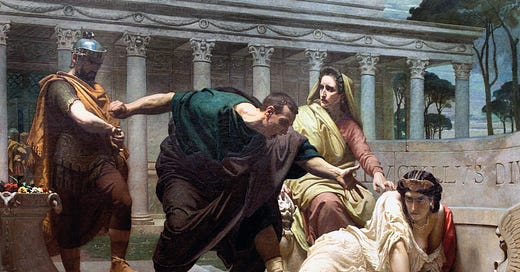

As you could probably expect, the night-shadowed streets of ancient Rome were not exactly the safest places to wander, arm-in-arm with a loved one, taking in the soft evening air as one meandered gently home after an evening meal. There was always some rough-capped brigand and his bunch of swarthy German companions at hand to beat you senseless, rob you of your finest and throw you in a sewer. If it wasn't, the same pack of reprobates might break into your store, loot everything you own and then, without so much as a hoot of shame, set up a market stall the next day, selling all your stuff. It was even worse when it turned out that the leader of these brutish miscreants was none other than the emperor himself, Nero (of course), and there was absolutely sod-all you could do about it.

Suetonius provides a vivid account of Nero's nocturnal escapades:

"He would roam the streets at night, disguised as a slave, and engage in brawls and riots. He would attack people returning from dinners, stab them if they resisted, and throw their bodies into the sewers. He would also break into shops, plunder them, and set up a market in the palace where he sold the stolen goods."

(The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Nero, 26)

According to Tacitus (Annals, 13.25), his plan was simple. He'd start the fight himself, but being a great big baby, he would then pull back as soon as the poor unfortunate started to resist and let his Batavian bodyguard, also in disguise, beat the victim to a pulp. The problem was that word soon got around that the leader of this violent street gang was Nero himself, and so the victims were far too scared to fight back or to allow their own bodyguards to step in to protect them, lest they find themselves in the unfortunate position of administering a stiff right to the nose of some street goon, only to then find out they had just smacked Nero in the chops. Chaos promptly ensued as hundreds of similarly disguised street gangs took to the night, robbing and plundering with impunity, safe in the knowledge that a terrified populace was so scared of fighting back that they would simply throw all their valuables at anyone who even looked vaguely menacing and then run. Within weeks, the whole city was in absolute uproar, and it took the praetorian guard, with regular night patrols, to restore some sense of order.

Of course, the praetorians were a military force and (nominally at least) the emperor's personal legion, but in this respect, they acted with the same sort of power as a modern police force. Which brings us, rather neatly, to today's question—did ancient Rome have a police force?

Ancient Rome, renowned for its legal and administrative innovations, developed a sophisticated system for maintaining public order. However, the concept of a "police force" as we understand it today—a professional, centralised body dedicated to crime prevention, investigation, and public safety—did not exist in the same form. Instead, the Romans relied on a combination of military units, civilian watchmen, and elite guards to enforce laws and protect citizens. This essay examines the roles of key Roman institutions, such as the vigiles, urban cohorts, and praetorian guard, and evaluates how they functioned within the broader context of Roman society. By comparing Roman approaches to modern policing, we can better understand the evolution of law enforcement and the enduring legacy of Roman practices.

To assess whether the Romans had a police force, we should first define what constitutes a police force in a modern context. Modern policing is characterised by a professional civilian body with a mandate to prevent crime, maintain public order, and enforce laws. Police officers are typically trained, salaried, and operate under a centralised authority, such as a government or municipal agency. They have specific powers, including the authority to arrest, investigate, and use force when necessary.

In contrast, Roman law enforcement was decentralised and multifaceted. The Romans did not have a single, unified police force but rather a collection of institutions with overlapping responsibilities. These institutions were often military in nature, reflecting the close relationship between the army and public administration in Roman society. While some units, like the vigiles, had duties akin to modern firefighters and night watchmen, others, such as the urban cohorts, functioned as a hybrid of police and military forces. The praetorian guard, meanwhile, was primarily an elite military unit but occasionally assumed law enforcement roles, particularly in protecting the emperor and maintaining order in the capital.

The key difference lies in the professionalisation and specialisation of modern policing. Roman law enforcement was not a distinct career path but rather an extension of military or civic duties. Moreover, the Romans relied heavily on social hierarchies and citizen participation to maintain order, which contrasts with the more formalised and egalitarian approach of modern systems.

The vigiles were one of the most recognisable institutions involved in maintaining public order in ancient Rome. Established by Emperor Augustus in AD 6, the vigiles were initially tasked with firefighting, a critical responsibility in a city prone to devastating fires due to its dense wooden structures. However, their duties expanded to include patrolling the streets at night, apprehending thieves, and ensuring general safety. Composed primarily of freedmen, the vigiles were organised into seven cohorts, each responsible for two of Rome's fourteen administrative regions.

While the vigiles performed functions similar to modern police, such as patrolling and apprehending criminals, they were not a dedicated law enforcement agency. Their primary focus remained fire prevention and control, and their authority was limited compared to modern police forces. Nevertheless, their presence contributed significantly to public safety in Rome.

The urban cohorts (cohortes urbanae) were another key institution in Roman law enforcement. Created by Augustus around the same time as the vigiles, the urban cohorts were a military force tasked with maintaining order in the city of Rome. Unlike the vigiles, who were primarily civilians, the urban cohorts were soldiers under the command of the urban prefect (praefectus urbi). Their duties included suppressing riots, protecting public buildings, and enforcing the emperor's decrees.

The urban cohorts were more akin to a modern police force than the vigiles, as they had a broader mandate to maintain public order and enforce laws. However, their military nature and close ties to the emperor's authority set them apart from civilian police forces. Their role was as much about protecting the regime as it was about ensuring public safety.

The praetorian guard was the most elite military unit in ancient Rome, tasked with protecting the emperor and his family. While their primary role was military, they occasionally assumed law enforcement duties, particularly in times of crisis. For example, they were involved in quelling riots and arresting political dissidents. However, their involvement in policing was sporadic and secondary to their military functions.

The praetorian guard's dual role as both protectors of the emperor and enforcers of public order highlights the blurred lines between military and law enforcement in ancient Rome. Unlike modern police forces, which are civilian institutions, the praetorian guard was deeply embedded in the political and military structures of the Roman state.

Roman law enforcement relied on a combination of preventive measures, investigative techniques, and harsh punishments to maintain order. Preventive measures included the presence of the vigiles and urban cohorts in public spaces, as well as the use of informants to gather intelligence on potential threats. The Romans also employed a system of public shaming and fines to deter criminal behaviour.

Investigations were often conducted by magistrates or officials appointed for specific cases. While the Romans did not have a formal detective force, they relied on witnesses, confessions, and circumstantial evidence to solve crimes. Punishments were severe and designed to serve as a deterrent. Common penalties included fines, exile, forced labour, and execution. Crucifixion, for example, was a particularly brutal form of punishment reserved for slaves and non-citizens.

The Roman approach to crime prevention and punishment was shaped by the belief that harsh penalties would deter criminal behaviour. However, this system was often arbitrary and heavily influenced by social status. Wealthy citizens could often avoid punishment through bribery or political connections, while slaves and the poor faced the full brunt of the law.

Roman law enforcement was deeply influenced by the societal and cultural norms of the time. The rigid class distinctions in Roman society meant that policing was often biased in favour of the elite. Slaves, who made up a significant portion of the population, were subject to harsher treatment and had limited legal protections. The Roman concept of patria potestas (paternal power) also meant that heads of households had significant authority over their families, reducing the need for state intervention in domestic matters.

Citizen participation played a crucial role in maintaining order. Wealthy citizens were expected to contribute to public safety by funding the vigiles or serving as magistrates. This reliance on private initiative and social hierarchies contrasts sharply with modern policing, which is based on the principle of equal protection under the law.

The Roman emphasis on honour and reputation also influenced law enforcement. Public shaming and fines were often used to punish offenders, reflecting the importance of social standing in Roman culture. This approach was effective in a society where reputation was closely tied to one's identity and status.

While Roman law enforcement was effective in maintaining order within the constraints of its time, it had significant limitations compared to modern systems. The lack of a centralised, professional police force meant that law enforcement was often reactive rather than proactive. The reliance on military units and citizen participation also made the system vulnerable to corruption and abuse of power.

Modern policing, by contrast, is based on the principles of accountability, transparency, and equal protection. Police officers are trained professionals who operate under strict legal guidelines, and their actions are subject to oversight by independent bodies. While modern systems are not without flaws, they represent a significant evolution from the Roman approach.

Another key difference is the role of technology in modern policing. Advances in forensic science, surveillance, and communication have transformed the way crimes are investigated and prevented. The Romans, lacking such tools, relied on more rudimentary methods, such as eyewitness testimony and physical evidence.

That's not to say that investigations into events such as sudden and unexpected deaths to try and establish a series of events leading up to a cause didn't occur. A particularly tragic tale comes from Egypt, recorded on a papyrus, that tells of the sudden death of a salve boy who fell from a window whilst the poor little chap was eagerly trying to lean out to get a view of some travelling minstrels that had come to town:

"… At a late hour of yesterday the sixth while there was a festival in Senepta and cymbal-players were giving the performance as custom has it in front of the house of my son-in-law, Ploution the son of Aristodemos, his slave Epaphroditos aged about 8 years, wishing to lean over from the flat-roof of the said house to see the cymbal-players, fell and was killed. Presenting therefore this request I ask, if it please you, that you dispatch one of your assistants to Senepta so that the body of Epaphroditos may receive the suitable layout out and burial. …"

(P.Oxy. III 475)

A sad story, but the start of the Papyrus has an interesting few lines:

"Hierax, strategus of the Oxyrhynchite nome, to Claudius Serenus, assistant. A copy of the application which has been presented to me by Leonides also called Serenus is herewith sent to you. Take a public physician and view the dead body referred to, and having delivered it over for burial make a report in writing. Signed by me."

So Hierax has asked Claudius Serenus to take a doctor with him to view the body and write a report to establish how the boy died, presumably with the intention of ascertaining who, if anyone, was to blame. There could be a number of reasons for this. By the time this papyrus was written (AD 182), masters couldn't simply have their own slaves killed, so establishing that this was an accident might be important. It could also be that the master needs to record the boy as being dead so he doesn't have to pay any taxes on him. Perhaps someone had accused the master of having the boy thrown from the window.

Either way, what we are seeing is the beginning of a forensic investigation into the excited little chap's sad death.

In conclusion, while the Romans did not have a police force in the modern sense, they developed a sophisticated system of law enforcement that reflected the needs and values of their society. Institutions like the vigiles, urban cohorts, and praetorian guard played crucial roles in maintaining public order, but their functions were often intertwined with military and civic duties. The Roman approach to policing was shaped by societal hierarchies, cultural norms, and the limitations of their time.

References

Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome. Translated by Michael Grant, Penguin Classics, 1996.

Fuhrmann, Christopher J. Policing the Roman Empire: Soldiers, Administration, and Public Order. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Nippel, Wilfried. Public Order in Ancient Rome. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Robinson, O.F. Ancient Rome: City Planning and Administration. Routledge, 1994.

Southern, Pat. The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Suetonius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars.

Thanks for reading! If you’re stuck for a gift for a lost loved one, or for someone you hate, or if you have a table with a wonky leg that would benefit from the support of 341 pages of Roman History, my new book “The Compendium of Roman History” is available on Amazon or direct from IngramSpark. Please check it out by clicking the link below!

Thanks very much for your writings.

It’s always seemed odd to me that the Romans didn’t have the equivalent of a DPP or a DA, but rather abrogated the prosecutorial function to private citizens (like Cicero).