I'm a country boy. When I'm not riding around on a tractor, or a shire horse, or whatever it is country boys do these days, chewing on a length of straw and burying hitch-hikers on remote parts of my farm, like normal, everyday country folk, I'm to be found in a field somewhere taking in great, long, lungfuls of meadow fresh country air.

Having said that, of course, the countryside smells mostly of shit, mud, dank river water and desperation. You can tell tourists in my neck of the woods because they're the ones staggering around, their heads giddy with excess amounts of linen-scented air. They stand on cliffsides, drinking in the salty ozone pong of the ocean as seals gambol in the bay below them. All that sort of thing.

To us simple country folk, the countryside smells mostly of nothing at all because, of course, we're used to it, and when we do sniff the air and sigh with satisfaction at the familiar odour of home, normally after a few days away somewhere with trains, roads and electricity, the smell we find reassuring is wet-oak, methane-rich fog of cow shit.

Cow shit is, without a doubt, the finest smell on God's tractor-rutted muddy earth.

When I was growing up, there was an old boy who worked on our remote farm in the wild west of Wild West Wales, who went by the rather magnificent name of Eirawyn. The name 'Eirawyn' consists of two parts - 'Eira', which means 'snow' in Welsh and 'wyn', which means 'white'. He was literally called Snow White.

He was the sort of man who looked like he was 58 years old from the age of 28 until he died at some incredibly old age, and he was born on the farm, lived next door all his life, and was made from the same fabric that wove the grass together and burbled in the rivers.

He had lived in the same valley all his life, and the furthest he had ever travelled was Haverfordwest, back in the 1960s, and one day we took him to Cardiff, the capital city of Wales, in his 35-year-old suit and Tidy Shoes.

He spent the whole day bewildered, not at the noise or the people, which he seemed to find rather interesting, but mostly at the kaleidoscope of smells.

When I asked him what he thought of Cardiff, it was only the second time I ever heard him swear, which, for a Welshman, shows extraordinary restraint. The first time I heard him swear was the first time (of three) that he saved me from drowning in the river, but of Cardiff, he said, simply:

"It smelled like shit."

For someone who spent most of his life smelling of actual cow shit, that was quite the critique.

Cities smell. Some of them have unique smells. Some of them smell awful, and some of them smell like a souk in Zanzibar. But they all smell. And so did ancient Rome. But of what?

The study of ancient Rome often focuses on monumental architecture, political structures, and literary achievements, yet an equally significant dimension of Roman life remains less frequently considered: the sensory environment. Of these senses, smell was a constant and unavoidable part of daily experience. In a pre-industrial city of close to one million inhabitants by the early imperial period (Morley, 2015), odours pervaded every aspect of life, from the stench of open sewers to the fragrance of imported spices and perfumes. Reconstructing what Rome smelled like is more than a matter of curiosity; it reveals how Romans lived, how they perceived their environment, and how sensory experience shaped the social and cultural world of the ancient city.

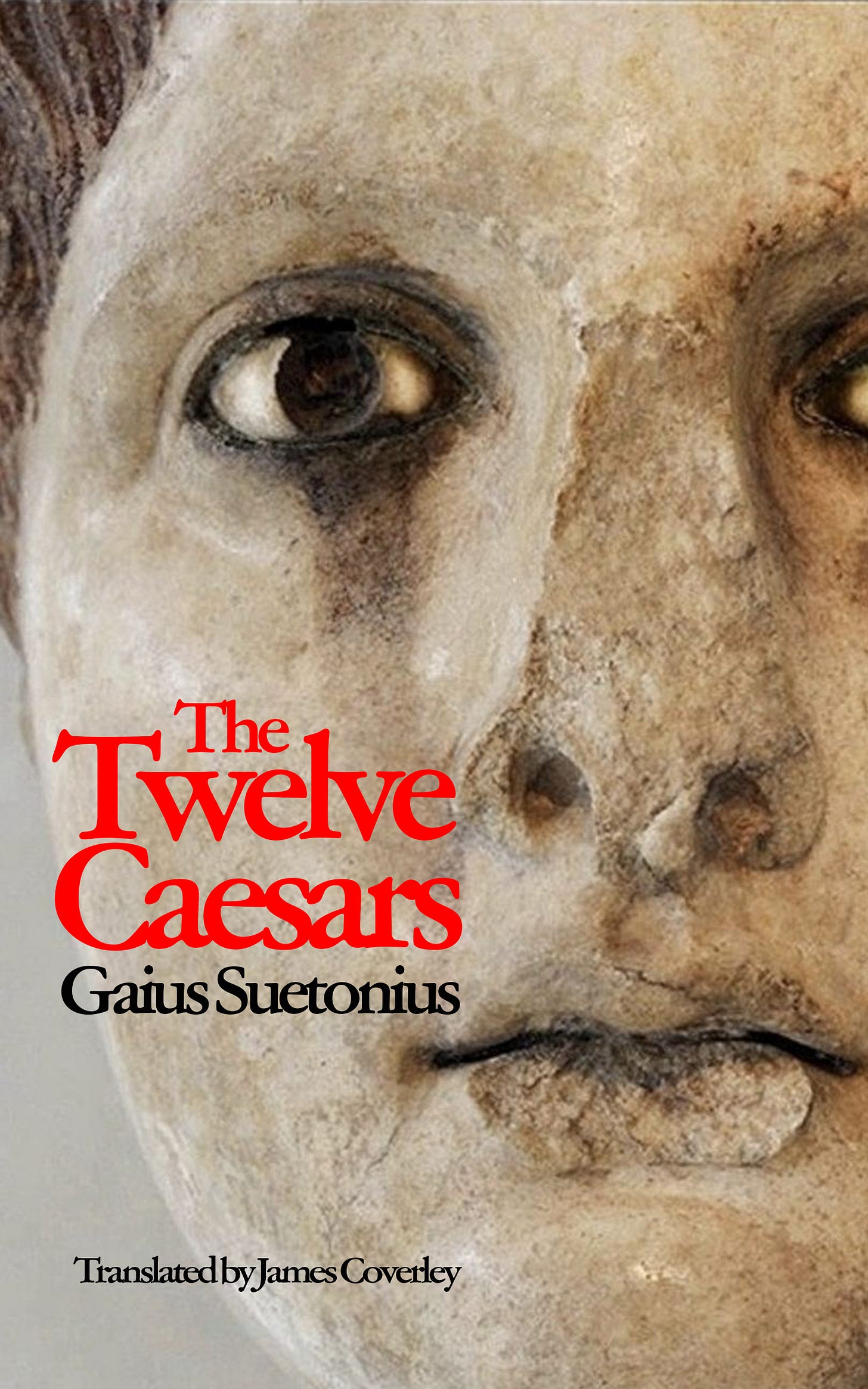

Unlike sight or sound, smell resists easy preservation in the historical record. Archaeology can recover traces of burned materials, residues of oils, and even calcified remains in drains, while literary sources preserve descriptions, sometimes satirical, sometimes moralising, of odorous spaces. Suetonius, for example, comments on the smells associated with imperial banquets and excesses, giving us glimpses of olfactory luxury (Coverley, 2025). Martial, Juvenal, and Seneca likewise remark on the malodorous realities of Rome's dense urban life. Medical authors such as Galen discussed the effects of smell on health, while inscriptions occasionally referenced perfumes and oils. Together, these sources allow us to catch the powerful olfactory whiff of Rome.

The streets of ancient Rome were narrow, winding, and often crowded, shared by pedestrians, animals, vehicles, and merchants, creating a dense layering of smells. The presence of livestock, particularly horses, mules, and oxen, added a constant manure scent, compounded by the lack of systematic street cleaning outside of elite-maintained thoroughfares (MacDonald, 1986). Archaeological excavations of the city's main streets, such as the Via Sacra and the areas surrounding the Forum Romanum, reveal evidence of repeated trampling and wear consistent with heavy foot and cart traffic, but also channels and drains intended to carry waste away, though they were frequently overwhelmed during high traffic periods (Melis, 2001).

Markets were focal points of both commerce and odour. Food sold in the streets included fish, meat, vegetables, and garum, the fermented fish sauce ubiquitous in Roman cuisine. The sale of fresh fish at markets, as described by Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia 32.20), would have produced potent odours, especially in summer heat. Archaeological finds of fish bones, oyster shells, and storage amphorae in the Forum Boarium and Macellum suggest that these areas would have had a particularly pungent atmosphere. Similarly, meat stalls contributed a combination of animal smells and smoke from fires used to prepare or cook food, further layering the sensory environment. The Roman street, therefore, was an immersive olfactory space, alternating between offensive and appetising stimuli depending on the location and time of day.

Street cleanliness and waste management had a significant influence on odours. Rome's sewer system, most notably the Cloaca Maxima, drained rainwater and waste from private homes and public latrines into the Tiber (Hopkins, 2003). Yet during periods of heavy use or maintenance neglect, waste overflowed into streets, intensifying malodour. Inscriptions and epigraphic evidence demonstrate the city's municipal awareness of this problem, including fines for littering and regulations on the disposal of refuse (Epigraphic Database Roma). Despite these measures, it is evident that ordinary Romans regularly encountered an olfactory environment shaped by both human activity and infrastructural limitations.

Simultaneously, the streets were scented with pleasant odours, particularly in commercial districts selling spices, perfumes, and baked goods. Archaeological studies of ceramic vessels and residue analysis from markets such as the Trajanic Forum reveal the presence of imported spices, including pepper, coriander, and cinnamon (Morley, 2015). Merchants selling these goods would have contributed subtle, fragrant overlays to the more pervasive urban smells, producing a sensory mosaic that reflected both abundance and decay.

Public baths (thermae) were central to Roman social life, offering spaces not only for bathing but also for exercise, relaxation, and social interaction. The olfactory environment of these spaces was markedly different from that of the streets and marketplaces, though no less complex. Baths combined the smells of water, sweat, oils, perfumes, and, at times, the less pleasant odours of human bodily effluvia. Archaeological studies of thermae such as the Baths of Caracalla and the Forum Baths at Pompeii reveal large, open halls with hypocaust systems, which would have retained and radiated the smells of heated air and humid spaces (Yegül, 1992).

The use of oils and strigils, tools for scraping the skin, contributed both to the ritual of bathing and to the olfactory landscape. Roman authors, including Seneca, remarked on the characteristic scents of bathhouses, noting that the mingling of oils, sweat, and water produced a distinct smell that could be simultaneously pleasant and pungent depending on personal hygiene and crowding (Seneca, Epistulae Morales 64). Perfumed oils and aromatic unguents were commonly used by bathers and by attendants to enhance the olfactory experience. Residue analysis from ceramic oil vessels and amphorae confirms the use of substances such as olive oil, myrrh, and cedarwood oil, sometimes mixed with fragrant herbs (Hope, 2002).

Baths also included areas for exercise (palaestrae) where vigorous physical activity contributed to an accumulation of sweat and dust. The combination of warm, humid air with the scents of exertion created an environment that could quickly become overpowering in heavily frequented facilities. Ventilation through windows and doorways helped mitigate the strongest odours, but the sheer number of bathers ensured that the smell of human exertion remained a persistent feature of the sensory experience.

Water itself was a defining element of the bathhouse environment. Heated pools and cold plunge baths (frigidaria) emitted subtle mineral and earthy aromas, depending on the source of the water. The construction of aqueduct-fed systems, such as those supplying the Baths of Trajan, provided a relatively clean water supply, though the presence of organic matter and the warm temperatures could contribute faintly to the olfactory complexity (Hodge, 1992). Although the water supply system in Rome prided itself of keeping water constantly flowing through the city, the presence of so much water - millions of gallons at a time - made it a very damp place, and the resulting build-up of organic material associated with the presence of water, such as moss, contributed to the smell. Parts of the city must have seemed like a dank cave at times.

Finally, the social and cultural practices associated with baths shaped smell in indirect ways. Scented oils, aromatic powders, and incense burners were employed to elevate the bathing experience.

Roman latrines and toilets were among the most notorious contributors to the city’s olfactory environment. Public latrines (foricae) were widespread, often situated near markets, forums, and bathhouses to serve the dense urban population. Archaeological evidence, including excavations at Ostia Antica, Pompeii, and Rome itself, reveals stone or wooden seating with channels beneath to carry waste away, often emptying into the Cloaca Maxima or nearby drains (Lancaster, 2005). The design of these facilities, rows of seats over continuously flowing water, indicates an understanding of the need to remove waste efficiently, yet the high traffic and limitations of sewage technology meant odours were unavoidable.

Literary sources frequently reference the pungency of latrines. Juvenal, in his satires, critiques both public hygiene and the odours emanating from communal toilets, noting the indignities suffered by ordinary Romans in these spaces (Juvenal, Satire 3.45–60). Similarly, Pliny the Elder comments on the presence of latrines in villas and cities, describing measures taken to control the spread of noxious smells (Naturalis Historia 36.3). Even within private residences, latrines often vented directly into street drains or cesspits, contributing to a persistent background of urban odour.

Despite these challenges, Romans employed strategies to manage unpleasant smells. Epigraphic evidence, including inscriptions dedicated to deities associated with sanitation, suggests ritualised attention to hygiene and, indirectly, to olfactory control (Epigraphic Database Roma). Certain latrines were equipped with channels carrying scented water or with placements of aromatic herbs to reduce offensive odours. Archaeological studies of residues in some facilities indicate the presence of substances such as crushed myrtle, pine resin, or other fragrant plant matter, suggesting deliberate attempts to improve the sensory environment (Hope, 2002).

Moreover, the proximity of latrines to other public spaces such as forums or markets would have influenced the broader olfactory experience of the city. Even when physically separated, wind patterns and the movement of crowds meant that smells from waste facilities permeated surrounding streets, forming a continuous olfactory backdrop for daily Roman life. The contrast between the utilitarian yet odorous latrines and the fragrant oils of the baths or markets demonstrates the extremes of the Roman sensory environment.

Taverns (cauponae), bars (popinae), and inns (tabernae) represented another distinctive olfactory dimension of Roman urban life. These establishments were hubs of social interaction, food preparation, and lodging, combining the scents of cooking, spilt wine, smoke, and human presence. Archaeological evidence from Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Ostia Antica indicates that many such spaces were small and densely furnished, often with hearths or cooking areas directly adjacent to seating spaces, concentrating odours within limited interiors (Dobbins & Foss, 2007).

Food preparation was a primary source of aroma. Common fare included bread, stews, fish, and roasted meats, often cooked over open fires. The combination of burning wood, hot oils, and the foods themselves produced a layered olfactory environment, simultaneously inviting and overpowering. Residue analysis from ovens, amphorae, and cooking vessels confirms the frequent presence of grains, legumes, and fish products, demonstrating how culinary practices directly shaped smell (Morley, 2015).

In addition to food, spilt wine, beer, and other beverages contributed to the scentscape. Fermentation aromas could permeate the air, especially in inns where storage jars and barrels were kept on-site. Epigraphic evidence from commercial inscriptions indicates the sale of wine, garum, and other aromatic goods in tabernae, further contributing to the sensory complexity of these establishments (Epigraphic Database Roma).

Human activity was another key factor. Taverns and inns accommodated diverse populations, from travelling merchants to local labourers. The mingling of body odour, sweat, and smoke created a persistent olfactory presence. Authors such as Martial and Juvenal occasionally satirise these spaces, noting their smells in humorous or critical commentary, which indirectly confirms their prominence in daily experience (Martial, Epigrams 4.1; Juvenal, Satire 1.60–75).

Some inns and higher-end taverns attempted to improve the olfactory environment. Archaeological evidence suggests the use of incense, aromatic herbs, or perfumed oils to mitigate unpleasant smells, particularly in establishments catering to wealthier patrons. For example, residue analysis in select Pompeian tabernae indicates traces of myrtle and pine resin, likely intended to mask cooking odours and the presence of animals such as cats or dogs kept for pest control (Hope, 2002).

Private residences in Rome, ranging from modest insulae to expansive domus, offered a markedly different olfactory experience compared with public streets, baths, or taverns. The diversity of smells within these spaces reflected architectural layout, household activities, social status, and deliberate scent management. Archaeological excavations in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the city of Rome itself provide substantial evidence of domestic spatial organisation, kitchen structures, latrines, gardens, and courtyards, all of which contributed to the internal olfactory environment (Coarelli, 2014).

In the homes of ordinary Romans, cooking was a primary source of aroma. Hearths and small kitchen areas (culinae) generated smells from boiling pulses, baking bread, and roasting meat or fish. Residue analyses of cooking vessels and ovens confirm that common ingredients included grains, legumes, olive oil, and fish products, all of which produced distinctive odours (Morley, 2015). The proximity of kitchens to living areas in smaller dwellings meant that these smells permeated the interior, creating a continuous olfactory backdrop.

Gardens and atria introduced natural fragrances into the home environment. Plants such as roses, myrtle, and laurel, often grown in peristyles or atria, emitted floral and herbal aromas, providing both aesthetic and olfactory pleasure. The layout of these spaces facilitated air circulation, allowing fragrant breezes to mingle with domestic smells, while fountains and water features contributed subtle aquatic scents. Inscriptions and literary sources occasionally mention ornamental gardens and their role in providing pleasant fragrances, particularly in elite houses (Pliny, Naturalis Historia 15.24).

Perfumes, incense, and aromatic oils were central to the sensory design of palaces. Archaeological analysis of amphorae, unguentaria, and residue in elite residences reveals the use of substances such as myrrh, frankincense, cedarwood, and rose oil (Hope, 2002). These scents were deployed in a variety of contexts: ritual purification, personal grooming, and ambient scenting of reception areas. Here, the goal was not just to mask smells, but to present aroma as part of the luxury and might of Roman elite power. When Elagabalus had their guests strewn with a rain of rose petals, the aroma of the sensation was as much a display of absolute opulence as the sight of it. What greater 'waste of money' could there be than simply making things smell pretty?

The River Tiber was both a vital resource and a persistent contributor to the stench of ancient Rome. It served multiple functions: as a source of water, a transportation route, and a conduit for waste disposal. Archaeological and literary evidence indicate that the Tiber’s proximity had a significant impact on the smells experienced by Romans in adjacent streets, markets, and residential areas.

One major factor was pollution. The river received runoff from streets, latrines, and industrial sites, carrying organic matter, human waste, and animal by-products into its waters. Suetonius, in discussing urban life, notes the unsanitary conditions associated with dense habitation and watercourses, though he primarily focuses on the imperial perspective of city management (Coverley, 2025). Pliny the Elder provides further commentary on the consequences of contaminated water sources for both smell and public health, describing the odour of stagnant or polluted water as a concern for residents (Naturalis Historia 36.3). Archaeological surveys of the Tiber’s banks reveal sediment layers containing animal bones, pottery, and other urban debris, which would have contributed to a pervasive riverside stench (Melis, 2001).

Seasonal changes and water flow also influenced olfactory conditions. During dry periods, slower-moving sections of the river could stagnate, increasing the intensity of foul odours from accumulated waste. Conversely, higher flows during rains could dilute odorous materials and carry them downstream, dispersing the smell across a wider area. The interaction between wind, urban architecture, and the river's movement created a dynamic olfactory environment in riverside districts.

It's clear from the sources that Romans were acutely aware of smell, deploying strategies to enhance pleasant aromas and mitigate horrid ones. The use of oils, incense, and aromatic plants demonstrates the cultural significance of scent as a medium of social signalling, luxury, and personal hygiene. At the same time, the unavoidable malodours of urban life, whether from waste, animals, or human density, remained a constant feature, forming a backdrop against which all different sensory experiences unfolded.

It is clear that smell was integral to the urban experience, shaping perceptions of space, status, and community. The city was not only seen and heard but also continuously smelled, a dynamic, multifaceted environment that combined natural, human, and artificial olfactory elements.

Eirawyn would probably have summed it up as smelling a bit like shit. And roses.

References and Further Reading

Coarelli, F. (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Coverley, J. (2025). The Twelve Caesars (J. Coverley, Trans.). The Cych Press.

Dobbins, J. J., & Foss, P. W. (2007). The World of Pompeii. Routledge.

Hope, V. M. (2002). Roman Baths and Bathing: Proceedings of the First International Bath Conference. Oxbow Books.

Hodge, A. T. (1992). Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply. Duckworth.

Lancaster, L. (2005). Pompeii: Daily Life in an Ancient Roman City. Routledge.

MacDonald, W. L. (1986). The Architecture of the Roman Empire, Volume II: An Urban Appraisal. Yale University Press.

Melis, L. (2001). “Urban Drainage in Ancient Rome.” Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 45–72.

Morley, N. (2015). Metropolis and Hinterland: The City of Rome and the Italian Economy 200 BC–AD 200. Cambridge University Press.

Pliny the Elder. (n.d.). Naturalis Historia (translation consulted for evidence).

Seneca. (n.d.). Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium (translation consulted for evidence).

Yegül, F. K. (1992). Baths and Bathing in Classical Antiquity. MIT Press.

The Twelve Caesars, quoted above and translated by yours truly, is available as an ebook by clicking the link below or online everywhere you expect to find books.

I have two words for you, just two words. “Fish sauce.”

I routinely cycle past one if the farms that hosts the sheep that graze the vast expanses of grassland that are the reservoirs to the south west of Heathrow Airport that are the store of water that post-treatment is the drinking water for much of west London. In the Spring the earthy stench of partially oxidised lanolin is pervasive.