How Realistic Were Roman Statues?

When a reader asks a question about Roman iconography, it is all someone like me can do to resist the temptation to adopt the air of an excited puppy, crack my fingers and begin work on an expansive tome, delving deep into the musky waters of the complexities of ancient portraiture. Many years ago, back in the days when, like Julius Caesar, I didn't gaze forlornly into the amber haze of a polished bronze mirror and wonder where my hair went, I wrote my thesis on the subject of iconography in the first century AD. I live for this sort of thing. However, the specific question being asked was about how realistic Roman iconography, specifically statues, was. Did they really look like that? So, somewhat reluctantly, I must temper my ambitious and verbose streak and try to bring this article in somewhere south of a billion words.

As such, I'm going to skip over a lot of the nuances of iconography, the power-plays being represented by various images, how emperors would use iconography as propaganda and all the juicy stuff, and instead chew on the marrow of the question at hand. Did they really look like that?

Roman sculptors were renowned for their ability to craft lifelike and detailed depictions, a skill that set them apart from their Greek predecessors, who often idealised their subjects. However, the question of how realistic these portraits truly were remains complex, particularly when compared to written descriptions of figures such as Julius Caesar.

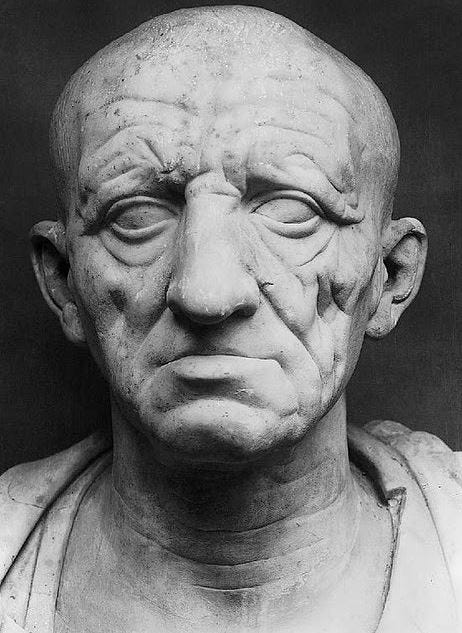

Roman portraiture emerged as a significant art form during the Republic, characterised by the veristic style. Verism emphasised hyper-realistic details, showcasing every wrinkle, sag, and blemish to convey an individual's age and wisdom. This stylistic approach was particularly prominent in the busts of senators and other elite figures, as physical imperfections were seen as marks of a life dedicated to public service and moral virtue (Zanker, 1988). However, this tendency shifted under the Roman Empire when emperors began to use portraiture as a tool for propaganda, blending realism with idealisation to convey authority and divine favour.

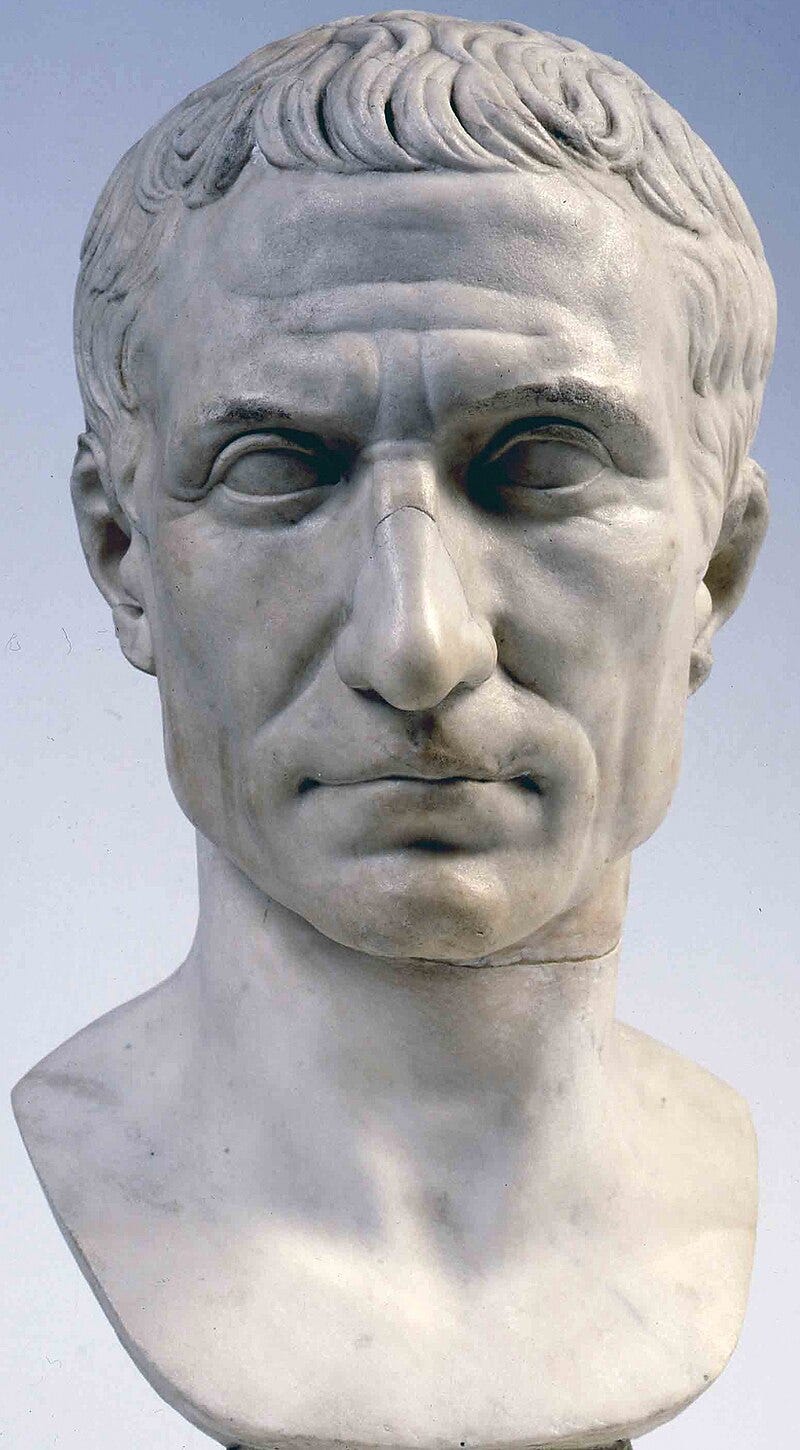

Julius Caesar provides an intriguing case study in the realism of Roman portraiture. Caesar's physical appearance is described in several ancient texts. Suetonius, in his Lives of the Caesars, notes: "He is said to have been tall, fair of complexion, shapely of limbs, somewhat full-faced, and with keen black eyes. He was also said to have been excessively concerned about the arrangement of his hair, and the baldness which his friends often ridiculed" (The Twelve Caesars, Divus Julius, 45). Despite these descriptions, surviving portraits of Caesar made during his lifetime, such as the Tusculum bust, depict him with a relatively full head of hair and an air of dignity that downplays his physical vulnerabilities. The Tusculum portrait is famous for clearly showing the apparent cranial deformity that Caeasar may or may not have suffered from. These discrepancies suggest that sculptors prioritised projecting an image of strength and leadership was just as important as a strict adherence to reality. The deep lines on his neck are very distinct and give the impression of a man who has spent a long time outdoors, in this case specifically on campaign rather than swanning about eating dormice and having baths.

Compare it with the Chiaramonti bust, a posthumous portrait with a proud head of hair and a normal head shape. It is the same man, but a much more sympathetic version of him.

The tension between written descriptions and sculptural depictions is not unique to Caesar. Emperors frequently used portraiture to craft their public personas. Augustus, Caesar's adopted heir, offers a striking example of this phenomenon. Ancient sources like Cassius Dio describe Augustus as a man of average height with a calm demeanour and blemished skin: "He was said to have spots on his chest and belly and suffered frequent illnesses" (Roman History, 56.30). However, the iconic Prima Porta statue presents a youthful and godlike leader, his visage free of imperfection. The statue's idealisation aligns with Augustus' political agenda, emphasising his role as a divinely favoured and eternal ruler.

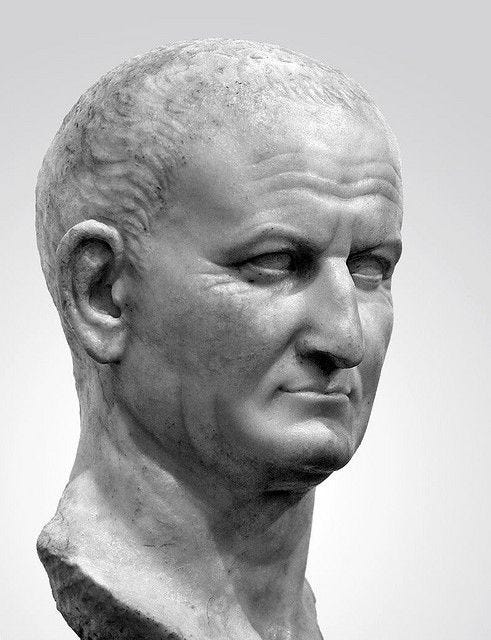

Another compelling comparison can be made with the emperor Vespasian, whose reign marked the end of the civil wars of AD 69. Vespasian's coinage and sculptures, such as the famous bust in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, reflect a return to a more veristic style. Ancient historians like Tacitus describe Vespasian as a man of modest and unpretentious appearance: "He had a cheerful expression and was generally unconcerned with his appearance, though he was balding and somewhat dishevelled" (Histories, 2.80). His portraits corroborate this characterisation. His deep-set wrinkles, sagging jowls, and weathered expression convey the image of a pragmatic and experienced leader, aligning with his reputation as a restorer of stability. The sources tend to suggest that Vespasian was rather charmless and crass, but what they're suggesting is not a man who wasn't charismatic but one who didn't bother himself much with the normal niceties of elite Roman society. He wasn't a man who ate his cucumber sandwiches with the crust cut off, if you get my drift. That doesn't mean he wasn't funny and charming - he's a dab hand with a laconic one-liner - just that the ideal of 'charming' they are describing didn't include making jokes about urinals. Even if you knew nothing about Vespasian whatsoever, you could take these two snippets of information - he was a cheerful chap with a quick wit and blunt manner - take a look at the bust of him and then form a whole opinion about what sort of a chap Vespasian was. And chances are, you'd probably be right, too. That's the power of iconography.

This interplay between realism and idealisation continued throughout the Roman Empire, adapting to the needs of each emperor's reign. The portraits of Hadrian, for example, reflect his embrace of Greek culture, with a distinctively Hellenised beard that set him apart from his clean-shaven predecessors. While ancient texts like the Historia Augusta describe Hadrian as physically robust and energetic: "Hadrian was said to have a lively complexion and an inquisitive nature, constantly seeking knowledge" (Life of Hadrian, 20), his statues portray him with a serene and contemplative expression, emphasising his intellectual and philosophical interests over his physical attributes.

While Roman artists were undoubtedly skilled at capturing the physical likeness of their subjects, they were also tasked with conveying abstract qualities like virtue, authority, and divine favour. These competing priorities often resulted in portraits that blended realism with idealisation. For example, Commodus, the infamous son of Marcus Aurelius, commissioned portraits that presented him as Hercules, complete with a lion's skin and a club, underscoring his claim to divine strength and heroism (Hekster, 2015).

The question of realism also extends to non-imperial portraiture, which offers additional insights into Roman artistic practices. Funerary portraits from the Fayum region of Egypt, created during the Roman period, are strikingly lifelike and often compared to modern photographic realism. These portraits, painted on wooden panels, capture individual features with remarkable accuracy, from the texture of the skin to the shine in the eyes. While these works served a different purpose than imperial statues—namely, to commemorate the deceased—they demonstrate the technical skill and attention to detail that Roman artists could achieve when unencumbered by political or propagandistic concerns (Walker, 2000).

In evaluating the realism of Roman portraiture, it is essential to acknowledge the cultural and political context in which these works were created. Emperors used their images to communicate specific messages to their subjects, whether it was Augustus' divine authority, Vespasian's pragmatism, or Commodus' hubris. While written descriptions provide valuable clues about the physical appearance of historical figures, they are often filtered through the biases of their authors, just as sculptural depictions are shaped by the agendas of their patrons.

Roman statues occupy a space between realism and idealisation. While sculptors demonstrated exceptional skill in rendering lifelike details, these portraits were rarely ever unvarnished depictions of their subjects. Instead, they were carefully curated images designed to convey messages of power, virtue, or divine favour. Comparisons with written accounts reveal that Roman portraiture was as much about shaping perceptions as it was about reflecting reality, illustrating the sophisticated interplay between art, politics, and identity in ancient Rome.

To answer the question - yes. That's pretty much exactly what they looked like.

References

Dio, Cassius. (2006). Roman History (E. Cary, Trans.). Loeb Classical Library.

Hekster, O. (2015). Commodus: An Emperor at the Crossroads. Brill.

Suetonius. (1998). The Twelve Caesars (R. Graves, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Tacitus. (2009). The Histories (A. J. Woodman, Trans.). Hackett Publishing.

Walker, S. (2000). Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. The British Museum Press.

Zanker, P. (1988). The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (A. Shapiro, Trans.). University of Michigan Press.

Thanks for reading! If you’re stuck for a Christmas gift for a loved one, or for someone you hate, or if you have a table with a wonky leg that would benefit from the support of 341 pages of Roman History, my new book “The Compendium of Roman History” is available on Amazon or direct from IngramSpark. Please check it out by clicking the link below!

Maybe it's because this was the subject of your long-ago thesis (are you a reincarnated roman scholar or something?) this is a really good essay that shows a deep knowledge of the subject, a subject which I'd never really bothered to think about. I wish it were possible to see those funerary paintings you mentioned. It's clear that Roman artists were fabulously skilled. This makes me think how naive we are today about our own legacy. Digital images last only as long as the electronic platform they are displayed on. Printed photos might last a couple centuries if we're lucky. No visual references will be left of our era two thousand years hence unlike those of the Roman world. None of our photoshopped portraits will be resurrected. That's what you're saying about these brilliant roman sculptors (do any of their names survive)? They were able to do some light photoshopping in marble. (Marbleshopping?) These photos are really good too, the lighting on all four of these pictures is excellent. I love the first picture which shows to what degree objectivity was prized by this civilization. Just within the last few years I have noticed a powerful disdain for objectivity developing in our own time. I wish it was only in our images. I think it's becoming a way of thinking about things as well. (Mentalshopping?) Or maybe it's just that I'm noticing it more these days.