The Romans loved nothing more than a bit of petty bureaucracy, and of all the petty bureaucratic exercises in which they revelled, none was as exciting to the box-ticking Roman psyche as the census.

Of the censuses they held, perhaps the most famous is the one that, according to the account in the New Testament, normally attributed to the author (or authors) that we call 'Luke', happens at the time of the birth of Jesus. There are two accounts of the birth of Jesus in the New Testament - Matthew and Luke - and only Luke has the census that forces Joseph and the pregnant Mary back to Bethlehem:

"And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be taxed. (And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria.) And all went to be taxed, every one into his own city."

(Luke 2. 1-3)

The Cyrenius of Luke 2 is Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, who was appointed the legate governor of Syria in AD 6, with explicit instructions for dealing with the aftermath of the removal of Archelaus (son of Herod) from his position as ethnarch of Judea and preparing the remains of his realm ready for incorporation into the Empire as a full province.

Matthew's account of the birth - the one with the Magi and all that - happens when Herod is still alive, so at least ten years earlier, but that's another matter entirely. Safe to say that the census of Quirinius can be safely dated to AD 6 in the archaeological record.

So Quirinius holds the census with the apparent goal of collecting taxes, and this is a little misleading as what, if anything, he would have been collecting would be more correctly identified as a tithe. Quirinius himself wouldn't have been responsible for collecting this money and neither did the Romans wait until the census in order to collect it.

By the time of the census of Quirinius, the collection of taxes in the provinces was the remit of people referred to in the records as 'tax farmers'. These were mostly petty officials and rich locals who, at first, would have been compensated for their time. But later on, they were expected to collect and remit the money as part of their civic duty, which sounds like a tedious imposition on a posh bloke's time, and was, but was made all the more terrifying for these men when it became apparent that they, personally, were responsible for handing over the money.

Another fun part of Roman bureaucracy was the apparent terror it could generate at just about every level below the inner circle of the emperor and his family.

The tax farmers ultimately became fully responsible for supplying the amount of money from the provinces that the central fisc demanded. How they went about getting it was their own problem. If the fisc asked for 3 million sesterces, then you, personally, had to pay it. This was fine when times were good, but in times of famine or war, when the demands couldn't be met by squeezing the local peasants, many of these tax farmers simply chose to run away and hide rather than face the wrath of central command:

"The governor of the province shall see to it that the decurions who are proved to have left the area of the municipality to which they belong and to have moved to other places are recalled to their native soil and perform the appropriate public services...."

(Justinian, Digest L.ii)

As such, there was no sympathy to be had should the tax farmers turn up at the governor's palace, cap metaphorically in hand, complaining that they held the peasants by the ankles and gave them a good shake, but all they got was two goats and a bucket full of barley. Central HQ wanted its money, and it wanted it from YOU. How you got it was your problem.

Taxation, then, had to be about more than just shaking peasants, and the most profitable way of generating taxes was to levy a charge on goods as they moved around the Empire. Everyone from grand merchants to humble shepherds brought their wares into the city to sell, and it was at the gatehouses that the fortunes that kept the tax farmers' necks connected to their heads were generated.

A census was never really about taxation, even if it did give you a handy list of where people were, should you wish to go round to their hovel and shake them for a bit. The census of Quirinius, for example, despite what Luke says, could never have been about taxation for the simple reason that it was taken by the army, and the army was not only exempt from taxation but was never used to collect taxes. If the tax farmers needed some heavies to strong-arm people or to guard their money, they were expected to hire their own (Just. Dig. iv. 1-2).

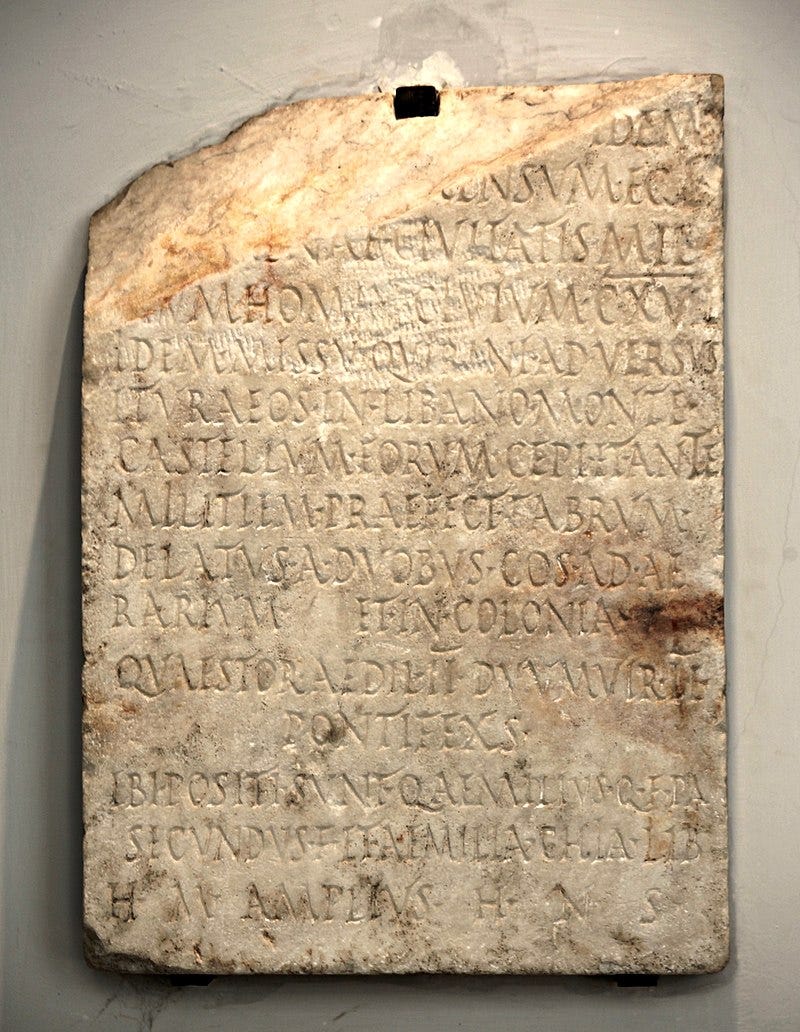

The funerary inscription of Quintus Aemilius Secundus, prefect of cohors II Classica, describes how he took the census at Apamea (in Syria now, but then in Judea) at the command of Quirinius, meaning that the census of AD 6 was, despite what Luke says, never about taxation but, more likely, about reckoning the province prior to absorption and also about moving groups of irate Jews about the place so they would stop killing each other - one of the reasons Archelaus had been deposed in the first place.

Each municipality could raise its own levies on goods depending on a variety of factors, including edicts right from the emperor himself. These charges might fluctuate depending on what facilities were available in the municipality and, obviously, the more attractive a town was to visit, the more the taxes went up, both to pay for the services provided and to reflect the status of the town.

A tariff (CIL III 4508) was posted at the town of Zarai, at the site of present-day Aïn Oulmene, Algeria, in what was then Roman Numidia. Dated to AD 202, in the reign of Caesar Lucius Septimius Severus Augustus Pius - Septimius Severus to you. It is a new set of charges given after the removal of the local cohort (although which one isn't clear), which would suggest that charges have been lowered to reflect the loss of status following the removal of the soldiers and, naturally, all the money they carried with them.

Interestingly, the charges are not calculated ad valorem - they are flat charges per item.

Regulation for tax per head

Slaves, each 1.5 denarii

Horse, mare 1.5 denarii

Mule 1.5 denarii

Ass, cow (or bull) .5 denarius

Pig 1 sesterce

Suckling pig .5 "

Sheep, goat 1 "

Regulations for imported clothing

Dinner mantle 1.5 denarii

Tunic 1.5 "

Blanket .5 denarius

Purple cloak 1 denarius

Regulation on hides

Hide, dressed .5 denarius

Hide, with hair .5 sesterce

Sheepskin .5 "

Supple saddle hides, per 100lbs ......

Coarse hides, per 100lbs .5 denarius

Glue, per 10lbs .5 sesterce

Sponges, per 10lbs .5 "

Miscellaneous custom regulations

Wine, per amphora; garum, per amphora 1 sesterce

Dates, per 100lbs .5 denarius

Figs, per 100lbs ...

Green peas in the pod, per 10 modii* ...

Nuts, per 10 modii ...

Resin, pitch, alum, per 100lbs ...

Iron ...

(The rest is lost)

*A modii was a measure of about 8.7 litres, or 2.3 gallons.

References and Further Reading

Justinian. (533). Digest. (L.ii; iv. 1-2).

Luke. (n.d.). The Holy Bible, King James Version. (Luke 2:1-3).

Quintus Aemilius Secundus. (n.d.). Funerary Inscription. CIL III 6687

Roman Tariff of Zarai. (202 AD). Epigraphic Inscription. CIL III 4508

I've just finished the book, at about 4 AM. Loved the overall tone; you can be up there with Suetonius for snark! And I learned things too.

Will message you a few notes.