritual's sake or as lewd and sinful. Even into modern times, the view of paganism as something with deviant sexual overtones has persisted. Ask most people what they think a pagan ritual is, and they'll probably say something about drunken, blood-drinking orgies. Not that there's anything wrong with that, depending on where you get the blood.

Pagan polytheistic practices came in all shapes and sizes, but whilst there were any manner of ways, none of them expressly specific, in which one could worship a certain god, the underlying belief system was universal. Nearly everyone in the ancient world was not only convinced that the gods existed and that they were surrounded by them, but they affected their lives, either directly or indirectly. In the same way that we accept that we are surrounded by germs, even though we cannot see them, and that those germs play parts in our lives, people in the ancient world accepted there were gods. In the same way, we know that if we stick to certain routines of cleanliness, we can offset the negative effects of those germs, so the polytheists knew that keeping the gods sweet was part of their routine, too.

Gods were responsible for all sorts of actions in the world, from the changing of the seasons and the cracking of earthquakes to things going missing and pots falling out of cupboards. Consequently, some of the gods were incredibly powerful (although none more so than any other), and some were comparatively weak. Whilst there wasn't necessarily a god for everything that happened, there would be a god responsible for any action not too far down the line.

What divided the gods from humans, then, were two factors. Firstly, the ability to make such actions happen, from earthquakes to pots breaking, burning bushes to sudden rainstorms. Call it a superpower if you like. Some superheroes can fly, some can turn invisible, and some can turn bendy. The second thing, also shared by some superheroes, was that the gods were immortal. Some gods may not have always existed, such as Hercules, who was born mortal, or Asclepius, the god of medicine, but none of them could cease to exist in the future. Of course, the word 'immortal' would imply that the gods were alive in the first place, and some of them, like emperors, achieved their 'immortality' only after death. Perhaps a better term would be 'permanent'. Once an emperor achieved permanence after death via the transcendence of their genius (or soul), they would then remain forever, even if the nature of their permanence could, and did, change.

Although it's possible to go online and find a list of Roman (or Greek) gods and goddesses, their number was unknown and unknowable. Especially when one began to factor in all the gods of other nations that they didn't even know about yet. The concept of a 'jealous' god who wanted none other to exist wasn't a credible option. All the gods existed, including the ones you'd never heard of yet, and if you weren't sure, you could just assume that one existed and start worshipping it. Consequently, the relationship between all these gods was also unknown, just like the relationship between all humans was unknown. It seemed unlikely, again like all humans, that all the gods even knew each other existed.

All of this diversionary wittering (and guess whose thesis was on early Christianity in the Roman Empire - not bad for an atheist) has to have a point, however, and the question at hand is a simple one - how many Roman gods were there in total?

I've already answered it, of course - nobody knows. It's unknowable simply because the concept of the pantheon necessitates a model in which the roster of gods can not only be expanded as necessary but that such expansion is a necessity of the system itself. There is an endless number of gods because that's how the polytheistic model explains itself. In the same way that some of the most banal answers to explain a monotheistic model conclude with 'God did it', the polytheistic model could explain 'who did it' by simply adding more and more gods where necessary. This constant addition of new gods never seemed, among the general population anyway, to raise much in the way of objection.

The origins of Roman gods are deeply rooted in the indigenous Italic traditions, which were later influenced by Etruscan and Greek cultures. The early Roman religion was animistic, focusing on spirits known as numina, which inhabited natural objects and phenomena. These spirits were not personified but were revered for their power over specific aspects of life and nature. As Rome expanded, it came into contact with the Etruscans, who had a more anthropomorphic view of deities. This interaction led to the adoption of Etruscan gods and religious practices, which were integrated into the Roman religious framework.

Greek mythology had a profound impact on Roman religion, particularly during the Roman Republic and Empire. The Romans identified their gods with Greek counterparts, a process known as interpretatio graeca. For example, Jupiter was equated with Zeus, Mars with Ares, and Venus with Aphrodite. This syncretism not only enriched the Roman pantheon but also facilitated cultural assimilation and political cohesion across the empire.

Syncretism played a crucial role in the expansion and evolution of the Roman pantheon. As Rome conquered new territories, it absorbed local deities and religious practices, often merging them with existing Roman gods. This practice was not merely a matter of convenience but a strategic approach to integrate diverse populations into the Roman state.

One notable example of syncretism is the Roman adoption of the Egyptian goddess Isis. Initially worshipped by Egyptian communities in Rome, Isis was gradually incorporated into the Roman pantheon, with temples dedicated to her across the empire. Similarly, the Persian god Mithras was adopted by Roman soldiers and became a popular deity among the military.

The process of syncretism was not always straightforward. Some foreign deities retained their distinct identities, while others were fully assimilated into Roman religion. This fluidity makes it challenging to determine the exact number of Roman gods, as the boundaries between Roman and foreign deities were often blurred.

In addition to the major gods and goddesses, Roman religion included a plethora of local and household deities. These gods were deeply embedded in the daily lives of Romans, overseeing various aspects of domestic and communal life. The Lares and Penates were among the most important household gods. The Lares were guardian spirits of the household and family, while the Penates protected the storeroom and ensured the family's prosperity.

Local deities, known as genii loci, were worshipped in specific regions or cities. These gods were often associated with natural features such as rivers, mountains, or forests. The worship of local deities highlights the decentralised nature of Roman religion, where each community had its own set of gods and religious practices.

The inclusion of local and household deities complicates the count of Roman gods. While some of these deities were widely recognised, others were known only within specific communities. This regional variation underscores the diversity and adaptability of Roman religion.

The imperial cult, which involved the deification of emperors, added another layer of complexity to the Roman pantheon. The practice of deifying emperors began with Julius Caesar, who was posthumously declared a god by the Roman Senate. Subsequent emperors, such as Augustus, were also deified, and their worship became an integral part of Roman state religion.

The imperial cult served both religious and political purposes. It reinforced the emperor's authority and legitimacy, while also promoting loyalty and unity among the diverse populations of the empire. Temples and altars dedicated to deified emperors were erected throughout the empire, and their worship was often combined with that of traditional gods.

The deification of emperors further expanded the Roman pantheon as each new emperor was added to the list of divine figures. However, the status of these deified emperors was not always consistent. Some emperors were widely worshipped, while others were quickly forgotten. This variability adds to the difficulty of quantifying the number of Roman gods.

Quantifying the number of Roman gods is a challenging task due to several factors. First, the Roman pantheon was not static; it evolved over time, absorbing new deities and discarding old ones. Second, the lack of a centralised religious authority meant that there was no official list of gods. Instead, religious practices varied widely across regions and communities.

The fluid nature of Roman religion also poses a challenge. Gods could be merged with foreign deities, split into multiple aspects, or even forgotten over time. For example, the god Janus, associated with doors and beginnings, had no direct Greek counterpart and was uniquely Roman. However, his worship declined over time, and he became less prominent in the later Roman Empire.

Regional variations further complicate the count. While some gods, such as Jupiter and Mars, were worshipped throughout the empire, others were known only in specific regions. The worship of local deities and household gods adds another layer of complexity, as these gods were often not included in official records.

As monotheism eventually began to replace the polytheistic model across the empire (or what had been the empire), so, particularly with Christianity, it was faced with the problem of what to do with all these thousands of minor gods and, in particular, the localised cult worship of them. Christianity needed a uniformity of message that polytheism could skip by just adding more gods to the list, and the best way of doing so was to alter the status of these minor gods and, therefore, of the shrines associated with their cult and call them something else. If Christianity could keep these sites 'holy' but replace the 'godlike' status of the associated figure with another level of divinity altogether, then the new religion could simply step into the shoes of the old quite seamlessly. If anything, the greatest trick that Christianity pulled when it came to expansionism was to fully embrace what might be called the Time of the Saints.

But that's for another day.

References

Beard, M., North, J., & Price, S. (1998). Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History. Cambridge University Press.

Rüpke, J. (2007). Religion of the Romans. Polity Press.

Turcan, R. (2000). The Gods of Ancient Rome: Religion in Everyday Life from Archaic to Imperial Times. Edinburgh University Press.

Warrior, V. M. (2006). Roman Religion: A Sourcebook. Focus Publishing.

Thanks for reading! If you’re stuck for a gift for a lost loved one, or for someone you hate, or if you have a table with a wonky leg that would benefit from the support of 341 pages of Roman History, my new book “The Compendium of Roman History” is available on Amazon or direct from IngramSpark. Please check it out by clicking the link below!