I don't really like cows. I'm not frightened of them; I just don't like them. People think that not liking cows is a bit weird - after all, they can look quite cute, especially the big doe-eyed, Jersey types - but I don't like the buggers. Mostly, it must be said, because we had cows when I was growing up, and for a long while, lured by the promise of a shiny new BMX that never arrived, it was my job to get up at 4 in the morning and milk the bastards. Sometimes in winter and sometimes, as was frequent in wild West Wales in the 1980s, when the power had gone off, and it had to be done by hand. In freezing temperatures. And then one of them would kick the bucket over. And then shit in it.

So I don't like cows.

Cows are essentially human inventions, modern versions of ancient, gigantic wild aurochs that our ancestors tamed. Having just tamed wild dogs, which are awesome, they needed to tame something really annoying to balance it out a bit. So they picked cows.

Where there are cows, there are also baby cows, an unfortunate by-product of an unfortunate industry, and whilst these ultra-cute little blighters are infinitely less annoying, they are ultimately destined to meet the same fate as all cows, namely that someone, or something, will eat them.

Back in those days, for a small extra fee, the man from the slaughterhouse would do home visits, and a sad little procession of our freshly hand-reared, super-cute baby cows would be led out into the yard, blinking into the sunshine, where they would be 'processed' with alarming speed, albeit with impeccable professionalism. A short while later, a line of prepared carcasses would be hanging up in the barn, ready for their destination. The slaughterman would take a few; some would go into our freezer, and the rest would enter the food chain - all very Silence of the Lambs.

Such is the fate of cows. It's not a great life, to be honest.

Drive around the lavender-scented fields of Provence, where I spent a few happy years, and you'll occasionally come across a small, dusty paddock dotted with a few dozen hulking, jet-black bulls, their tails swinging lazily in the shade of an olive tree. What you're looking at are, more than likely, fighting bulls because down there, you're in bull-fighting territory. It's hard to associate the terrified, angry animals you see in the arenas with these handsome, laconic animals, and, to be fair, not all of them will make it that far. They only take the most 'likely' for the gore of the fight. Those who aren't selected are simply 'processed' into food, just as the sad little calves in Wales are.

To be honest, the ones in the arena are also processed in the exact same way. Regular readers will be aware of my little foray into the fighting arena, so I won't go over it again, but after the day's work, all the arena workers met up in a packed subterranean restaurant, jostling glasses full of blood-red wine and great chunks of rare beef cut straight from the animals we'd just watched being tormented.

Such is the fate of cows. It's not a great life, to be honest, but it's marginally better than that of most other cows, at least until the last ten minutes of it.

I don't like cows or eat them.

The scene of lazy bulls swishing their tails among the olives, hiding from the searing Provencal sun, only to be dragged into a great stone arena, tortured and then eaten, is one that was as real in 1994, when I was involved in it as it had been for most of the previous 2,000 years, of course. It's a cow's life, one might say.

Obviously, then, the Romans could simply have rounded up some bulls from the local paddocks for their arena shows, just as oak-gnarled Provencal men in blue overalls do today. But Romans had all manner of creatures for the arena, not just bulls. Lions, obviously, dogs, bears, onagers (wild mules), flamingoes, hippos, elephants, tigers..... But where did they get them all from?

Beyond the gladiatorial contests that captivated crowds, the arena was also home to spectacular displays of animal combat, exotic hunts, and executions involving wild beasts. These spectacles—collectively referred to as venationes—relied on a continuous influx of animals from across the empire and beyond.

The variety of animals employed in the arena was immense and drew heavily on Rome’s imperial reach. Literary sources offer a remarkable inventory. According to Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia, VIII.65), the Romans exhibited a wide range of animals, including elephants, tigers, leopards, lions, panthers, crocodiles, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, and a diverse array of birds and sea creatures. Martial (Liber Spectaculorum, 1, 17, 23) celebrates panthers, bears, and wild boars featured in arena hunts. Cassius Dio (LXVI.25) records the exhibition of a giraffe in Rome, while Suetonius notes the display of "sea creatures" during Augustus' naumachia (Suetonius, Divus Augustus 43.4), suggesting that aquatic spectacles may have included marine animals.

More mundane creatures also had their place. Dogs were frequently used to bait larger beasts or participate in staged hunts, and mules were used for logistics and comic performances. Birds, particularly ostriches and cranes, were shown off as curiosities or used for target practice. The inclusion of monkeys and baboons is attested by mosaic representations and sculptures, as well as their known importation for private collections (Toynbee, 1973, p. 105).

Crucially, venatores—professional animal fighters—were responsible for these displays. They differed from gladiators, though the two roles could overlap. Epigraphic evidence from tombstones, such as the inscription for Carpophorus (CIL VI.10050), attests to the bravery of men who battled multiple wild beasts in a single day. Their presence was as essential to the performance as the animals themselves.

The literature of the Roman world provides vivid testimony to the scope and ambition of these spectacles. Martial's Liber Spectaculorum, written to commemorate the inaugural games of the Colosseum in AD 80 under Titus, describes scenes of hunting, combat, and exotic wonder. In poem 7, he refers to a rhinoceros fighting a bull, and in poem 21, to lions springing upon men armed with nothing but javelins. These were not merely shows of dominance but performances crafted to astonish and awe.

Suetonius documents numerous imperial spectacles featuring animals. Augustus staged wild beast hunts in both the Forum and the Circus Maximus, with as many as 3,500 animals slain in a single event (Divus Augustus 43). Caligula is said to have had animals killed during intermissions for variety (Caligula 18), while Domitian reportedly organised daily beast hunts and night-time shows involving torch-lit performances (Suetonius, Domitian 4). Cassius Dio (LXI.9) recounts an incident in which an elephant kneels before the emperor in supplication, an image that highlights the performative taming of the wild as a manifestation of imperial power.

Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia (Book VIII) provides essential zoological and anecdotal insight into many of these animals. Although some descriptions are exaggerated or inaccurate, his work remains invaluable as a contemporary account of Roman interest in the exotic. His listing of beasts captured or bred in various provinces offers clues to the geographic sourcing of animals.

Material evidence confirms the logistical underpinnings of the animal trade. Amphitheatres throughout the empire featured subterranean systems—hypogea—that housed animals prior to their release. The Colosseum's hypogeum, added under Domitian, included elevators and cages for lifting animals into the arena. Inscriptions, such as CIL X.1643 from Capua, mention officials responsible for managing animal hunts (curatores venationum).

Inscriptions from North Africa reveal that cities like Leptis Magna and Carthage maintained facilities for holding animals before shipment. A Punic inscription from Kerkouane details an offering to a deity for a safe sea passage of wild animals, suggesting both religious and practical dimensions of the enterprise (Ben Abed, 1998, p. 211). In Italy, ship remains from Portus and Ostia bear graffiti and cargo markings related to animal consignments (White, 2012, p. 287).

Osteological finds also support the scale and variety of animal use. Excavations in Pompeii have uncovered remains of big cats and deer near the amphitheatre (Fröhlich, 1991), and bone fragments found in the Colosseum itself point to lions, bears, and ostriches (Toynbee, 1973, p. 110). Together, these remains provide physical confirmation of the animals recorded in literary sources.

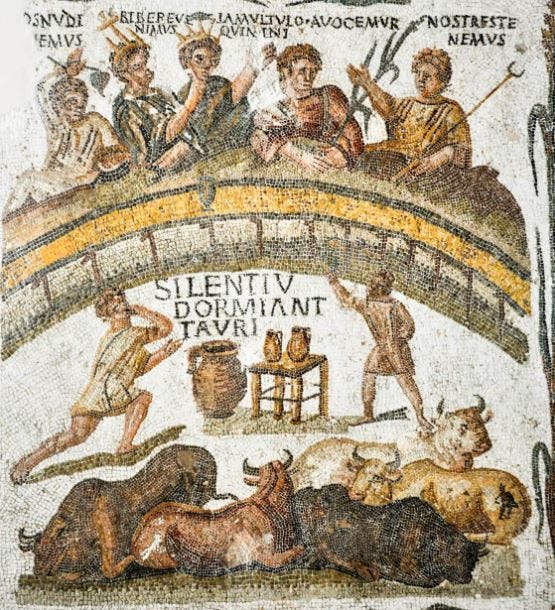

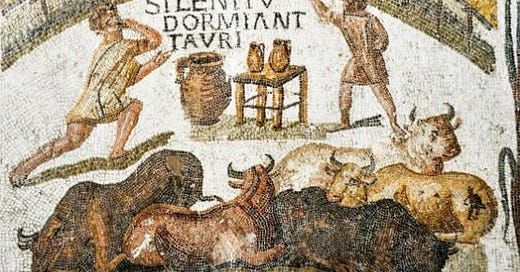

North Africa was the primary supplier of exotic animals to Rome. Lions and leopards were abundant in the regions of Numidia and Mauretania, now parts of Algeria and Morocco. Roman mosaics from locales such as El Djem and Zliten depict scenes of animal trapping, reinforcing the region's role in the supply chain. Carthage, a key imperial port, was a transit hub for animals bound for Rome. Epigraphic evidence from Lepcis Magna refers to venationes arranged by local elites, further affirming North Africa's centrality (Barker, 2002, p. 157).

Elephants, initially from North Africa, were later imported from sub-Saharan regions or India, particularly as the North African elephant population declined. Pliny (NH VIII.6) notes that the supply of elephants became increasingly difficult, indicating the pressures exerted by Roman demand.

India and the East were sources of rare and high-value animals such as tigers and rhinoceroses. Augustus is said to have exhibited a rhinoceros in Rome, according to Strabo (Geography, XVI.4.16), and tigers were first introduced during the reign of Augustus, as noted by Martial (Spect. 8). These animals were acquired through diplomatic gifts or captured during eastern campaigns. The Parthian and later Sasanian spheres facilitated indirect access through intermediaries, and Roman contact with India via the Red Sea trade allowed for sporadic imports.

The northern provinces contributed animals such as bears, deer, and wild boars. Germania and the Balkans were principal sources. Tacitus (Annals I.61) remarks on the ferocity of Germanic bears, and bones found at amphitheatres in Vindobona (modern Vienna) and Augusta Treverorum (Trier) confirm their use. Gaul supplied bulls and boars, and inscriptions from Lugdunum (Lyon) refer to venationes staged for civic festivals.

Capture methods ranged from netting and pit-trapping to baiting and spear hunting. Scenes in Roman mosaics and reliefs show teams of hunters using spears and nets to subdue animals. Once captured, beasts were kept in temporary enclosures known as vivaria. Varro (De Re Rustica III.13) and Columella (VIII.15) mention vivaria used to store game animals.

Captive breeding appears to have been rare for exotic predators such as lions and leopards, largely due to the animals' extensive space, dietary, and behavioural needs. However, certain more common or manageable animals were bred in captivity. Bulls, especially for ritual and arena purposes, were likely bred locally or on designated estates. The breeding of bulls was standard in both agricultural and religious contexts, and estates producing taurobolia (bull sacrifices) likely supplied animals for arena combat as well.

Similarly, onagers (wild asses), valued for their speed and tenacity, were sometimes caught in the wild but could also be bred in controlled environments. Columella's writings on livestock management suggest that Romans were familiar with techniques for maintaining healthy herds of equids, including crossbreeding and enclosure-based husbandry.

Dogs, too, were extensively bred within the empire, particularly for roles in hunting, guarding, and performance. The canes Pannonici (Pannonian dogs), mentioned in military and civilian contexts, were likely bred for strength and resilience. Kennels operated under both private estates and public contracts, ensuring a regular supply for arena events.

Birds such as cranes and ostriches were also known to be kept and possibly bred in semi-captive conditions for display or hunting exhibitions. Ostriches, though imported, were sometimes maintained in domestic aviaria or enclosed preserves, as suggested by archaeological finds and Roman descriptions of luxury gardens.

Transporting animals required an immense imperial infrastructure. Animals were moved overland by cart or driven in herds, then shipped from provincial ports to Rome. Specialised vessels are attested by descriptions in Lucian (De Domo) and hinted at by depictions on mosaics showing caged animals on boats.

At sea, animals were contained in wooden cages reinforced with iron. The dangers of transport were considerable—Cassius Dio (LVI.27) records animals dying en route or escaping during unloading. Portus and Ostia had dedicated docking areas and warehouses to accommodate animal traffic, with some structures interpreted as navalia for animal-bearing vessels (Keay & Millett, 2005).

Once in Rome, animals were brought to the Colosseum via the Tiber and stored in the vivarium—a holding pen likely located near the Colosseum or on the Caelian Hill (Richardson, 1992, p. 426). From there, they were marched to the arena on the day of the event.

While Rome's Colosseum remains the most iconic venue, amphitheatres across the empire held their own spectacles. Carthage, Capua, and Nîmes all featured extensive amphitheatres with hypogea. Inscriptions from Augusta Emerita (Mérida) and Londinium (London) show evidence of animal games funded by local elites.

Unlike in Rome, provincial spectacles were often smaller in scale but retained their exoticism. Lions are attested in Britain, and bear pits were common in frontier regions. These events reinforced Roman identity by mirroring the centre's grandeur on a local stage, often funded as munera by magistrates.

The procurement of animals for the Colosseum and other Roman amphitheatres was a feat of imperial logistics sustained by conquest, trade, and local initiative. Drawing from the empire's vast territories—from African savannahs to Asian jungles and European forests—Rome curated an animal menagerie unmatched in scale and diversity. This system depended on a web of hunters, handlers, sailors, and administrators, supported by infrastructure built to accommodate a uniquely Roman appetite for spectacle. While most animals were taken from the wild, the Romans also developed selective breeding programs for certain species, demonstrating a layered and adaptive approach to animal supply. Far from incidental, these animals served as emblems of Rome's reach and dominion, their presence in the arena a living testament to the empire's global ambitions.

References and Further Reading.

Barker, G. (2002). The archaeology of Roman North Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Ben Abed, A. (1998). Carthage: The Roman metropolis. Museum With No Frontiers.

Columella. (1941). On Agriculture (H. B. Ash, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Fröhlich, T. (1991). Lararia in Pompeii: Household shrines and Roman domestic religion. L’Erma di Bretschneider.

Keay, S., & Millett, M. (2005). Portus: An archaeological survey of the port of Imperial Rome. British School at Rome.

Lucian. (1913). De Domo (A. M. Harmon, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Martial. (2006). Spectacles (D. R. Shackleton Bailey, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Pliny the Elder. (1938). Natural History (H. Rackham, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Richardson, L. (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Strabo. (1924). Geography (H. L. Jones, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Suetonius. (2025). The Twelve Caesars (J. Coverley, Trans.).

Tacitus. (1942). The Annals (A. J. Church & W. J. Brodribb, Trans.). Random House.

Toynbee, J. M. C. (1973). Animals in Roman Life and Art. Thames & Hudson.

White, R. (2012). Art, artefacts and chronology in classical archaeology. Cambridge University Press.

How did the presence of animals impact how Romans used city streets? In addition to the arena, were there other uses of exotic animals in Rome?