"Maximus! There's a problem at the Roman villa!"

"The Roman villa!? What is it?"

"It's a big building in the countryside full of mosaics, but that's not important right now..."

With apologies to one of the finest comedy lines in cinema history, a Roman villa is, essentially, a big building in the countryside full of mosaics. The problem with trying to answer a question like 'what is a Roman villa?' is that the answer is both relatively straightforward in terms of a physical description and subtly nuanced in terms of cultural identity. What Pliny the Younger considered a 'villa' - somewhere he could loaf about all day, thinking about stuff - is not the same as a wealthy Romano-Briton might consider a 'villa' - the hub of an industrial, agricultural and monumental landscape - even if both of them could recognise that each other's complexes were identifiably villas just by wandering around in them.

Both Pliny's and the Romano-Briton's villas are expressions of power, and whilst one might be a bolt-hole in the country or a surrogate for the urban palaces crammed on the Palatine Hill in Rome (the word 'palace' comes from the buildings on the Palatine, after all), the other might be expressed as the new architectural 'meta', plugging a gap that was previously filled by the hillfort.

The term 'hillfort' is somewhat misleading, and although they obviously served some form of defensive purpose, the primary reason for a hillfort's existence appears to have been a demonstration of power and wealth. Showing off, essentially. Grand statement pieces in the landscape to let everyone else know who was top dog. Hillforts came in all sorts of dimensions to mirror the power and wealth of the individual or individuals who owned them, and the Romano-British villa can be seen as the new-fangled way of expressing the same idea. The people who owned them and called them 'home' were, therefore, not the average Romano-Briton; they were not simply Roman versions of homes, and the locals went on living in roundhouses during and after the Roman period. Even if the majority of the people who worked in them were ordinary folk and not wealthy, the villa was the fancy pad of that society's elite.

That society's elite was, naturally, a relative term and, as such, you get big hillforts and little hillforts. Some are little more than large family-oriented enclosures, and others are immense things you could fit a town into. The Roman word for 'fort' - castrum - gives us the word 'castle' in English, but this word is used to describe what are primarily Roman military sites. Other defended sites, including things like hillforts, were called castra, a word that means both 'camp' and is, confusingly, the plural of castrum. Hence, you sometimes find the term surviving in local placenames as 'castles' when there is only one such site in the local area.

It's possible then to see the villa as the precursor to the castle, but maybe not in the purely defensive meaning of the word. Castles served as everything from refuge in times of war to administrative centres, to agricultural and market hubs, to seats of power for sword-wielding local hoodlum warlords. Manor houses, if you like. Visit any grand British country house, and as well as the showy-off grandeur and hundreds of bedrooms, you'll also, more likely than not, find a whacking great big, working farm attached to the estate. They are, essentially, great big, Georgian fronted Roman villas.

Another feature of Roman forts that almost everyone is aware of is their cookie-cutter nature. With very few exceptions, Roman forts were all constructed to a set of architectural rules that make them easily identifiable in the landscape. As discussed, villas also contain features which make them relatively easy to identify and even though their cultural impact and forms of decoration might change across the empire, that they can be so readily identified as villas shows the cultural impact of Roman society.

Roman villas were characterised by a distinctive architectural style that reflected both practical needs and aesthetic considerations. The typical Roman villa was a sprawling complex that included residential quarters, agricultural facilities, and often luxurious amenities such as baths, gardens, and mosaics. The layout of a Roman villa was usually centred around a courtyard or peristyle, an open space surrounded by columns that provided light and ventilation to the surrounding rooms. This central courtyard might be adorned with fountains, statues, and lush greenery, creating a serene and visually pleasing environment for those who used their villas more as rural versions of their urban sprawls. In more agricultural settings, the courtyard might be where local produce is brought to be counted, sorted and sold.

The residential quarters of a villa were typically located in the main wing of the house, while the others housed service areas such as kitchens, storerooms, and workshops. The living spaces were often richly decorated with frescoes, mosaics, and marble floors, reflecting the wealth and status of the villa's owner. The use of hypocaust systems for underfloor heating was another common feature, particularly in the colder regions of the empire, demonstrating the Romans' advanced engineering skills (Percival, 1976).

The construction of Roman villas employed a variety of materials and techniques, depending on the region and the resources available. In Italy, for example, villas were often built using locally sourced stone, brick, and concrete, with walls covered in stucco or painted plaster. The use of concrete, in particular, allowed for the creation of large, open spaces and complex architectural forms, such as vaulted ceilings and domes (Adam, 1994).

In the provinces, the construction techniques varied according to local traditions and materials. In Britain, for example, villas were often built using timber and thatch, with stone foundations and tiled roofs. This means that the archaeological remains of such buildings are often restricted to what is left of hypocaust systems and mosaic floors. The use of local materials not only reduced construction costs but also helped the villas blend into the surrounding landscape, creating a harmonious relationship between the built environment and the natural world (Smith, 1997).

That might, on the outside, make it seem like the villas of Roman Britain were somehow less sophisticated than elsewhere in the empire, and for many years, Romano-British villas, like the art found within them, were considered rather naive. Instead, it might be better to think of the people who owned and lived in them as fully invested members of a pan-empire Roman society, particularly later in the period, who were fully aware of all the trappings of Roman culture, including mythological motifs from as far away as Africa, but who expressed their Roman identity in ways that were uniquely Romano-British. The style of the villas and the art can then be seen less as rustic and somewhat unsophisticated and more as just the locals expressing themselves in ways that were unique to them.

Nowhere is this better seen than in what might be a villa's most recognisable universal feature - the mosaic floor. Where they escape the plough, mosaics provide valuable evidence for evaluating villa life and the art scene in Roman Britain. Most of them are relatively simple, although this doesn't necessarily mean they were cheap and nasty. Minimalism is an art form in any century. More complex geometric designs and those featuring figures were also popular, and while the latter was almost certainly more time-consuming to lay and therefore more expensive, that doesn't mean that the simpler designs necessarily are the work of inferior craftsmen or customers looking to get work done on the cheap. Even a simple design can still be part of a more elaborate overall pattern.

The adoption of mosaics as home decorations is part of the trend of the Romano-British adopting particularly Roman fashions. Nothing like it was known in Britain before the Romans showed up, so this is one area where cultural exchange is totally in one direction. Having said that, although the Romano-British followed the changing face of mosaic fashion like everyone else, they also forged their own particular design niches. This sharing of ideas around the empire was probably helped by the fact that the layers of these pavements, like medieval stone masons, were peripatetic, travelling to wherever the work was available. This, of course, includes moving across the continent and bringing fashions and ideas into and out of Britain. However, there were also distinct British schools of design suggesting that craftsmen became well known for producing certain types of work to a certain standard.

This would suggest that they worked off some kind of pattern book, like a modern-day carpet salesman with a swatch full of samples (although no such book has ever been found). The salesmen would turn up with a roll of designs under one arm and a measuring device, size up the rooms, discuss which designs and figures you'd like and then discuss a price. A few days later, or 9 months if they're anything like modern-day 'craftsmen', two blokes would turn up and sit in the wagon outside for half the day drinking posca (watered-down sour wine) and complaining that they don't have the right tools and Maximus had to go 'back to the depot'. These design books must have changed as seasons and tastes changed and it's easy to imagine an excited salesman eagerly informing a client that the new designs from Gaul are in, or 'Have you seen what they're doing in Athens this year?' It gives the Romano-Britons the opportunity to share in the empire's cultural values.

Romano-British mosaics show a knowledge of Graeco-Roman mythology, just like their counterparts in Africa or Spain, say, but just as in those areas, there are some distinct local characteristics. The Romano-British have something of a penchant for rather obscure myths but don't widely follow the continental fashion for subjects like the circus and the amphitheatre, and in general, they seem to steer away from the Roman preoccupation with the rural idyll. Rome's elite saw their ancestry in their supposed Etruscan roots and the pagan, bucolic utopia of the peasant fantasy. This is clearly not how the British see their own origins, and such imagery is just reflective of a way of life the Romano-British are trying to move away from, not aspiring to get back to. Nouveau-riche Romano-British villa owners are not looking back on Roman ancestry, as they are in Italy; they are either looking forward to a new world of Roman influences or drawing on their own ancestry to express themselves as Romano-Britons.

What's interesting about mosaics in Britain is that the style that used to be dismissively referred to as 'naive' is still work of a high standard. They are not the work of unskilled craftsmen. Presumably, then, the results are not simply the 'best' that they could produce but rather work that customers are expressly demanding. Villa owners are, one might assume, flicking through the pattern books and picking these designs out, presumably because they represent a very British cultural view of their place in the wider empire.

There are some places where the absence of villas is quite noticeable and there might be a variety of reasons for this. In the north of England, near Hadrian's Wall, the villa economy is largely absent, and this might be the result of the increased military presence. All the land and the agricultural produce is going to serve the military, and subsequently, there is no room for the villa model in the economy. What this might show is that villas are the result of localised economic circumstances rather than the drivers of such an economy. Villas don't drive economic wealth, they appear as a result of it.

Elsewhere, the landscape itself might not be conducive to a villa economy. It just isn't an agricultural landscape; instead, the local population grows around much smaller and less formal population centres that still interact with the Roman economy but never get enough fuel to drive greater interaction.

Having said that, there are some areas where not only is the landscape seemingly ripe for agricultural exploitation, but the local economy would appear to be ideally suited to a villa model; there are plenty of local population centres, and everyone seems to be playing along with the Romano-British lifestyle quite happily. But there are no villas.

Areas such as Norfolk and Suffolk are today some of the best arable land in Britain, and even accounting for the fact that a lot of this land was reclaimed from its boggy nature in the post-Roman period, the relative lack of villas in that area is notable. So if the land is good enough, and the locals are compliant, and the area is wealthy enough to support a large Roman colonial settlement at Colchester, where are all the villas?

The archaeology is tricky in this respect because, whilst there's plenty of it, the agricultural impact is somewhat muddied (if you'll forgive the pun) by all that land reclamation in the medieval period and beyond. The settlements in this area tended to be on higher ground or relatively higher ground - Norfolk is pretty flat - and these survive later agricultural activity, including the dreaded ploughing. The farmland does not. So we can't tell exactly what the model was like, but the military presence is relatively light, the soil is good and, of course, no villas. So they were farming there, one assumes, but in another form.

Villas grow as a consequence of wealth rather than being parachuted into the countryside to exploit wealth. They start out small and become bigger as the owners grow in wealth and status and are less about prime land being parcelled off for exploitation. As the economy grows and shrinks, so do the villas. It's one of the reasons the villa model disappeared entirely in the post-Roman period - the land is still suitable for farming and is farmed, but the economy has moved to a different model, and the villa as an expression of wealth is no longer part of the narrative.

People are still wealthy, naturally, but they begin to express that wealth in other ways. In the Anglo-Saxon period, that might mean military might. Expressing your wealth via personal military power, especially with no Roman army around, becomes fashionable. In Medieval times, rich people built large manor houses and exploited peasant farmers. When things got really rich, they built castles. So the absence of villas in Norfolk might simply be because people are expressing their wealth in other ways than with villas.

But enough about Britain as an example and back to the villa in general. Roman villas had a profound impact on the surrounding landscape, both in terms of their physical presence and their economic activities. The construction of a villa often involved significant alterations to the natural environment, including the clearing of land for agriculture, the construction of roads and infrastructure, and the creation of gardens and water features. These changes not only transformed the physical landscape but also had a lasting impact on the local ecosystem and biodiversity (Smith, 1997).

The economic activities carried out at a villa also had a significant impact on the surrounding area. The production of crops, livestock, and other goods created a demand for labour and resources, leading to the development of local markets and trade networks. The presence of a villa could also attract other settlers and businesses, leading to the growth of nearby towns and villages (Percival, 1976).

The design and function of Roman villas varied significantly across the empire, reflecting the diverse cultural, economic, and environmental conditions of different regions. In Italy, for example, villas were often luxurious country retreats, used by the Roman elite as a place to escape the pressures of urban life and enjoy the pleasures of the countryside. These villas were typically located in scenic areas, such as the hills of Lazio or the coast of Campania, and were designed to take full advantage of the natural beauty of their surroundings (Wallace-Hadrill, 1994).

Columella, a 1st-century AD Roman writer on agriculture, provides one of the most detailed accounts of life in a working villa in Italy. In his treatise De Re Rustica (On Agriculture), Columella emphasises the importance of the villa as both a productive farm and a residence for the landowner. He describes the ideal layout of a villa, including the placement of the villa urbana (the luxurious residential quarters) and the villa rustica (the working farm buildings). Columella stresses that the villa should be self-sufficient, producing food, wine, and other goods for both the household and the market (Columella, De Re Rustica, Book 1).

Columella also provides insights into the daily life of a villa owner. He advises landowners to take an active role in managing their estates, stating that "the master's presence is the best incentive to good work" (De Re Rustica, Book 1.8). This suggests that villa owners were expected to oversee agricultural operations personally, rather than delegating all responsibilities to overseers or slaves. Columella's work also highlights the importance of slaves in villa life, as they were responsible for the bulk of the labour, from tending crops to maintaining the villa's infrastructure.

Pliny the Younger offers a contrasting perspective on villa life. In his letters, Pliny describes his villas as places of leisure and intellectual pursuit, rather than centres of agricultural production. His villa at Laurentum, for example, was a coastal retreat where he could escape the pressures of public life in Rome. Pliny writes fondly of the villa's peaceful surroundings, its proximity to the sea, and its well-appointed rooms, which included a library and a heated bath complex (Pliny the Younger, Letters, 2.17).

Pliny's letters also reveal how villas were used for social and cultural activities. He describes hosting friends and colleagues at his villas, where they would engage in philosophical discussions, read literature, and enjoy the natural beauty of the countryside. For Pliny, the villa was not just a residence but a space for intellectual and social enrichment. His descriptions highlight the dual role of villas as both private retreats and venues for displaying one's cultural sophistication and hospitality.

For the elite, villas were multifunctional spaces that served as residences, economic centres, and venues for social and cultural activities. The daily routine of a villa owner might include overseeing agricultural operations, hosting guests, and engaging in intellectual pursuits. Slaves and servants played a crucial role in maintaining the villa and supporting the lifestyle of its owner, performing tasks ranging from farming to cooking and cleaning.

The villa was also a place of leisure and relaxation, particularly for those who owned multiple properties and could retreat to the countryside during the summer months. Pliny's descriptions of his villas as peaceful havens reflect the Roman elite's appreciation for the natural beauty of the countryside and their desire to escape the noise and chaos of urban life.

The inhabitants of a Roman villa were part of a clearly defined social hierarchy. At the top was the dominus (master), who owned the villa and oversaw its operations. The dominus might be a senator, equestrian, or wealthy landowner, and his family would also reside in the villa. Below the dominus were the vilicus (estate manager) and the villica (housekeeper), who were often slaves or freedmen responsible for managing the day-to-day affairs of the villa.

The majority of the villa's inhabitants were slaves or, in the provinces, manual workers who performed a wide range of tasks, from agricultural labour to domestic service. Columella provides detailed instructions on how slaves should be managed, emphasising the importance of fair treatment and proper incentives to ensure their productivity (De Re Rustica, Book 1.8).

It's easy to think of the villa as something akin to a Roman fort - a big, universally recognised rubber stamping of Roman identity on a local population. But this is misleading. Instead, it might be better to think of the Roman villa as the results of one of the prime motivations for Roman expansion - the exploitation of resources - but also, more intriguingly, as catalysts for the locals to express themselves as, eventually, fully paid-up members of the Roman world.

There was always a trope running through Roman society of Rome as the world and the world as Rome and in terms of expressed culture, the more the empire grew to absorb other identities, so those identities also became part of a greater whole. The villas of Roman Britian, then, were not simply the results of the locals being brow-beaten into adopting Roman ways, but opportunities for the locals to define what it meant to be a Roman.

References and Further Reading

Adam, J. P. (1994). Roman Building: Materials and Techniques. Routledge.

Columella, L. J. M. (1st century AD). De Re Rustica (On Agriculture).

Ellis, S. P. (2000). Roman Housing. Duckworth.

Percival, J. (1976). The Roman Villa: A Historical Introduction. Batsford.

Pliny the Younger. (early 2nd century AD). Letters.

Smith, J. T. (1997). Roman Villas: A Study in Architecture and Society. Cambridge University Press.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. (1994). Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton University Press.

Columella, L. J. M. (1941). De Re Rustica (E. S. Forster & E. H. Heffner, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Pliny the Younger. (1969). Letters (B. Radice, Trans.). Penguin Books.

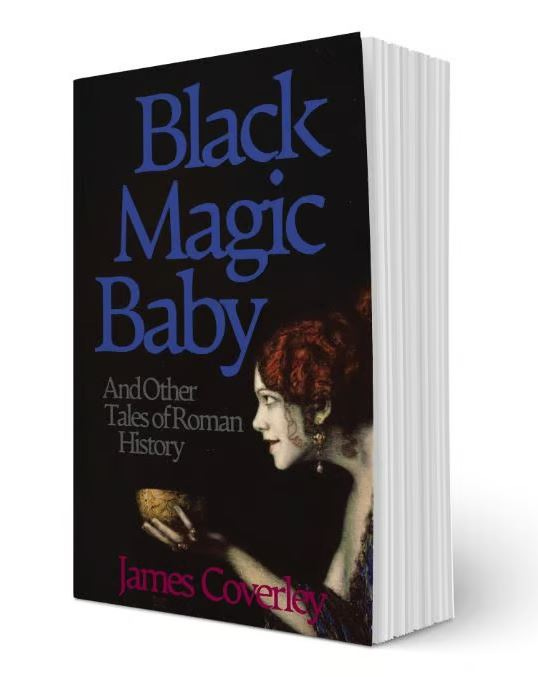

If you enjoyed this article, you’ll love my latest book, Black Magic Baby, crammed full of interesting answers to all the questions you ever had about Roman history that will keep you turning pages long into the night. They make rather cool gifts for nerdy types who go mad for that sort of thing!

Print or ebook versions are available at the link below!

Great post.

Do we see any examples of ideology and snobbishness trumping climate/physics in Roman elite building practices?

For instance, the Romans didn't like pants, but as the Romans went north, they gave in and adopted pants because climate is a thing.

In the villa context you mention local materials and heated floors. But were these villas actually well adapted to cold climates, or buildings adapted to the southern Mediterranean being jury-rigged to serve in England because that's what culture demanded?

Sod houses are well adapted to Scandinavia, for instance. Is the villa equally well adapted, or just posturing?

Two changes between the pre-industrial world into the modern world are the separation of workplace and residence, and the separation of production and consumption. The co-mingling of production and consumption is evident in the elite houses of Pompeii according to Wallace-Hadrill. I am only familiar with a few literary examples of Italian villas. It appears that Italian villas and Romano-British villas combined these functions, too.